Blue Origin said Sunday that it lost a set of powerpack hardware for its BE-4 engine during a ground test mishap, dealing at least a minor setback to the development of a powerful U.S.-made propulsion system that United Launch Alliance says is the leading candidate to power the first stage of its next-generation Vulcan rocket.

The commercial space company, founded by Amazon.com’s Jeff Bezos, did not disclose details of the test mishap in a tweet announcing the anomaly.

“We lost a set of powerpack test hardware on one of our BE-4 test stands yesterday,” Blue Origin tweeted Sunday. “Not unusual during development.”

Blue Origin tests its engines and rocket hardware at a sprawling ranch owned by Bezos near Van Horn, Texas. In recent weeks, Bezos and Blue Origin officials have hinted that the first full-scale test firing of a BE-4 engine was coming soon.

Two test stands at the West Texas site are available for powerpack testing or full-scale BE-4 engine firings.

The company said it would soon resume testing, following an engineering philosophy aimed at wringing out hardware during extensive testing, instead of a design-focused, software-oriented development approach.

“That’s why we always set up our development programs to be hardware-rich,” Blue Origin tweeted. “Back into testing soon.”

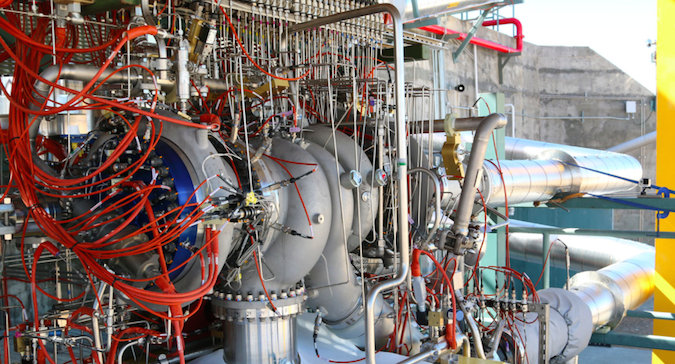

The powerpack includes the turbopumps, valves and other components at the heart of the BE-4 engine. The main turbopump generates 70,000 horsepower from a turbine spinning at 19,000 rpm, pumping cryogenic propellants to pressures of nearly 5,000 psi, according to an email update to Blue Origin followers in March.

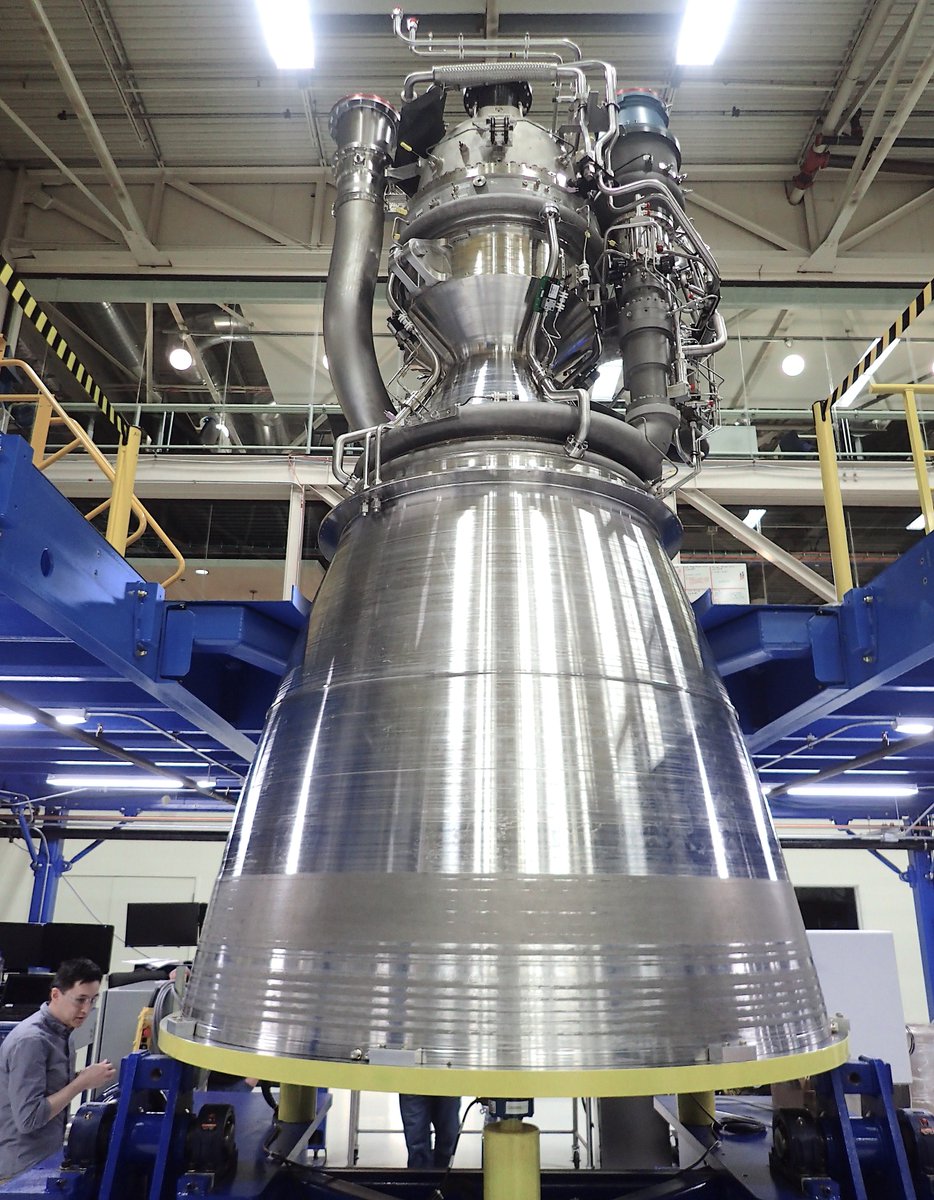

The BE-4 engine is designed to generate up to 550,000 pounds of thrust burning a mixture of liquified natural gas, or methane, and liquid oxygen. It is, by far, the largest methane-fueled rocket engine ever built, a risk factor in ULA’s decision to keep a backup engine option available for its new rocket.

Blue Origin’s huge New Glenn rocket, set for a maiden flight in 2020, will use seven BE-4 engines on its first stage.

Tory Bruno, ULA’s president and CEO, said last month that Blue Origin was ahead of Aerojet Rocketdyne in the development of a new rocket engine, which will eventually replace the Russian-made RD-180 powerplant on the launch firm’s Atlas 5 rocket.

The U.S. government and ULA agreed in 2014 to end reliance on Russian propulsion to launch national security and military satellites. The arrival of SpaceX in the launch market also prompted ULA to move to a lower-cost launcher named the Vulcan, retire most versions of its more expensive Delta 4 rocket next year, and phase out the Atlas 5 in the early 2020s.

Blue Origin’s BE-4 and Aerojet Rocketdyne’s AR1, which burns the same kerosene/liquid oxygen mixture as the RD-180, are the two candidates to power the Vulcan first stage.

Two BE-4 or two AR1 engines, which produce slightly less thrust than the Blue Origin engine, will be mounted to the base of the Vulcan first stage.

Bruno told reporters last month that ULA would make a final selection of the BE-4, in consultation with the U.S. Air Force, once the engine passes an initial round of full-scale hotfire testing in West Texas.

“Whenever you develop a new liquid rocket engine, if you change the fuel, or if you stay with the same fuel and change the scale of the engine, or if you keep the scale, keep the fuel but change the thermodynamic cycle … Any one of those three variables can create a situation we call combustion instability,” Bruno said.

All three variables are new with the BE-4.

“It’s just like if you went out to start your car (in cold weather), you start it up and it idles rough for a few minutes, and then it warms up and everything’s cool,” he said. “That is actually combustion instability in your car’s engine.

“When a rocket engine is sitting there putting out hundreds of thousands of horsepower, those few seconds can tear your engine up,” Bruno said. “So it’s one of the technical issues we deal with in engine development.

“Blue Origin’s engine is methane,” he added. “This will the largest scale we’ve ever done in methane, therefore, combustion instability is an inherent technical risk.”

The first sequence of BE-4 hotfire tests were expected to tell engineers if the engine has any such hiccups at startup.

“It’s not unusual, by the way, to have some instability when you develop a new engine,” Bruno said. “There are tried and true techniques that you apply to smooth that out. If they work right way, you’re usually home free. I’ve never developed an engine that I didn’t have to tune, but I have been in situations where you tried the tried and true things, then nothing works, and nine months later you’re still stuck. That’s the risk we’re retiring here.”

If ground testing goes according to plan, Blue Origin said its BE-4 engine would be flight-qualified by the end of this year, and production engines would be available for launches in 2019. Aerojet Rocketdyne’s schedule calls for the AR1 engine to be certified by 2019, with an initial launch in 2020.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.