China’s Tiangong 1 space lab, home to two astronaut crews in 2012 and 2013, fell back to Earth uncontrolled Sunday, likely burning up over the Pacific Ocean as satellite trackers monitored the module’s gradual descent from orbit.

The bus-sized spacecraft re-entered Earth’s atmosphere at approximately 8:16 p.m. EDT Sunday (0016 GMT Monday) over the southern Pacific Ocean, according to the U.S. military’s Joint Force Space Component Command, which tracks objects orbiting Earth using a network of radars and optical sensors.

“One of our missions, which we remain focused on, is to monitor space and the tens of thousands of pieces of debris that congest it, while at the same time working with allies and partners to enhance spaceflight safety and increase transparency in the space domain,” said Maj. Gen. Stephen Whiting, deputy commander of the Joint Force Space Component Command, and commander of the 14th Air Force.

The U.S. military publishes orbital parameters on all unclassified objects in its catalog, sharing the data with satellite operators and foreign governments to reduce the risk of collisions in space.

“All nations benefit from a safe, stable, sustainable, and secure space doman,” Whiting said in a statement. “We’re sharing information with space-faring nations to preserve the space domain for the future of mankind.”

The China Manned Space Agency, which oversees the country’s human spaceflight program, confirmed the Tiangong 1 spacecraft’s re-entry in a brief statement early Monday. A control center in Beijing monitored the spacecraft’s descent, and most of Tiangong 1 was expected to burn up during re-entry, Chinese officials said.

Tiangong 1’s re-entry corridor was confined by its orbital ground track between 42.8 degrees north and south latitude, and the space lab could have come back to Earth anywhere along its orbit.

Launched in September 2011, Tiangong 1 was the first prototype for a planned Chinese space station. Three visiting Shenzhou spaceships, one without a crew and then two with three astronauts on-board, docked with Tiangong 1 to test out automated and manually-controlled rendezvous procedures.

Chinese engineers lost control of Tiangong 1’s orbit in 2016.

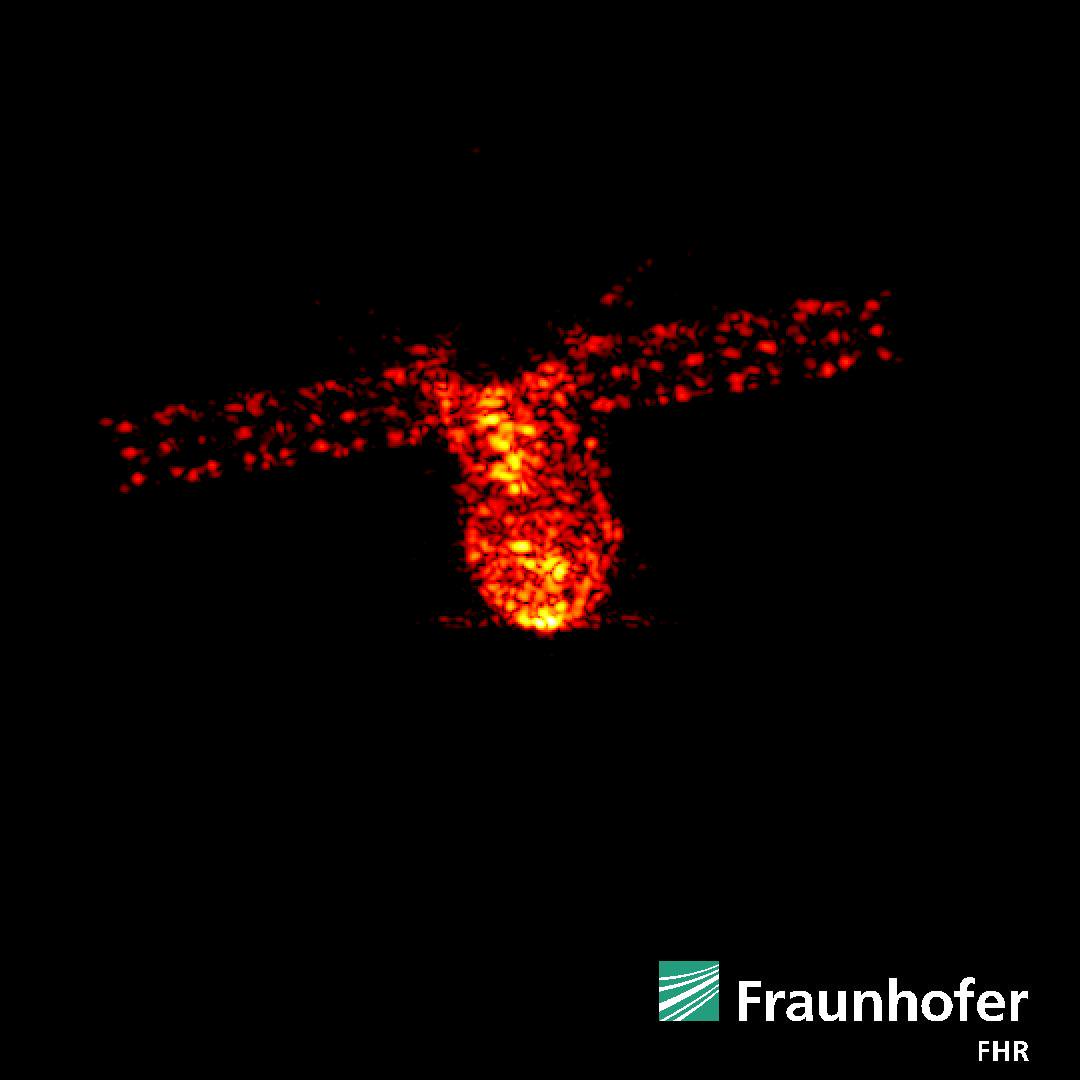

Measuring around 34.1 feet (10.4 meters) long with solar panels extending to a tip-to-tip span of 60 feet (18.4 meters), Tiangong 1 was larger than most defunct satellites that fall back to Earth. But Tiangong 1 was not a record-holder.

A list of the most massive human-made space objects that have plunged back to Earth compiled by Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist who tracks space activities, registered Tiangong 1 as the 49th biggest spacecraft to re-enter uncontrolled.

The eight-ton Tiangong 1 would have been dwarfed by the space shuttle Columbia, which lost control during re-entry in 2003, killing seven astronauts and spreading debris across East Texas and Louisiana. NASA’s Skylab space station had a mass of more than 80 tons (around 75 metric tons) when it came down over Australia in 1979.

More recently, large disused Russian rocket stages have come back to Earth, and the failed Phobos-Grunt Mars probe re-entered uncontrolled in 2012. All were more massive than Tiangong 1.

China launched an upgraded human-rated experiment lab, Tiangong 2, in September 2016. It hosted a two-person crew launched on the Shenzhou 11 spaceraft for a month-long expedition later that year.

The centerpiece of a larger Chinese orbital complex is scheduled to launch in 2020, a couple of years later than previously planned, according to Chinese state media.

The Tianhe 1 command module will launch on a Long March 5 rocket, China’s most powerful launcher. The Long March 5 failed on its second test flight in 2017, and a third demonstration is scheduled for late this year before Chinese officials commit to putting more valuable payloads on the rocket, including a lunar sample return probe, a Mars rover and pieces of the Chinese space station.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.