An independent panel has informed NASA that the James Webb Space Telescope will not be ready for launch until March 2021, and Congress will have to reauthorize the long-delayed, over-budget mission after breaching an $8 billion cost cap, officials said Wednesday.

Blunders made by Webb’s manufacturing and test team at Northrop Grumman, the mission’s prime contractor, are largely responsible for the launch delay, according to Thomas Young, a former Lockheed Martin executive and NASA program manager who chaired the review board examining the mission’s development.

“We’re all disappointed that the culmination of Webb, and its launch, is taking longer than expected, but we’re creating something new here,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine in a video message addressing Wednesday’s announcement. “We’re dealing with cutting edge technology to perform an unprecedented mission, and I know that our teams are working hard and will successfully overcome the challenges.

“In space, we always have to look at the long term, and sometimes the complexities of our missions don’t come together as soon as we wish, but we learn, we move ahead, and ultimately we succeed,” Bridenstine said. “We will get there with Webb … I assure you that in the end, the Webb telescope will be worth it.”

NASA hoped — as recently last last year — to launch the Webb observatory in October, but mistakes made by teams at Northrop Grumman stacked up to delay the mission’s launch. Agency managers acknowledged last September the launch would slip to 2019, then officials said in March that the mission would not be ready for liftoff until May 2020.

NASA officials ordered the review board to determine when Webb could be ready for launch, and how much it will cost to recover from the testing errors and complete development of the observatory.

The review panel concluded NASA was still being too optimistic in its schedule predictions, and a new problem uncovered after an acoustic test on the spacecraft earlier this year added to the delay. NASA agreed with the review board’s schedule assessment, and set a new target launch date of March 30, 2021.

“The cost of this delay (from 2018) is estimated by the IRB (Independent Review Board) to be $1 billion,” Young said in a conference call with reporters Wednesday. “This 29-month delay is caused by five factors: human errors, embedded problems, lack of experience in areas such as the sunshield, excessive optimism, and systems complexity.”

Young said the panel agreed with NASA and astronomers on Webb’s scientific importance, and they concluded the mission should proceed toward launch. NASA considers Webb the top priority for the agency’s science division.

Webb’s total cost to NASA is now projected to be $9.66 billion, the space agency said, including post-launch operations and data processing expenses. The cost to complete development of the observatory is now forecast to be around $8.8 billion, exceeding the $8 billion development cost cap mandated by Congress in 2011.

Lawmakers will have to formally reauthorize the mission after the budget breach.

Steve Jurczyk, NASA’s associate administrator, said the agency has submitted a report to Congress detailing Webb’s new schedule and cost estimates. NASA will seek reauthorization from Congress in the coming months, Jurczyk said.

He said NASA’s re-plan requires $837 million in additional funding to complete development of the observatory.

Jurczyk added that NASA has sufficient funding this year to continue working on the observatory, and begin implementing the 32 recommendations proposed by the Independent Review Board.

“We will need additional funding for this plan in 2020 and 2021, and we’re in the process of defining our budget request for 2020 right now,” he said.

Young cited several errors made by Northrop Grumman that contributed to the delay to 2021.

In one example, technicians used the wrong solvent to clean propulsion valves on the spacecraft, damaging the sensitive components. Northrop Grumman should have checked with the supplier of the valves to ensure the cleaning agent was compatible, Young said.

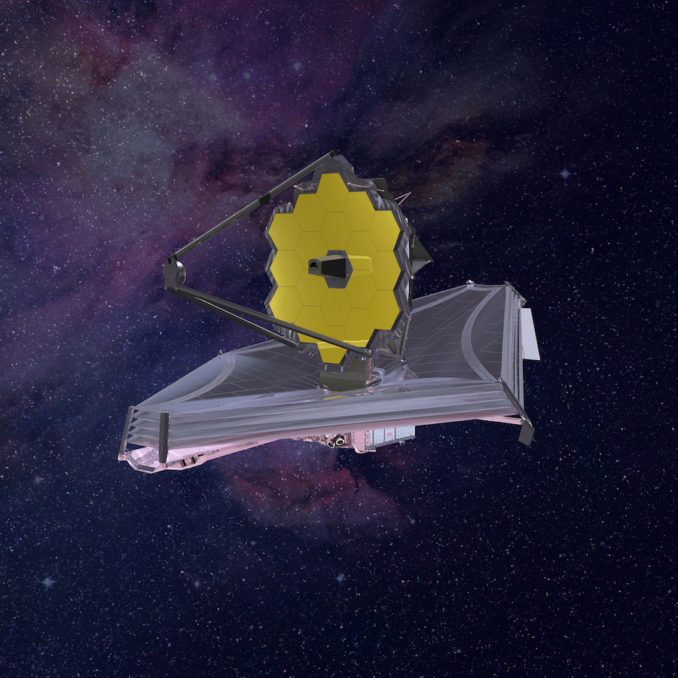

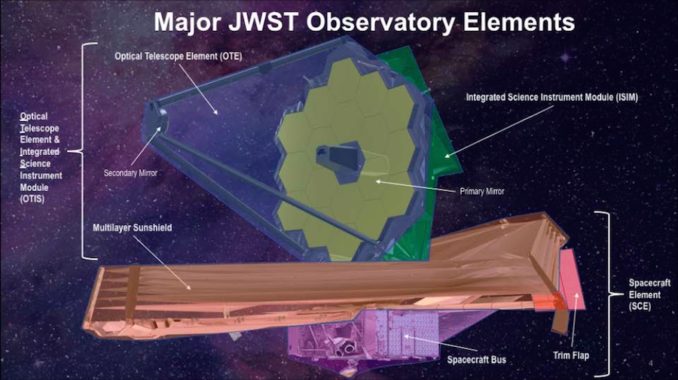

Northrop Grumman’s team also applied excessive voltage to transducers, and improperly installed fasteners on Webb’s sunshield, which will launch in a folded configuration and then unfurl to the size of a tennis court once in space. The five-layer sunshield will keep Webb’s telescope and instruments in shadow and cool enough to detect faint infrared light from faraway stars and galaxies.

The fasteners came loose during an acoustic test that simulated the conditions Webb will encounter during launch on a European Ariane 5 rocket from French Guiana.

Some of the fastener hardware, which comprised items such as washers and screws, still has not been found on the spacecraft or in Northrop Grumman’s test facility in Redondo Beach, California. If any of the loose hardware is still on the spacecraft, engineers should find it as Webb goes through deployment testing, according to Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s science mission directorate.

“We’ll remain focused on it until we’re 100 percent confident that every one of these pieces has been found,” he said.

“Eliminating errors in the procedure for installing the fasteners would have prevented this problem,” Young said, who added that the mistakes could have been avoided by “simple fixes that were not implemented, (which) resulted in approximately a one-and-a-half-year schedule delay and a cost of about $600 million.”

“Human problems are mistakes made by people working on the flight hardware, or developers of procedures that dictate how work on the flight hardware is to be conducted,” Young said.

Workers also discovered tears in the sunshield after a deployment test, and those tears have been repaired. Further sunshield deployment tests are planned to ensure that problem does not occur again.

Young said many of the review board’s recommendations are aimed at minimizing human errors, and reducing their impact to Webb’s overall schedule and budget if they do happen.

“By appropriate discipline, training and procedures, you can minimize any impact that they have,” Young said.

The panel also recommended NASA examine work already completed on Webb. The audit could uncover problems before they would otherwise be discovered during testing, or after launch, Young said.

NASA also concurred with the board’s recommendation that a manager be appointed to oversee Webb’s commissioning, a high-risk phase of the mission after launch during which numerous appendages and components will be extended and unfurled to configure the observatory for science observations.

Northrop Grumman has revamped procedures and made personnel changes on the Webb team, and NASA has added managers and engineers providing oversight of the contractor’s work, officials said.

“Of course, Northrop is part of this, but we have oversight of this, so we take responsibility as well,” Zurbuchen said.

Jurczyk said NASA’s contract with Northrop Grumman allows the agency to evaluate the company’s performance.

“Every six months, we lay out a performance plan for them that we evaluate them on, and then they earn award fees, which is their profit based on their performance,” Jurczyk said. “Their award fees have reflected their performance in the previous periods, and they’ll reflect performance as we move forward. That’s how we hold them accountable and reward them for good performance, and not for not-so-good performance.”

The schedule and budget woes now afflicting the ambitious Webb observatory are the latest in a string of troubles since the mission was first conceived in the 1990s. Webb’s launch has been delayed more than a decade, and its total cost has ballooned to more than $10 billion, including contributions from NASA’s partners in Canada and Europe.

All components of the observatory are in a clean room at Northrop Grumman’s Redondo Beach plant, where technicians will connect JWST’s spacecraft platform to the mission’s telescope and science module, which arrived at the Northrop Grumman facility earlier this year following assembly at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland and a cryogenic vacuum test at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

The telescope and instruments have passed their standalone tests, but the spacecraft is still going through its test campaign. Once the two major segments of the observatory are mated, the entire vehicle will undergo another round of testing, including further checks to verify Webb’s sunshield, solar panels, mirrors and antennas all unfurl as designed after launch.

Billed as a successor to the famous Hubble Space Telescope and named for former NASA Administrator James Webb, the multibillion-dollar observatory will be parked in an orbit near the L2 Lagrange point nearly a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth. The telescope’s detectors will be chilled as cold as minus 448 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 266 degrees Celsius).

Webb’s 21.3-foot (6.5-meter) primary mirror is made up of 18 segments, each with mechanical motors to perfectly align the telescope once in space. The mirror is more than six times larger than Hubble’s, giving Webb more than 100 times its predecessor’s sensitivity.

“Using infrared spectroscopy and unparalleled sensitivity and resolution to detect the faint infrared light of astronomical objects, Webb’s discoveries will revolutionize and enrich our understanding of the universe and our cosmic origins, helping to answer questions like, ‘Are we alone in the universe?'” said John Mather, Webb’s project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“Webb is world-class,” Mather said. “From detecting the first stars and galaxies in the distant universe to probing the atmospheres of nearby exoplanets for possible signs of habitability, (Webb) will underpin many other astrophysics projects.”

“I would say we’re certainly annoyed that we have to wait because that telescope seemed like it was right away, coming soon, and we have already decided what to do with the first half-year observations,” Mather said Wednesday. “So we’re going to have to wait, but on the other hand, I think we’re really pleased that we’re going to make sure that it works. It will be worth the wait.”

Zurbuchen said Wednesday that lawmakers and White House officials agree that Webb’s scientific potential is “compelling,” but he said it is to early to gauge how Congress will respond to the latest delay.

“I think it would be premature to give … a real sense of where we’re going,” he said.

Several members of Congress weighed in with statements Wednesday.

“While I am deeply disappointed by what has come to light over the last several months, I believe the discoveries we will get from the James Webb Space Telescope will be worth the cost of completing the mission — which is what the Independent Review Team recommended,” said Sen. Bill Nelson, D-Florida. “Imagine if we had chosen not to continue the Hubble Space Telescope after its problems were discovered? But we also need to do some soul-searching to find out how to better manage large, complex and ambitious programs in the future.”

“The James Webb Space Telescope has tremendous potential to expand our knowledge of our solar system and our universe,” said Rep. Lamar Smith, R-Texas, chairman of the House Science, Space and Technology Committee. “Program delays and cost overruns don’t just delay the JWST’s critical work, but they also harm other valuable NASA missions, which may be delayed, defunded, or discarded entirely.”

Smith added that the committee will analyze the Independent Review Board’s report, “as we work to ensure accountability and efficiency in the JWST project.” He said a committee hearing is scheduled next month with Bridenstine, Young and Northrop Grumman chief executive Wes Bush to address the report’s findings.

Webb escaped the threat of cancellation in 2011 after lawmakers proposed zeroing the mission’s budget. In the wake of Webb’s near-cancellation, NASA and Congress agreed to aim for the observatory’s launch in 2018.

Zurbuchen said the European Space Agency, which is providing the launch vehicle for Webb as part of its contribution to the mission, has assured NASA an Ariane 5 rocket will be available for the observatory in 2021.

ESA and Arianespace, the French company which operates the Ariane rocket family, plan to retire the Ariane 5 launcher by the end of 2022 in favor of the less expensive Ariane 6 rocket set to debut in 2020.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.