STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

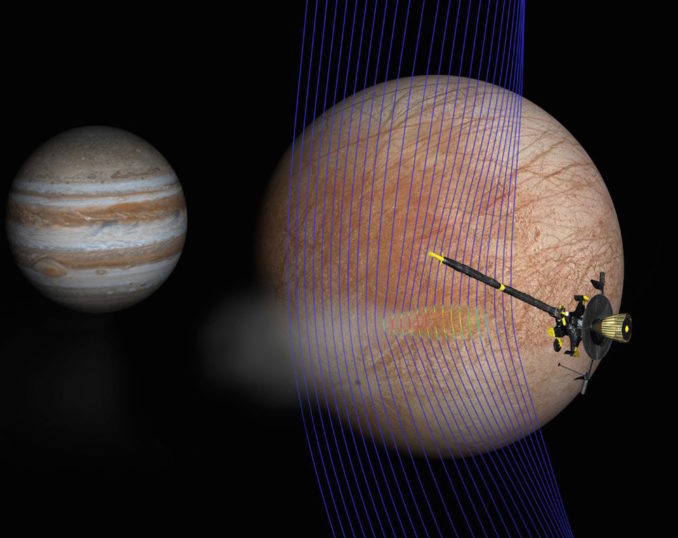

A review of data captured by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft as it orbited Jupiter in the 1990s indicates it likely flew through a plume of water vapor spewing from cracks in the surface of the moon Europa, providing independent evidence water is being released from a vast sub-surface ocean beneath its frozen crust, scientists said Monday.

The Galileo data are consistent with earlier observations by the Hubble Space Telescope that captured signs of presumed plumes at the limits of detectability. In both cases, the data indicate plumes erupted from roughly the same region, a known thermal “hot spot” on the moon’s surface.

The Galileo data were collected in 1997 during a Europa flyby at an altitude of less than 250 miles. The spacecraft’s magnetometer, used to detect and measure magnetic field strength, and its plasma wave spectrometer, which measured charged particles in the environment, both recorded readings best explained by passage through a plume of water vapor, according to the new analysis.

The magnetometer detected a field rotation across hundreds of miles and a brief, sharp change in field strength while the plasma wave instrument recorded a substantial increase in the density of charged particles near the spacecraft.

“The material that is coming out from Europa is probably electrically neutral, it’s probably dominated by water vapor,” said Margaret Kivelson, professor emerita of Space Physics at the University of California who led the Galileo magnetometer team. “But there are lots of energetic particles in the environment of Europa and they ionize the material, so they make it an electrically charged.

“And it’s those electrically charged parts of the plume that cause the changes in the magnetic field and change the density of the electrons in the environment that were measured by the plasma wave instrument. So it’s not a direct effect on the environment from the plume, it’s a two-step process.”

Xianzhe Jia, an associate professor at the University of Michigan who led the team that re-assessed the Galileo data, said the location, duration and variations seen in the magnetometer and plasma wave data are consistent with the presumed plume seen by Hubble.

“These results provide strong independent evidence of the presence of plumes at Europa,” he concluded in a paper published Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Not everyone is convinced. Mike Brown, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology, said in a tweet he is a “big Europa fan,” but “so far, all of the evidence for plumes on Europa has been hopeful, rather than truly convincing. I’d love there to be plumes, but I think we should all retain a healthier skepticism here.”

Others found the evidence more compelling. Morgan Cable, an astrochemist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told Scientific American “up until this paper, I was very skeptical the plume existed. … But this has made me a believer.”

Launched in 1989, Galileo became the first spacecraft to orbit Jupiter six years later. Between 1995 and 2003, the nuclear-powered orbiter trained a suite of sophisticated instruments on Jupiter’s turbulent atmosphere and its many moons, focusing on the four large Galilean satellites – volcanic Io and the icy worlds Europa, Callisto and Ganymede.

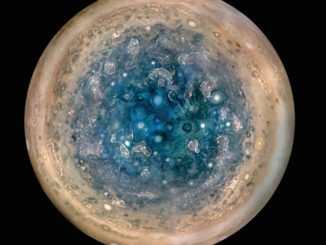

Earlier observations of Europa by NASA’s Voyager probes revealed a chaotic cracked surface that could be explained by tidal stresses, imposed by Jupiter’s gravity, if a layer of warmer ice or even liquid existed below the moon’s frozen crust.

Galileo made 12 close flybys of Europa and detected disruptions in Jupiter’s magnetic field around the moon that also could be interpreted as evidence of a global sub-surface sea of salty water.

Since then, Europa and, more recently, Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus, where visible plumes of water vapor were detected and directly sampled by NASA’s Cassini probe, have been considered prime targets in the search for habitable environments — and possibly life — across the solar system.

Life as it is known on Earth requires energy, organic compounds and liquid water, and all three may be present below the surface of Europa. But determining habitability will be a major challenge.

NASA is designing a spacecraft called the Europa Clipper to study the moon and its environment in a bid to do just that. Expected to launch in the mid 2020s, the Europa Clipper will be equipped with nine instruments, including high-resolution cameras, spectrometers and an ice-penetrating radar to measure the thickness of the crust and to look for signs of sub-surface water.

The Clipper also will look for evidence of recent water eruptions and search for tell-tale atoms and molecules in the moon’s thin atmosphere that might be left over from past or ongoing geysers. The spacecraft will make repeated flybys of Jupiter and more than 40 close passes by Europa at altitudes as low as 16 miles.

The European Space Agency also is planning a mission, known as JUICE, for JUpiter ICy moons Exlorer, that will arrive in 2029 and spend three years studying the planet, Europa, Callisto and Ganymede.

In the meantime, evidence that Galileo flew through a plume of water vapor jetting from the interior of Europa has fired imaginations.

“There now seem to be too many lines of evidence to dismiss plumes at Europa,” Robert Pappalardo, Europa Clipper project scientist at JPL, said in a statement. “This result makes the plumes seem to be much more real and, for me, is a tipping point.”

If the plumes do, in fact, exist “and we can directly sample what’s coming from the interior of Europa, then we can more easily get at whether Europa has the ingredients for life, Pappalardo added. “That’s what the mission is after. That’s the big picture.”