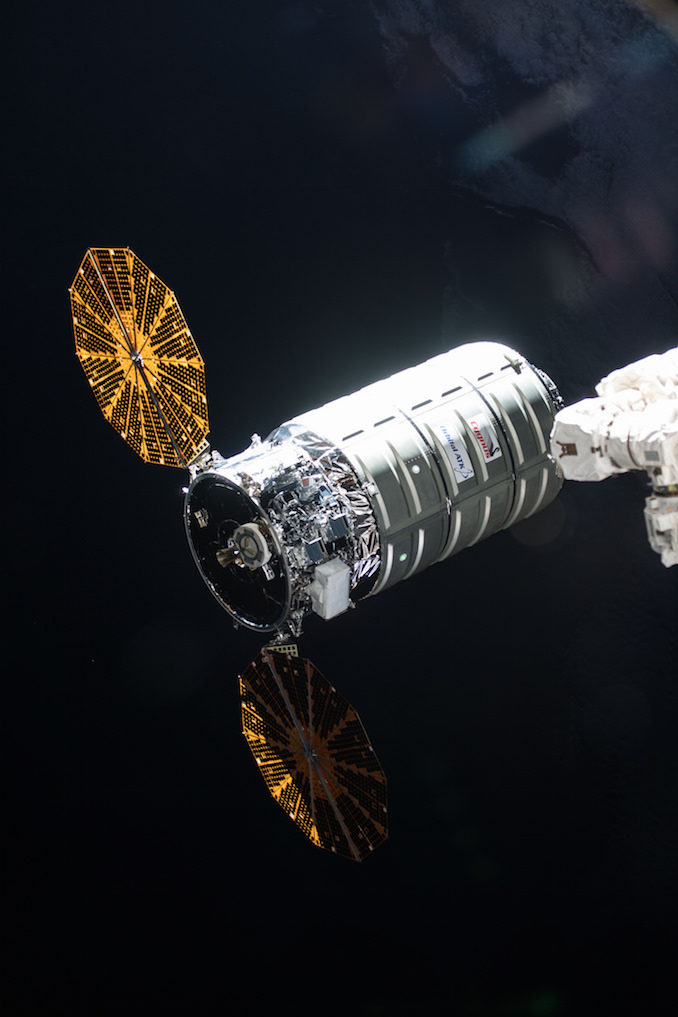

A commercial Northrop Grumman Cygnus supply ship berthed at the International Space Station fired its main engine for 50 seconds Tuesday in a test of the spacecraft’s ability to reboost, and possibly eventually deorbit, the massive research outpost.

Ground controllers at Northrop Grumman’s mission operations center in Dulles, Virginia, uplinked commands for the Cygnus spacecraft, attached to the space station’s Unity module, to ignite its main engine at 4:25 p.m. EDT (2025 GMT) Tuesday.

Before the brief reboost burn, engineers at NASA’s mission control center in Houston commanded the space station to re-orient itself to prepare for the Cygnus engine firing, pointing the cargo craft’s thruster along the station’s direction of travel in orbit more than 250 miles (400 kilometers) above Earth.

The Cygnus spacecraft’s BT-4 main engine, supplied by IHI Aerospace of Japan, fired for 50 seconds Tuesday. The engine produces around 100 pounds of thrust, and the maneuver raised the orbit of the roughly 450-ton space station by 295 feet (90 meters).

Frank DeMauro, vice president and general manager of Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems’ advanced programs division, said the maneuver went according to plan Tuesday.

“It’s been a good day,” DeMauro said in an interview with Spaceflight Now after the reboost test. “Today, all told, seemed to go very well. NASA was happy with the maneuver, and we certainly were (pleased) with the performance of the spacecraft.

“The spacecraft performed exactly as we expected,” DeMauro said. “We had an on-time ignition of the engine, and an on-time shutdown.”

Tuesday’s thruster firing was a demonstration of the Cygnus spacecraft’s orbit-raising capability before NASA and Northrop Grumman use the Cygnus main engine for longer, more significant reboosts on future missions, which could launch with extra propellant for the job.

It was the first time a U.S. spacecraft has raised the space station’s orbit since the retirement of the space shuttle.

NASA now has commercial resupply contracts with Northrop Grumman, formerly Orbital ATK, and SpaceX to carry cargo to and from the space station. Neither company’s spacecraft had tried a reboost maneuver at the space station until Tuesday.

Russian Progress cargo freighters, and the propulsion system on the space station’s Russian Zvezda service module, have conducted nearly all of the research lab’s orbital maneuvers since the end of the space shuttle program, with the exception of a few reboosts by the European Space Agency’s now-retired Automated Transfer Vehicle. Russian mission controllers typically plan several reboost maneuvers per year to counteract the effects of atmospheric drag, which gradually pulls the space station closer to Earth.

Emergency orbit adjustments are also sometimes needed to move the space station out of the way of space junk.

DeMauro said NASA and Northrop Grumman managers began discussing the Cygnus spacecraft’s reboost capability last year.

“Now that we were successful today, we hope that we can look toward performing this service in the future, on future missions, and be part of the system that raises the station’s orbit, as they do periodically,” DeMauro said Tuesday.

Using the Cygnus spacecraft for reboosts “definitely opens up options for us in the future,” said Kirk Shireman, NASA’s space station program manager, in a press briefing after the Cygnus mission’s launch May 21 from Wallops Island, Virginia.

Future Cygnus spacecraft could also be used to lower the station’s orbit, helping guide it toward a controlled, destructive re-entry over the remote Pacific Ocean when officials decided to retire the science outpost. The Trump administration has proposed to end direct federal funding for the station in 2025 as NASA turns its attention to deep space exploration, but the research complex could continue flying under commercial management, or under the current government-run international partnership if Congress balks at the White House plan.

“We’ll continue to have to reboost … and at the end of life, we’ll have to deboost the station, and of course, you have to do that very carefully,” Shireman said. “It’s a very large station, and we want to put it in at a specific place over the planet. We’ll need a lot of capability at that time as well.”

Up to now, Russia has been charged with deorbiting the station, overseeing a plan that would include the launch of multiple robotic Progress freighters in succession to bring down the complex.

“The (Cygnus) spacecraft, as it’s currently configured, is really well-suited for the orbit-raising,” DeMauro said. “For deorbit, we’d probably have to modify the spacecraft a little bit, maybe add some more thrust, and we could do that by adding more engines. We look at this (test) today as a stepping stone to orbit-raising, and that would be a stepping stone toward the eventual future deorbit of the ISS.”

Shireman said in May that officials do not plan to use SpaceX’s Dragon cargo capsule for reboosts.

“The reason is more the way the Dragon is configured,” Shireman said. “It returns (to Earth), so it carries some extra mass up that Cygnus doesn’t have to, and it has the trunk. Really, it’s limited by the amount of fuel.”

Dragon spaceships return to Earth with parachute-assisted splashdowns in the Pacific Ocean, bringing home equipment and research samples. The Cygnus cargo ships burn up on re-entry, and NASA uses them to dispose of trash.

An upgraded version of the Dragon spacecraft outfitted to carry astronauts will dock with a different port on the space station, a position that could better allow the next-generation crew craft to conduct orbit-raising burns. But Shireman said he expects Cygnus missions to do more reboosts going forward.

“Cygnus has the capability relatively easily,” Shireman said. “We could add on some capability to actually take a lot more propellant up to space station, and do much larger reboosts with Cygnus. I think that’s the path we’re looking at for right now.”

The current Cygnus mission, known as OA-9, is the ninth operational Cygnus resupply flight to the International Space Station, including one spacecraft lost in a launch failure. Future missions will be renamed after Northrop Grumman’s acquisition of Orbital ATK last month, with the next Cygnus flight slated for November likely to be called NG-10.

The Cygnus spacecraft arrived at the station May 24 — three days after launching on an Antares rocket from Virginia — and delivered 7,205 pounds (3,268 kilograms) provisions, experiments and other hardware. Astronauts have unpacked the craft’s pressurized compartment and replaced the cargo with trash in anticipation of the supply ship’s departure Sunday.

Release of the Cygnus spacecraft from the station’s robotic arm is planned at 7:35 a.m. EDT (1135 GMT) Sunday, and the cargo craft will raise its orbit later Sunday for deployment of six CubeSats.

Northrop Grumman’s control team plans to conduct several more tests of the spacecraft later this month before its scheduled re-entry July 30 over the South Pacific Ocean.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.