Rocket Lab’s commercial Electron launcher soared into orbit from New Zealand on Saturday, U.S. time, a success that puts the company’s founder said will hasten dedicated, frequent and affordable rides to space for small satellites.

The achievement caps four years of development by Rocket Lab’s U.S.-New Zealand team and affirms the company’s place in the world’s fast-growing commercial space sector.

“Obviously, we’re very happy,” said Peter Beck, Rocket Lab’s founder and CEO. “It marks the conclusion of a huge amount of work.”

Beck said the rocket’s on-target orbital delivery, on only its second flight, should allow a quick transition to operational, revenue-earning missions in the coming months. Rocket Lab’s backlog includes several missions for commercial clients, along with one launch contract with NASA.

“What was really important to us when we developed this vehicle was not to develop something to just get to orbit, and that’s it, but to develop something that once we got there, was ready to go fully commercially,” Beck said in an interview with Spaceflight Now shortly after the successful launch.

Standing 55 feet (17 meters) tall, the kerosene-fueled rocket ignited nine Rutherford main engines at 8:43 p.m. EST Saturday (0143 GMT; 2:43 p.m. New Zealand time Sunday). Hold-down restraints opened after a brief health check, freeing the Electron booster for its eight-and-a-half minute climb into orbit.

A live video webcast provided by Rocket Lab showed the rocket rumbling through a mostly sunny summertime sky, and a downward-facing camera aboard the booster captured stunning imagery of Mahia Peninsula, the location of the Electron launch base on New Zealand’s North Island, receding from view.

Engineers based in Rocket Lab’s control center in Auckland, 235 miles (380 kilometers) to the northwest of the launch pad, tracked the launcher’s ascent, confirming good navigation and engine performance as it headed south over the Pacific Ocean with more than 41,000 pounds of thrust.

The nine-engine first stage cut off and jettisoned around two-and-a-half minutes after liftoff, leaving the Electron’s single vacuum-rated Rutherford upper stage engine to steer the rocket into orbit. The launcher’s payload fairing released in two pieces around the three-minute point of the flight, and a spent shoebox-sized battery pack fell away from the upper stage as expected around six-and-a-half minutes after launch.

Made of black carbon composite materials, the 3.9-foot-diameter (1.2-meter) Electron rocket is powered by Rutherford engines, a powerplant developed by Rocket Lab engineers that burns a mixture of kerosene and liquid oxygen.

Each Rutherford engine generates around 4,600 pounds of thrust, using battery-powered pumps to cycle the engine’s liquid propellants, an innovation Rocket Lab describes as “entirely new” in rocket propulsion.

The Electron’s engine, named for the New Zealand-born nuclear physicist Ernest Rutherford, is the first of its type to be primarily 3D-printed. Each Rutherford engine, including its engine chamber, injector, pumps and main propellant valves, can be printed in 24 hours.

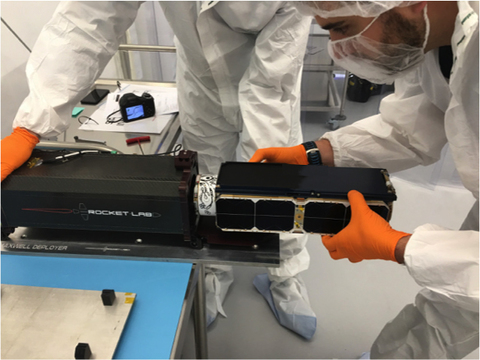

Live video from the second stage showed the second stage’s Rutherford engine turn off on time around eight minutes after liftoff, and Rocket Lab’s webcast commentator announced deployment of the three CubeSats stowed aboard by Spire Global and Planet, two San Francisco-based companies.

Applause and high-fives abounded in the Rocket Lab control center, and Spire and Planet later confirmed their CubeSats successfully separated from the Electron upper stage. They were housed in newly-designed deployers provided by Rocket Lab.

Spire’s commercial CubeSat fleet tracks weather and ship movements, while Planet operates around 200 small spacecraft taking detailed imagery of Earth.

This weekend’s launch came nearly seven months after the maiden Electron rocket fell short of reaching orbit due to a ground tracking error. Controllers lost contact with the launcher on its May 2017 flight, prompting a safety officer to send a command to terminate the mission.

The safety officer followed planned procedures for such an event, but later analysis showed the Electron was performing well, with its second stage engine firing normally.

Rocket Lab shipped its second Electron launcher to Mahia Peninsula late last year, but a series of scrubbed launch attempts and aborted countdowns kept it grounded in December.

Officials pushed back the launch, which Rocket Lab said was still experimental, until January. Two ships strayed into a keep-out zone in the Pacific Ocean downrange from Mahia Peninsula during a launch attempt Friday, U.S. time, and deteriorating weather prevented liftoff once the vessels were cleared from the area.

The long wait was worth the reward in the end, Beck said.

“You’ll hear it from America,” he said of Rocket Lab’s post-launch party.

Tracking data published by the U.S. military indicated the rocket reached an orbit between 179 miles and 331 miles (289-533 kilometers) above Earth, flying around the planet at an angle of 82.9 degrees to the equator.

“We flew right down the middle of our trajectory lines, and not only went into orbit, but went into orbit at a much greater accuracy than even our commercial requirement,” Beck said. “We’re very happy with the flight.”

The U.S. military’s catalog of human-launched objects in orbit also included other items attributed to the Electron flight in a more circular orbit above an altitude of 300 miles (about 500 kilometers). A Rocket Lab spokesperson said the company will release information in the coming days about additional items carried on the launch.

Beck said Rocket Lab has up to nine missions on its schedule in 2018. At full production, the company says it can launch up to 50 Electron rockets per year.

Although Beck founded Rocket Lab in 2006, he said the Electron project only kicked about about four years ago after a series of suborbital sounding rocket tests.

“That’s a short time to go from nothing to orbit,” he said. “What really excites me more though is (when) we got to orbit, we’re ready to hit production, we’ve got factories built up, and vehicles are coming through them. But what excites me the most is, the way we see it, this ushers in a new era and a beginning of a new commercial access to space with small launch vehicles, rapid, dedicated and frequent.”

The company says it will charge $4.9 million per Electron flight, significantly less than any other launch provider flying today, and offer a solo ride for payloads that currently must ride piggyback with a larger payload.

With money from venture capital funds in Silicon Valley and New Zealand, along with a strategic investment from Lockheed Martin and the government of New Zealand, Rocket Lab completed the design and qualification of the Electron rocket with less than $100 million since the company’s founding, according to Beck.

A further round of venture capital financing last year brought the total investment in Rocket Lab to $148 million, valuing the company at more than $1 billion. Beck said Rocket Lab is now fully funded, with no further investment rounds in the pipeline.

Rocket Lab is one of several companies — alongside start-ups and spinoffs like Virgin Orbit and the now-defunct Texas-based rocket developer Firefly — that have been established in recent years to meet demand for launches in the small satellite market.

Virgin Orbit’s air-dropped LauncherOne vehicle is currently in full-stage ground testing ahead of an inaugural orbital test flight in mid-2018. Another company, Vector, says it will also attempt its first launch to orbit with a small satellite booster later this year.

But Rocket Lab is the first of the bunch to reach orbit.

“I love being first,” Beck said.

Rocket Lab says the Electron rocket can place up to 330 pounds (150 kilograms) into sun-synchronous orbit 300 miles (500 kilometers) above Earth. The booster is sized to haul clusters of CubeSats to orbit, or launch replacement craft for huge constellations of telecom and Earth-imaging satellites.

The benefit of a dedicated ride, small satellite owners say, is the ability to choose when and where to launch. Piggyback payloads are usually at the whim of bigger, more expensive satellites riding the same rocket, forcing their owners to compromise on the flight’s orbital destination, or putting operators at additional risk of delays.

India’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle, United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5, and Russia’s Soyuz rocket are among the launchers commonly flying with secondary payloads, a concept known in the industry as “rideshare.”

The idea of an express ride to orbit for microsatellites is not new.

Orbital ATK designed and debuted its air-launched Pegasus rocket more than a quarter-century ago, and it found business in launching commercial, military and NASA satellites. But its cost is out of the reach of entrepreneurial space companies.

SpaceX’s Falcon 1 rocket was designed to loft slightly heavier payloads than Rocket Lab’s Electron, and SpaceX charged around $7.9 million per flight. But the Falcon 1 last flew in 2009, and SpaceX shelved the program in favor of its bigger Falcon 9 launcher.

Those experiences lead some in the space industry to say the jury is still out on the profitability and sustainability of new small satellite launch ventures.

“We, at SpaceX, started with a small launch vehicle, and I really wanted to make a business of the Falcon 1 as a small, very light-lift launch vehicle,” said Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president and chief operating officer, at Euroconsult’s World Satellite Business Week conference in Paris in September.

“We found the only way we could make money was to enhance the capability of that tiny launch vehicle, and make it bigger,” she said. “The bigger you get, obviously, it becomes a little bit more expensive, and we could just not make it work.

“I’d love to see light-lift launchers make a business of it and get some of these other small payloads launched, but that’s a tough business,” she said. “We couldn’t make it, but I do wish them luck.”

Tory Bruno, ULA’s president and CEO, predicted small launcher developers will find a challenge competing with rideshare offerings from entrenched rocket companies.

“I think it’s a function of time,” Bruno said in September. “Initially, they will begin, and they will try to service the smaller satellite market. As that becomes a real marketplace that attracts with test of us, I think the economics will favor rideshare as a solution.”

The head of International Launch Services, Kirk Pysher agreed: “I still believe the most effective and reliable ride for them (small satellites) is one of us sitting up here today.”

Pysher shared the panel with Shotwell, Bruno and executives from Arianespace, China Great Wall Industry Corp. and Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

“There may be a niche market out there for small launchers, but I don’t think it exists today,” he said.

But some satellite operators disagree, backing up their views with signed contracts.

Rocket Lab has secured firm contracts for three dedicated Electron flights for Planet, and Spire Global has agreed to send its CubeSats to orbit on up to 12 Electron rocket launches.

Rocket Lab has also sold one Electron mission to Spaceflight, a Seattle company which aggregates small satellites from commercial, academic and government customers to share launches into orbit.

The U.S.-New Zealand company also commercial launch deal with Moon Express, one of the competitors vying for the Google Lunar X Prize, for at least three missions to send micro-landers to the moon.

NASA is also a Rocket Lab customer. The U.S. space agency signed up to place multiple small research satellites into orbit, committing to a nearly $7 million launch contract in October 2015.

With a launch base, control center and factory in New Zealand, Rocket Lab also has a headquarters in Southern California, where it has second rocket assembly plant that is already churning out engines. Eventually hoping to launch as often as once per week, the U.S.-New Zealand company operates under the regulatory umbrella of the Federal Aviation Administration.

The successful Electron test flight marked the first time a commercial rocket has launched into Earth orbit from the Southern Hemisphere.

“I think there will be a lot of pride in the country,” Beck said of the launch’s reception in New Zealand. “But it’s most definitely a joint effort between the U.S. and New Zealand.”

Beck said Rocket Lab has five Electron rockets currently being manufactured, and officials have a near-term goal of completing one vehicle per month to meet this year’s launch manifest.

Assuming a detailed data review does not uncover an unexpected near-miss on this weekend’s launch, Rocket Lab intends to declare its next flight a fully commercial mission. Officials originally expected to make the first three Electron flights test launches.

A payload for the next Electron launch has not been decided.

“We’re not a one rocket kind of gig here,” Beck said. “There’s a lot more following it, and that’s really the focus now, to move into high-rate commercial production and start clearing some of our manifest.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.