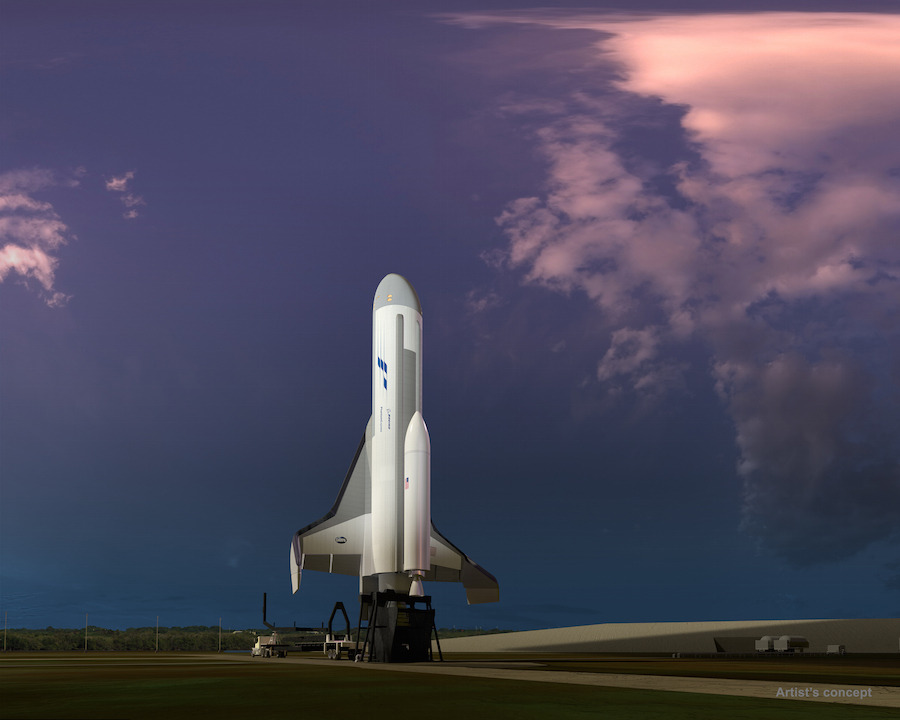

A reusable suborbital spaceplane the size of a business jet being developed by Boeing and the Defense Department’s research and development arm could be launching and landing at Cape Canaveral in 2020, officials said after the defense contractor won a competition last month to design and test the vehicle.

Designed for rapid reusability, the XS-1 spaceplane will take off vertically like a rocket — without a crew — deploy an upper stage after traveling beyond the edge of space, then return to landing on a runway for inspections and reuse.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, selected Boeing to finish designing the spaceplane last month. Boeing beat competitors Northrop Grumman and Masten Space Systems to win the $146 million contract.

Boeing and DARPA are developing the spaceplane in a cost-sharing public-private partnership arrangement, but Boeing did not disclose how much it is spending on the program.

When operational after a series of suborbital and orbital test flights, the XS-1 and its expendable upper stage could place satellites weighing up to 3,000 pounds (1,360 kilograms) into low Earth orbit several hundred miles above the planet.

“The XS-1 would be neither a traditional airplane nor a conventional launch vehicle but rather a combination of the two, with the goal of lowering launch costs by a factor of ten and replacing today’s frustratingly long wait time with launch on demand,” said Jess Sponable, DARPA program manager, in a press release. “We’re very pleased with Boeing’s progress on the XS-1 through Phase 1 of the program and look forward to continuing our close collaboration in this newly funded progression to Phases 2 and 3 — fabrication and flight.”

The Defense Department envisions the Experimental Spaceplane, or XS-1, program as an option for rapid call-up to replace a lost military or commercial satellite, available to launch within days instead of the months or years needed today.

An end goal for the XS-1 program is to launch 10 times in 10 days, with recurring operating costs as little as $5 million per flight, including the disposable upper stage, according to DARPA.

Boeing calls its XS-1 test vehicle the Phantom Express, a winged craft the size of a business jet that will launch to the edge of space and release an expendable upper stage, which would fire to inject the mission’s payload into orbit. The reusable first stage would turn around and fly back to the launch site.

Rick Weiss, a DARPA spokesperson, said Cape Canaveral will be the base for Phantom Express test flights and launch operations. He did not say which launch pad the spaceplane will use.

The spacecraft booster would return to land at one of two runways on Florida’s Space Coast: Kennedy Space Center’s Shuttle Landing Facility, a three-mile-long landing strip, or the Skid Strip at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.

“Phantom Express is designed to disrupt and transform the satellite launch process as we know it today, creating a new, on-demand space-launch capability that can be achieved more affordably and with less risk,” said Darryl Davis, president of Boeing Phantom Works.

Boeing officials said the Phantom Express would employ operation and maintenance principles similar to modern aircraft.

The U.S. Air Force’s X-37B space plane, similar in appearance to the XS-1 but different in function, is also built by Boeing.

The Phantom Express booster stage would be powered by a single Aerojet Rocketdyne AR-22 engine, a version of the space shuttle main engine, burning liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants.

Boeing originally partnered with Blue Origin, the space company founded by Amazon.com’s Jeff Bezos, as an engine provider for the XS-1 program, but later switched to an Aerojet Rocketdyne engine, according to Cheryl Sampson, a Boeing spokesperson.

“We conducted trade studies with Blue Origin in the first phase of the program,” Sampson wrote in an email to Spaceflight Now. “Boeing selected the Aerojet Rocketdyne engine for this next phase as it offers a flight proven, reusable engine to meet the DARPA mission requirements.”

Aerojet Rocketdyne said it will provide two engines for the XS-1 program with “legacy shuttle flight experience to demonstrate reusability, a wide operating range and rapid turnarounds.”

The engines will be designated as AR-22 engines, Aerojet Rocketdyne said in a press release. Technicians at NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi, where Aerojet Rocketdyne assembles and tests rocket engines, will create the AR-22 engines from parts left over from early versions of the shuttle main engine, the company said.

“As one of the world’s most reliable rocket engines, the SSME is a smart choice to power the XS-1 launch vehicle,” said Eileen Drake, Aerojet Rocketdyne CEO and president. “This engine has a demonstrated track record of solid performance and proven reusability.”

The Phantom Express booster stage will have advanced, lightweight composite cryogenic tanks to hold the super-cold propellants feeding the AR-22 engine. Hybrid metallic-composite wings and control surfaces on the spaceplane will be fitted with “third-generation thermal protection” to withstand the rigors of hypersonic flight and re-entry temperatures of more than 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,100 degrees Celsius), according to DARPA and Boeing.

Other technologies on the spaceplane launch system would include an autonomous range safety destruct mechanism and other components designed for autonomous flight, including some developed for DARPA’s Airborne Launch Assist Space Access, or ALASA, program, officials said.

The ALASA program intended to launch small 100-pound (45-kilogram) satellites on a lightweight rocket fired from the belly of an F-15 fighter jet. DARPA canceled the program, which it also developed with Boeing, in 2015 after running into problems testing the rocket’s mix of nitrous oxide and acetylene fuel, a “monopropellant” cocktail that would have eliminated the need for the launcher to carry an oxidizer.

Phase 2 of the XS-1 program will encompass the design, construction and testing of a technology demonstration vehicle through 2019, DARPA said. The AR-22 engine will be test-fired on the ground 10 times in 10 days to verify it is ready for flight tests.

“Phase 3 objectives include 12 to 15 flight tests, currently scheduled for 2020,” DARPA said in a statement. “After multiple shakedown flights to reduce risk, the XS-1 would aim to fly 10 times over 10 consecutive days, at first without payloads and at speeds as fast as Mach 5.”

Then test flights will reach speeds as fast as Mach 10, DARPA said, and deliver a “demonstration payload” into low Earth orbit with a mass between 900 pounds (408 kilograms) and 3,000 pounds (1,360 kilograms).

Weiss said DARPA currently envisions a liquid-fueled upper stage for the XS-1 program, and artist’s concepts show the upper stage riding on top of the spaceplane’s fuselage. The DARPA spokesman said the agency is open to other types of upper stages, which would be provided by Boeing.

DARPA said it will release “selected data” from the XS-1 tests to other commercial launch providers interested in adopting the program’s reusable, rapid-turnaround concepts.

“We’re delighted to see this truly futuristic capability coming closer to reality,” said Brad Tousley, director of DARPA’s Tactical Technology Office, which oversees XS-1. “Demonstration of aircraft-like, on-demand, and routine access to space is important for meeting critical Defense Department needs and could help open the door to a range of next-generation commercial opportunities.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.