STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

NASA TV coverage of the end of Cassini’s mission begins at 6:30 a.m. EDT (1030 GMT) Friday, Sept. 15.

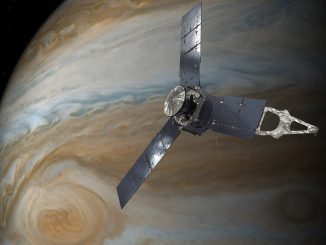

Thirteen years after reaching Saturn, NASA’s nuclear-powered Cassini spacecraft raced through its 294th and final orbit Thursday, collecting priceless data while hurtling toward a kamikaze-like plunge into the ringed planet’s atmosphere Friday, going out in a blaze of glory to wrap up an “insanely” successful mission.

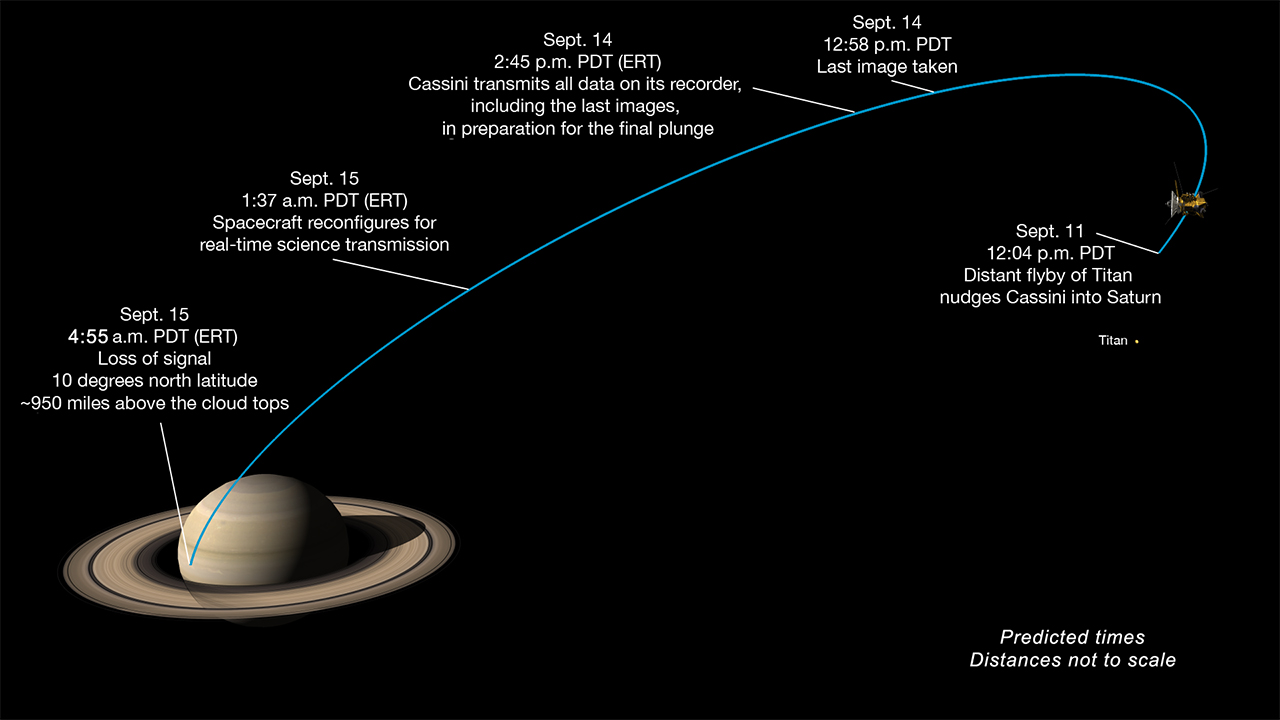

Virtually out of propellant, Cassini used a final gravitational nudge — a “goodbye kiss” — from Saturn’s smog-shrouded moon Titan earlier this week to precisely aim itself at a point on the planet’s dayside 10 degrees above the equator.

“That final flyby of Titan … put Cassini on an impacting trajectory and there is absolutely no coming out of it,” said Earl Maize, Cassini project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

“We are going so deep into the atmosphere the spacecraft doesn’t have a chance of coming out. So that final kiss from Titan, that really is our last flyby, and we will enter Saturn’s atmosphere very early on the morning of Sept. 15.”

Dutifully executing a final set of commands from Earth, Cassini was programmed to snap a final few pictures of Saturn, its vast ring system, Titan and the small moon Enceladus Thursday in what mission managers are calling “the last picture show,” before turning its large dish antenna toward Earth to transmit the images and other data back to waiting scientists.

Titan and Enceladus, which harbors a saltwater ocean beneath an icy crust, host potentially habitable environments and rather than risk an eventual collision with an out-of-gas Cassini — and earthly contamination — NASA managers opted to crash the spacecraft into Saturn to eliminate any possible threat.

“These final images are sort of like taking a last look around your house or apartment just before you move out,” said Linda Spilker, the Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “You look at your old rooms, and memories across the years come flooding back. In the same way, Cassini is taking a last look around the Saturn system … and with those pictures come heart-warming memories.”

Cassini cannot send images back during its final descent, but eight of its scientific instruments will be operating and beaming back data in realtime as the spacecraft, its antenna locked on Earth, slams into Saturn’s discernible atmosphere at 6:31 a.m. EDT (GMT-4) Friday.

Traveling at a velocity of 70,000 mph, Cassini’s demise will be quick. Even so, scientists expect a wealth of data during the probe’s final moments.

“The highest science priority is to sample the atmosphere,” Spilker said. “We stand to gain fundamental insights into Saturn’s formation and evolution as well as processes that occur in the atmosphere.”

Entry will occur when Cassini encounters the first wisps of gasses in the extreme upper atmosphere about 1,190 miles above Saturn’s visible cloud tops, where atmospheric pressure is equivalent to sea level on Earth.

Small thrusters will automatically fire to keep Cassini properly oriented, and its antenna locked on Earth, as atmospheric buffeting begins. But within one minute of entry, about 120 miles into the discernible atmosphere, the thrusters will be overwhelmed, Cassini will begin tumbling and telemetry will come to an abrupt end.

A few moments after that, Cassini will be ripped apart and its components utterly destroyed by extreme heating.

“It goes really fast,” said spacecraft engineer Julie Webster. “First, the (insulation) blankets will burn off, and then we’ll reach the aluminum melting point within about 20 seconds. The iridium will be the last thing to melt, and it will go about 30 seconds after the aluminum. It goes within a minute.”

Cassini’s final signal, traveling across the solar system at the speed of light — 186,000 miles per second — will reach a huge antenna in Australia 83 minutes later, at 7:55 a.m. That’s when flight controllers, engineers and scientists gathered at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory will know Cassini is well and truly gone.

“The mission has exceeded all of our expectations, done better than we could have ever dreamed,” said Curt Niebur, Cassini program scientist at NASA Headquarters. “The Saturn system is absolutely chock full of amazing worlds of all sizes, and Cassini has been exploring them for the past 13 years.

“We’ve watched the particles in the rings around Saturn collide and glide during their gravitational dance and we’ve confirmed things that we suspected might exist in the Saturn system. But even more pleasantly, we’ve been shocked by things that we never predicted we would find.”

Like watching a titanic globe-spanning storm develop and move around the entire planet, running into itself like a snake eating its tail. Like discovering a bizarre hexagon-shaped storm around Saturn’s north pole that has persisted for decades. And the discovery of methane seas, lakes, rivers and rain on Titan, where conditions mimic those on Earth in the distant past.

“And we were absolutely shocked to learn that tiny, tiny Enceladus has a global liquid water ocean underneath a relatively thin ice crust that’s warmed by hydrothermal activity and has jets of water from that ocean shooting out into space through cracks in the south pole,” Niebur said. “Enceladus may have all of the ingredients needed for life as we know it to currently exist, right now, at this very second.”

Over the course of its 13-year mission, Cassini has executed 2.5 million commands, carried out 360 engine burns, completed 162 targeted flybys of Saturn’s moons, taken more than 453,000 images and discovered six previously unknown moons, covering 4.9 billion miles since launch in 1997.

Most important, the spacecraft, built in the early 1990s, collected 635 gigabits of data resulting in nearly 4,000 peer-reviewed scientific papers.

“The mission has been insanely, wildly, beautifully successful,” Niebur said. “And it’s coming to an end. … I find great comfort in the fact that Cassini will continue teaching us up to the very last second.”

Launched in October 1997, Cassini arrived at Saturn in July 2004 and dropped off a lander built by the European Space Agency that successfully completed a parachute descent to the surface of Titan the following January.

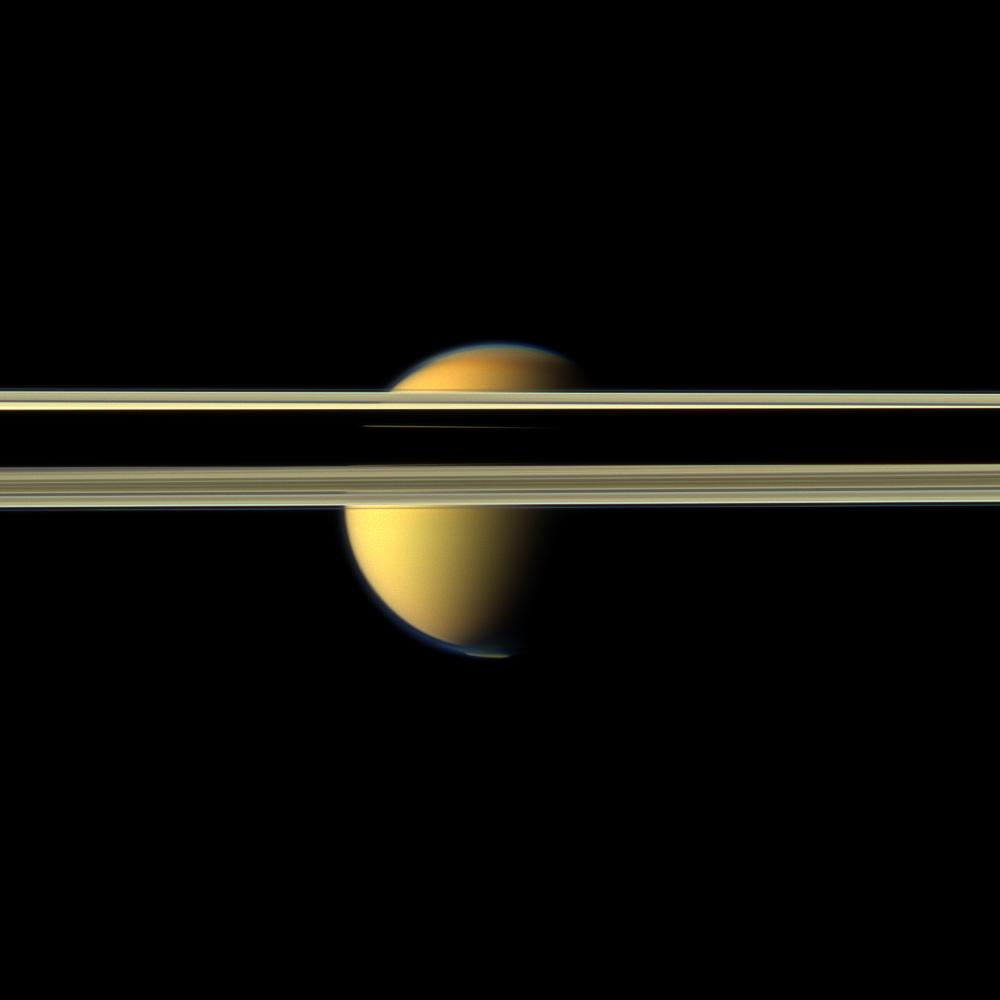

Titan is larger than Mercury but its surface is hidden below a thick smog-like atmosphere. The Huygens lander revealed an alien landscape with rounded rocks and boulders under an orange-hued sky while Cassini’s cloud-piercing radar imaging system eventually filled in a global map of the moon that revealed methane lakes, rivers and seas.

“To put a probe onto Titan, capture a signal on the way down, land it softly on the surface and play those images back, I still give myself goosebumps just seeing that first image,” Maize said. “I’ll never forget it.”

Since then, Cassini has flown through a complex set of ever-changing orbits, repeatedly using Titan’s gravity to alter its trajectory. Energy from the Titan flybys was the equivalent of 127,000 pounds of propellant, Maize said, enabling views of Saturn and its huge ring system from different perspectives and setting up close flybys of and many of its moons.

But all good things must come to an end.

On April 22, Cassini carried out a Titan flyby that kicked off the “Grand Finale,” putting the spacecraft on a trajectory that repeatedly carried it between the innermost rings and Saturn’s cloud tops and set up a mission-ending impact in the atmosphere on Friday.

The Grand Finale orbits brought Cassini closer to Saturn and its rings than ever before and gave scientists a unique opportunity to determine the mass of the rings. While those studies are ongoing, it appears the rings may be a relatively young phenomenon and not a relic of Saturn’s birth.

But for many, discoveries about Titan and Enceladus are the icing on the cake, more than justifying the decision to end Cassini’s mission with a dramatic plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere.

“These two new worlds, Titan and Enceladus, that were so completely revealed to us by Cassini have changed the idea that ocean worlds like Earth and (Jupiter’s moon) Europa are rare in the universe,” Niebur said. “This, in turn, is changing our views about how prevalent and common habitable environments and even life beyond Earth might truly be.”

NASA is in the early stages of designing a spacecraft to make repeated flybys of Jupiter’s moon Europa in the 2020s and many hope a follow-on mission to Saturn will someday be mounted to explore Enceladus in more detail.

‘

“Enceladus has no business existing,” Niebur said. “And yet there it is, practically screaming at us, ‘look at me! I complete invalidate all of your assumptions about the solar system.’ It’s just been a remarkable opportunity to study Enceladus and unveil the secrets it’s been keeping. It’s an amazing destination.”