SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket climbed into orbit from California’s Central Coast on Saturday, resuming service after an explosive setback last year and delivering much-needed reinforcements to Iridium’s satellite constellation providing communications by land, sea and sky.

The comeback mission kicks off a busy launch manifest with more than 20 SpaceX rocket flights expected this year as the company prepares to start launching astronauts, vital national security payloads and a slate of valuable telecommunications satellites for global broadcasters and network clients.

The 229-foot-tall (70-meter) launcher fired away from Vandenberg Air Force Base, a military complex northwest Los Angeles, at 9:54:39 a.m. PST (12:54:39 p.m. EST; 1754:39 GMT) and soared into a brilliant blue sky, trailing a stream of orange-hot exhaust from nine kerosene-fueled Merlin 1D engines as the booster turned south over the Pacific Ocean.

Two-and-a-half minutes later, the first stage of the Falcon 9 rocket detached and flew back to the ground, steering through the rarefied upper atmosphere with aerodynamic grid fins and periodic bursts of rocket thrust, nailing a vertical propulsive landing on a barge — or “drone ship” — loitering in the Pacific Ocean west of Baja California.

The recovery attempts were billed as experiments when SpaceX first tried them, but Saturday’s touchdown marked the seventh time one of the 15-story first stage boosters has landed intact. SpaceX intends to refurbish and refly the salvaged rockets, beginning as soon as late February with the launch of a communications craft for SES.

Meanwhile, the mission’s primary purpose was the deployment of 10 new-generation voice and data relay spacecraft for Iridium, a provider of global satellite phone, aircraft and ship tracking, and messaging services.

The second stage’s single Merlin engine shut off around nine minutes after blastoff, and the rocket coasted halfway around the planet, passing over Antarctica before reigniting the engine at around T+plus 52 minutes.

The brief three-second maneuver put the rocket into an on-target orbit, SpaceX said. The mission was aiming for a near-circular 388-mile-high (625-kilometer) perch in polar orbit.

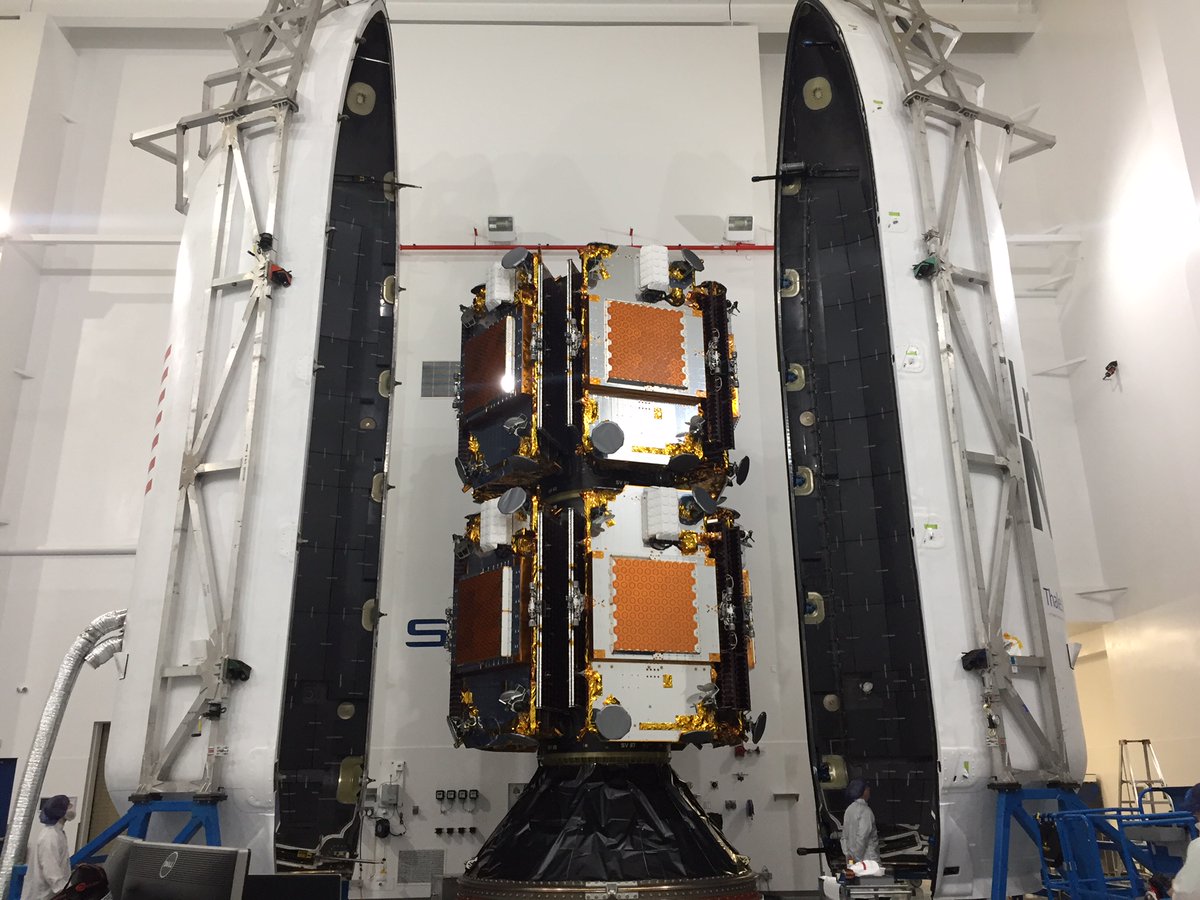

Then came a sequence of 10 critical satellite deployments to release each of the 1,896-pound (860-kilogram) “Iridium Next” spacecraft.

A ground station problem prevented launch control from monitoring the separation maneuvers in real-time, a SpaceX official said, but a few minutes later the rocket flew in range of a tracking site in Svalbard, Norway, transmitting telemetry confirming all 10 satellites were away.

“It’s a clean sweep, 10 for 10,” said John Insprucker, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 product manager. “All the bridge wires show open, and that is a conclusion of the primary mission today, a great one (for the) first stage, second stage, and the customer’s satellites deployed into a good orbit.”

Engineers from Iridium and Thales Alenia Space, the satellites’ prime contractor, verified all 10 relay stations were alive and functioning after their ride to orbit.

That was the moment Iridium chief executive Matt Desch said he would breathe a sigh of relief.

“The real nerves for me is that this is the first time we have deployed our satellites and had them talk to us,” Desch told Spaceflight Now in an interview before the launch. “I know that fear will go down dramatically once we get some satellites in orbit.”

Saturday’s flight was the first of at least seven Falcon 9 flights planned to populate the Iridium fleet with modernized satellites.

The successful launch clears the way for the resumption of SpaceX missions after a rocket exploded on its launch pad at Cape Canaveral on Sept. 1, grounding the Falcon 9 four-and-a-half months.

SpaceX traced the probable cause of the accident to high-pressure helium tanks on the Falcon 9’s upper stage, which are immersed inside super-cold liquid oxygen and wrapped in carbon shell.

Engineers found that voids could form between the aluminum lining of the tanks, which hold cryogenic helium to pressurize the rocket’s propellant system for flight, and the carbon overwrap.

Liquid oxygen trapped in the buckles can ignite, investigators said, and most likely led to the sudden explosion Sept. 1 that destroyed a Falcon 9 rocket and a nearly $200 million satellite during a pre-flight test.

SpaceX said they would alter their countdown procedures on future launches, and no longer conduct such “static fire” tests with satellites on-board.

The launch company is shifting its Florida flights to launch pad 39A, a shuttle-era facility at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, after the Sept. 1 mishap damaged the Falcon 9’s previous pad.

Construction crews are still finishing modifications to pad 39A for Falcon 9 flights and eventual crewed launches, which are planned in partnership with NASA starting in 2018 to carry astronauts to the International Space Station.

The next Falcon 9 mission could take off as soon as Jan. 26 from pad 39A with the EchoStar 23 communications satellite. SpaceX’s next cargo delivery flight to the space station will follow around Feb. 8.

The 10 “Iridium Next” satellites orbited Saturday were designed by Thales Alenia Space in France, and then assembled and tested in an assembly line fashion in partnership with Orbital ATK in Arizona.

Sixty-six are needed to fully replace Iridium’s current constellation, and Iridium ordered 15 more as spares.

“Leading a worldwide team to manufacture, assemble, test and prepare each satellite for this moment has been incredibly exciting,” said Bertrand Maureau, executive vice president of telecommunications at Thales Alenia Space. “We are very proud to have conducted such a unique program, in terms of scale and complexity as well as to have successfully completed the end-to-end whole constellation on-ground validation. The system is fully tested, and the compatibility of Iridium Next with the Block-1 operating satellites has been perfectly demonstrated.”

“We are proud to be a part of this revolutionary satellite program,” said Frank Culbertson, president of Orbital ATK’s space systems group. “Seeing these first ten satellites launch successfully into space is the result of a unique assembly line process at our satellite manufacturing facility that represents a remarkable achievement. We look forward to seeing the innovative solutions these satellites, which are great examples of leading-edge technology and manufacturability, will enable.”

The upgraded network will offer faster broadband connections, improved functionality and 3G-equivalent cellular phone services for Iridium’s pool of nearly 850,000 subscribers, a client list that includes the U.S. military, oil and gas companies, aviation and maritime operators, and mining and construction contractors.

All of the upgraded satellites also carry piggyback payloads for Aireon, an affiliate of Iridium, to help air traffic controllers track airplane movements worldwide. Four of the Iridium Next satellites launched Saturday host an antenna to monitor maritime traffic for exactEarth, a Canadian company, and Harris Corp. of Melbourne, Florida.

Iridium and its contractors will spend around three months wringing out the first set of 10 Iridium Next spacecraft ahead of the launch of the next batch in April, according to Desch.

As more new satellites join the Iridium fleet, engineers will maneuver each one from its 388-mile-high drop-off orbit into the operational constellation at an altitude of 485 miles (780 kilometers) alongside the craft it is intended to replace.

“One-by-one, we’ll do this process called a slot swap, where we move the satellite 50 kilometers (30 miles) from the other satellite — right behind it — and then instantaneously swap over the inter-satellite links between the old satellite and its peers and the new satellite and its peers,” Desch said. “Then we will command the old satellite to deboost and deorbit itself.”

Desch said Iridium’s team used the launch delays for extra testing on the satellites, the ground control system and software to ensure the “slot swaps” go as planned. The ground team has also rehearsed the activity in simulations.

“That whole process is going to go one-by-one 66 times over the next 15 months or so,” Desch said. “It’s an incredibly complicated, highly-choreographed, highly-rehearsed and practiced set of maneuvers that is going to keep us incredibly busy.”

Desch said the successful launch Saturday “only starts our efforts, which, frankly, I think is one of the more complicated things going on in the aerospace industry, and (that’s) probably not well-understood. It’s never been done before on a scale like this, where one network is completely replaced in space. We’ve been using the term ‘tech refresh’ … It’s one of the largest tech refreshes in history.”

The Iridium network relies on satellites spread out in six orbital lanes, each home to 11 active spacecraft, to provide uninterrupted global coverage.

The company’s existing satellites were launched from 1997 through 2002 for missions originally scheduled to least eight years. Nevertheless, Desch said most of the satellites have outlived their design lives, and 64 of the 66 relay stations required for worldwide service remain operational.

Two satellites dropped offline last year, reducing Iridium’s service availability to around 98 percent.

“We need reinforcements to replace the network,” Desch said Friday. “We haven’t lost any other satellites, knock on wood, in at least six months or longer now. The current network is holding up fine. I would expect it will still be able to maintain that high performacne for another two or three years, at least, because the satellites are not showing signs of imminent decline.”

The last satellite to fall out of the Iridium network was running low on fuel, and other members of the fleet have succumbed to electronic failures. One satellite was destroyed in a violent in-space collision with a defunct Russian military satellite in 2009 in an incident infamous in space industry circles.

Battery health remains good across the Iridium fleet, Desch said.

“We still haven’t lost any satellites from battery failures,” he said. “But they’re getting old. Twenty years is a long time for a satellite, and maybe they can make it to 22, 23 or 24 years, but that’s really pushing it on the network.”

The first two Iridium Next launches were slated to target the holes in the network, Desch said.

Saturday’s flight was timed — to the second — to launch into Plane 6 of the constellation, where only 10 satellites remain operational.

The Iridium Next program is a $3 billion investment by Iridium. The purchase of 81 satellites represents approximately $2.2 billion of that cost, Desch said, and the company’s launch contract with SpaceX for seven Falcon 9 flights was valued at $492 million when the parties signed it in 2010.

Desch said Iridium will scale back its capital expenditures once the new-generation fleet is up and running.

“That underpins all of this,” Desch said. “It’s not just a technical marvel that we’re doing, but it’s also a financial transformation that we’re not very far away from, finally, but we’ve got to get these satellites up first.”

Email the author.

If you appreciate articles like this one, help us continue and expand our coverage of the space program by becoming a Spaceflight Now Member.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.