Blaming a slew of technical snags and “avoidable errors,” NASA officials said Tuesday that the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, already years behind schedule, will be delayed to 2020, potentially pushing the mission’s development cost above an $8 billion cap mandated by Congress.

Problems encountered in recent months with the observatory’s spacecraft bus, the section that will host the mission’s expandable telescope after liftoff, prompted a review of the schedule engineers need to prepare it for liftoff.

“The project has achieved numerous successful milestones, and in fact, 100 percent of the observatory’s flight hardware is now complete,” said Robert Lightfoot, NASA’s acting administrator. “However, work performance challenges that were brought to light have prompted us to take some action.

“We need to successfully integrate both halves of the observatory into the final flight configuration and complete some vital testing after an independent assessment of the remaining tasks,” Lightfoot said Tuesday in a conference call with reporters. “Frankly, the tasks are taking longer to complete than we expected, which will result in a new target launch window, which we now expect to be approximately May of 2020.”

NASA announced last September that JWST would miss its target launch date in October 2018, but managers still expected the observatory to be ready for liftoff between March and June of 2019. Officials on Tuesday said that was no longer possible.

All components of the observatory are in a clean room at Northrop Grumman’s satellite factory in Redondo Beach, California, where technicians will connect JWST’s spacecraft platform — still under construction — to the mission’s telescope and science module, which arrived at the contractor’s plant earlier this year following assembly at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland and a cryogenic vacuum test at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

The telescope and instruments have passed their standalone tests, but the team in charge of building the spacecraft has run into problems, NASA officials said. A NASA review board determined earlier this month that the mission would likely not be ready to launch until 2020.

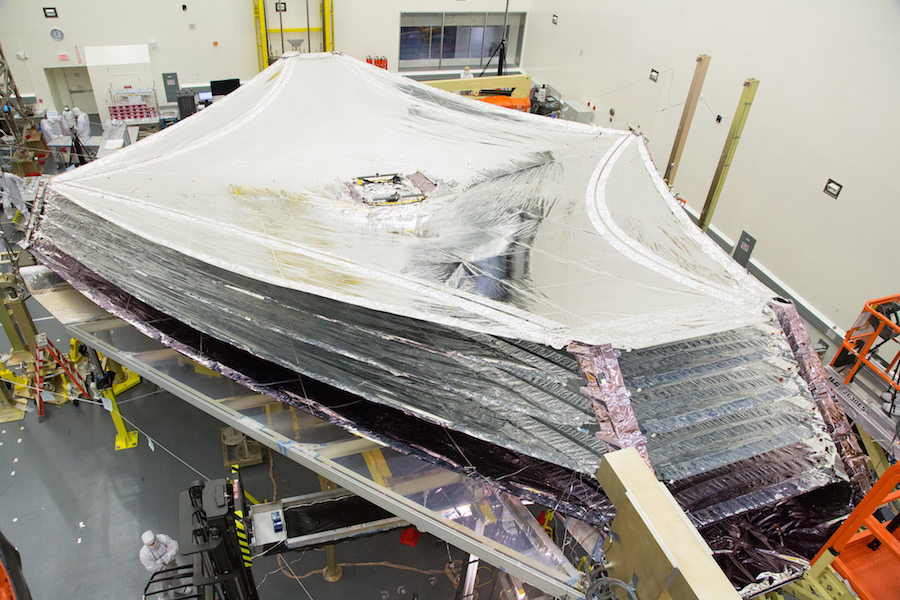

“More time is needed to test and integrate the highly complex sunshield and spacecraft section at Northrop Grumman,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s science mission directorate. “That is taking longer to complete, and there are also a few mistakes that happened.”

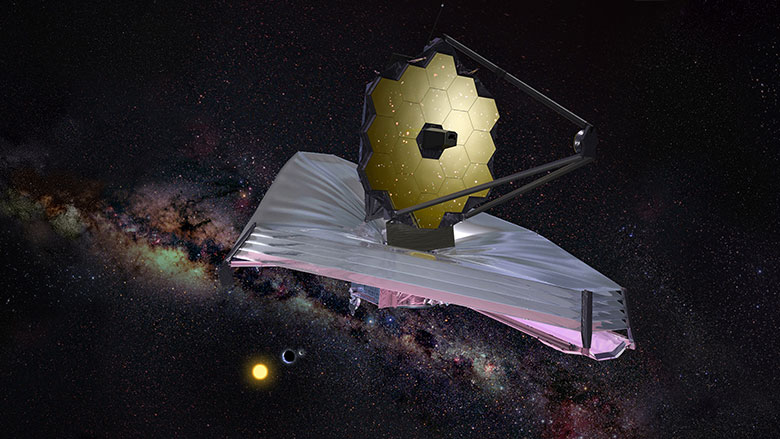

The flagship mission will be the most ambitious astronomical observatory ever launched, building on a quarter-century of discoveries made by NASA’s famous Hubble Space Telescope. Originally proposed more than 20 years ago, the James Webb Space Telescope has been redesigned to expand its observing power and overcome numerous technical hurdles, ballooning costs from an original projection below $1 billion to more than $10 billion, a figure that includes planned launch and operations expenses, along with European and Canadian contributions.

The new observatory will be stationed nearly a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth, using a 21.3-foot (6.5-meter) mirror and four science instruments hidden behind a thermal sunshield to peer into the distant universe, studying the turbulent aftermath of the Big Bang, the formation of galaxies and the environments of planets around other stars.

Lightfoot said NASA has invested $7.3 billion to date in the James Webb Space Telescope, named for the NASA administrator who led the agency during the Space Race of the 1960s.

NASA remains committed to the observatory, but with the launch delay to 2020, the cost to develop the mission could rise above an $8 billion limit set by lawmakers. If that happens, the mission must be reviewed and reauthorized by Congress.

“The James Webb Space Telescope is our highest priority science project within NASA’s science mission directorate,” Lightfoot said. “It’s really a tremendous feat of human engineering, and it’s going to leave a legacy of exceptional science and technical innovations for decades. It’s loaded with pioneering technology, and it’s also the largest international space science project in U.S. history.”

NASA officials did not provide a new cost estimate to finish development of the observatory. Agency leaders will submit a report to Congress by late June to inform lawmakers of the mission’s updated schedule and budget.

“The moment we have any indication that a breach will happen, both in schedule and cost, we need to inform right away,” Zurbuchen said. “The disadvantage of that kind of sudden action is that we have not fully done all our entire joint analysis of cost and schedule, and we actually, at this moment in time, don’t really fully know what the exact cost will be of the entire completed and deployment spacecraft.”

If NASA needs relatively little extra money to complete JWST, future expenditures planned for the observatory’s post-launch operations could be applied to finish assembly and testing of the spacecraft on Earth, Zurbuchen said. If the budget ends up well above NASA’s previous expectation, the impacts to the agency’s other science missions could be more severe, assuming Congress gives the green light to proceed with the observatory’s final testing and launch.

Zurbuchen and his deputy in NASA’s science mission directorate, Dennis Andrucyk, said a series of problems beset the observatory’s spacecraft module over the last year.

“There have been a couple of technical challenges … primarily in the propulsion system, we’ve had a schedule delay due to a transducer that was incorrectly powered,” Andrucyk said. “We needed to replace that. That resulted in a three-month hit. Incorrect solvent was run through prop system. As a result, we wound up having to replace valves in that system, and a catalyst bed heater was accidentally overstressed (at the wrong voltage) and needed to be replaced.”

Andrucyk characterized the propulsion system issues as “avoidable errors.”

“The sunshield complications also took a toll on the schedule,” he said. “It’s a very large five-layer membrane sysstem about the size of a tennis court, and during the deploy, fold and stow operations, the amount of time that we expected to perform those activities took longer than we expected. The first deploy we expected to be two weeks. It wound up being a month, and in the fold and stow, we expected it to be about a month, and it wound up being two months. We have two additional of those deploy, fold and stow operations to go.”

Engineers discovered seven tears across five of the sunshield membranes, which will ensure the observatory’s detectors and mirrors remain protected from heat and light from the sun, keeping parts of the spacecraft as cold as minus 370 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 223 degrees Celsius. Internal coolers will chill some of the telescopes’s sensors even colder.

“Also, the sunshield tensioning system, the cables that hold the sunshield membrane into its shape, developed too much slack during the deployment, creating a snagging hazard,” Zurbuchen said. “So they had to redesign how the cables straddle certain parts of the boom so that wouldn’t happen.”

The sunshield tears have been repaired, officials said.

Once the telescope and spacecraft sections are connected, ground crews at Northrop Grumman will again deploy the sunshield, along with the telescope’s unfoldable wings and other structures, then put the entire observatory through electrical, vibration and acoustic tests. After those checks are complete, technicians will unfurl the full observatory once more before stowing it into launch configuration.

The testing is geared toward ensuring the mission’s post-launch deployments go off without a hitch.

The sunshield and mirror will fold up origami-style to fit inside the envelope of the European Ariane 5 rocket that will launch JWST from French Guiana. The Ariane 5 launcher is one of the European Space Agency’s major contributions to the mission, along with key instrument hardware.

Depending on how you count, JWST will have more than 300 deployments after it separates from from the upper stage of the Ariane 5 launcher. Counting steps in a similar way, the Curiosity Mars rover had around 70 deployments.

“Webb is really complex,” Zurbuchen said. “Extensive and rigorous testing is necessary to ensure that we have a launch, deployment and checkout that succeeds with high confidence.

“Webb will journey to an orbit about a million miles from the Earth, four times farther than the moon,” Zurbuchen said. “Simply put, we have one shot to get this right before going into space. You’ve heard this before, and it rings true for Webb, for us, really failure is not an option.”

Andrucyk said NASA Headquarters will have more oversight over JWST in the future, including direct interaction with Northrop Grumman’s president and chief operating officer. NASA will also dispatch a project manager to Northrop Grumman’s factory in Southern California on a permanent basis, along with additional NASA spacecraft integration and test experts during critical operations.

NASA will also have daily and weekly schedule reviews with Northrop Grumman, which will also revamp its management structure. Northrop Grumman is also making personnel changes and updating procedures.

Andrucyk said Tuesday at a meeting at the National Academies of Sciences that some of the recent JWST problems “were driven by poorly written procedures.”

“Northrop Grumman remains steadfast in its commitment to NASA and ensuring successful integration, launch and deployment of the James Webb Space Telescope, the world’s most advanced space telescope,” Northrop Grumman said in a statement.

An independent review board chaired by Thomas Young, a space industry veteran who served as an executive at Lockheed Martin and as mission director of NASA’s Viking Mars landers, will help the space agency confirm a new target launch date and cost figure for JWST.

NASA’s standing review board estimated the mission could be ready for launch by April 30, 2020, at a 70 percent confidence level, Andrucyk said at the National Academies of Sciences’ Space Science Week meeting Tuesday. That led the agency’s leaders to announce the mission was likely off until May 2020.

For the record, Andrucyk said, NASA’s standing review board — comprised of engineers and managers not part of the JWST program — concluded the mission could launch in January 2020 with 30 percent confidence.

“Today’s announcement that the James Webb Space Telescope launch will slip again and likely go over the $8 billion development cost cap is disappointing and unacceptable,” said Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Texas), chairman of the House Science Committee.

Smith added in a statement that the delays and cost overruns “undermine confidence in NASA and its prime contractor, Northrop Grumman.”

“NASA must keep their promises to the American taxpayers,” Smith said. “Every time a mission is delayed or goes over budget, it negatively affects other science missions. This includes delays, cancellations and de-scoping of other missions. Those effects ripple out within NASA and through the entire scientific community.

“The James Webb Space Telescope is a crucial project and an investment in our future,” Smith concluded in his statement. “I expect it to be completed within the cap and launched as close to on schedule as possible so we can look forward to the incredible discoveries it will bring.”

The observatory survived a brush with cancellation by lawmakers in 2011, who proposed zeroing the mission’s budget. An independent review in 2010 found that the mission needed more money to maintain a target launch date in 2015, and NASA and Congress eventually agreed to aim for JWST’s launch in 2018, with additional funding to give managers a budget reserve to handle potential technical issues.

That funding reserve may prove insufficient, and officials admitted Tuesday that a 2018 launch was based on an optimistic schedule.

The Webb mission is set to become the most expensive robotic science mission ever launched. The observatory’s primary mirror — which collects light from astronomical sources — is nearly three times the diameter of Hubble’s, and no other observatory of JWST’s size is planned for launch until at least the 2030s.

Webb will enable “science that will look at the universe in a way we have never seen it,” Zurbuchen said.

With another announcement that Webb’s costs are rising, some worry that the mission’s budget will hamstring NASA’s ability to secure approval for future flagship-class science missions. Zurbuchen said missions like JWST have strong value, pushing frontiers in technology and scientific productivity that make future probes possible.

“One conclusion you could make is you shouldn’t do complex missions like this,” Zurbuchen said Tuesday afternoon at the National Academies of Sciences. “I will tell you that this would be a very grave and wrong assumption. At NASA, and together with our international partners, we should push the envelope.

“What we should do is not make stupid mistakes,” he said. ‘We should learn as we go, as fast as we can.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.