Four days after a picture-perfect blastoff from southern Japan, a cargo-carrying supply freighter arrived at the International Space Station on Tuesday with 4.5 tons of equipment, food, clothing and experiments.

The 33-foot-long (10-meter) H-2 Transfer Vehicle built and operated by Japan approached the space station from below, pausing at predetermined hold points to ensure proper alignment with its flight corridor.

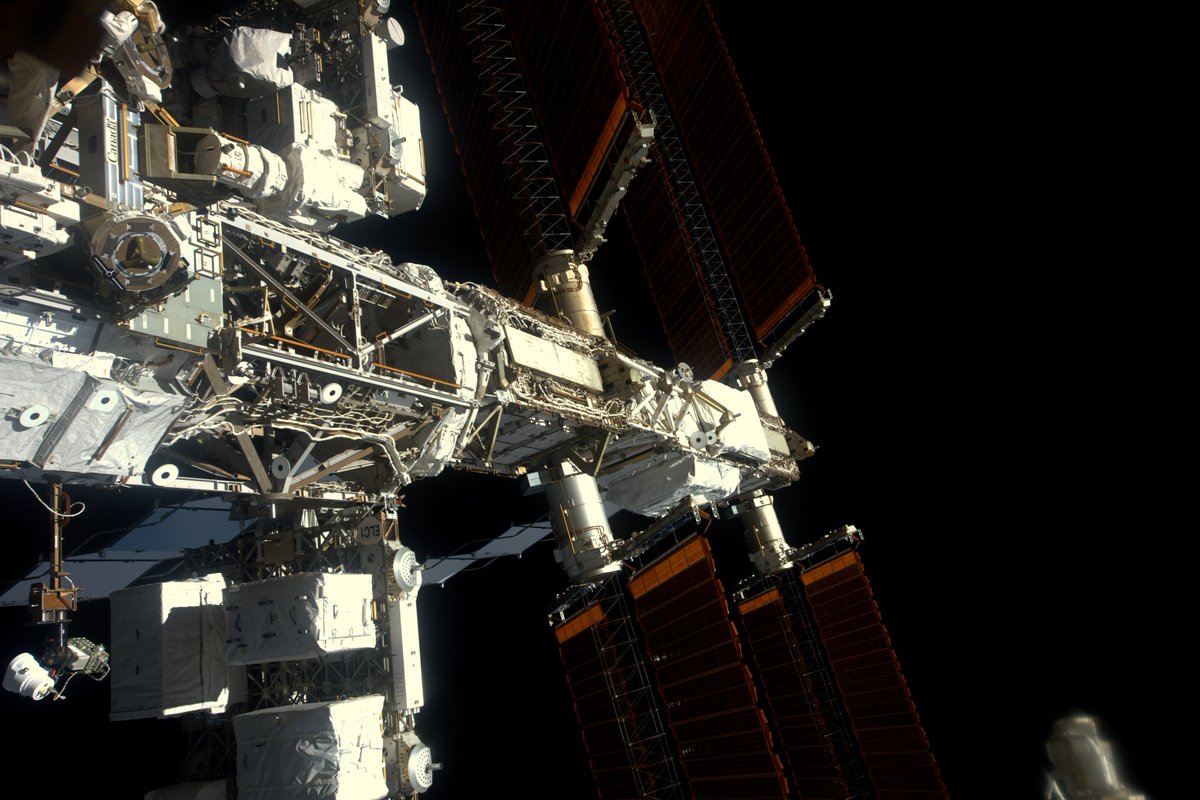

The rendezvous went faster than anticipated, and the HTV supply ship was grappled by the space station’s 58-foot-long (17.6-meter) Canadian-built robotic arm at 1037 GMT (5:37 a.m. EST) as the complex sailed 250 miles (402 kilometers) over southern Chile.

“Houston, station, we see a good capture of the HTV,” radioed astronaut Thomas Pesquet soon after the Japanese supply carrier was in the firm grasp of the station’s robotic arm.

“Copy, we see the same, congrats,” replied astronaut Jessica Meir, spacecraft communicator in mission control.

Shane Kimbrough, the commander of the station’s Expedition 50 crew who was in control of the robot arm Tuesday, chimed in moments later with his congratulations for the HTV ground team.

“It has about four-and-a-half tons of supplies for us, which we’re really excited about,” Kimbrough said.

“We were talking last night and thought it was really cool how our cooperation, and the strength of our international cooperation, is so strong when you have a NASA astronaut and a European Space Agency astronaut using the Canadian robotic arm grabbing a Japanese vehicle and attaching it to the U.S. side of the space station,” Kimbrough said. “That’s pretty cool, so we’re very excited about that.”

Ground controllers took over commanding of the robotic arm soon after Kimbrough captured the cargo craft to maneuver the HTV to a berthing port on the Earth-facing side of the space station’s Harmony module.

Mission control completed installation of the HTV on the space station at 1357 GMT (8:57 a.m. EST), when 16 bolts drove into place to create a firm connection between the supply ship and the Harmony module. Astronauts planned to open hatches leading into the HTV on Wednesday, but that could be moved up to Tuesday evening if the crew has time.

The HTV mission is Japan’s sixth resupply flight to the orbiting research outpost. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency pays its share of the space station’s annual operating costs with cargo delivery services, earning access for Japanese astronauts and research experiments.

Nicknamed Kounotori 6 — the Japanese word for white stork — the logistics freighter is packed with 9,080 pounds (4,119 kilograms) of payloads, according to NASA.

The mission blasted off from Tanegashima Space Center in southern Japan on Dec. 9 on top of an H-2B rocket.

Equipment aboard Kounotori 6 includes hardware for the space station’s life support system. NASA requested the Japanese space agency deliver fresh parts for the space station’s carbon dioxide removal assembly, which scrubs carbon dioxide from the air inside the complex.

Among the science hardware is a payload package designed to demonstrate new spacecraft cooling systems, and a dosimeter to measure radiation exposure inside the space station. A high-definition imager, with 4K and 2K cameras, is also aboard Kounotori 6 to eventually be added to an external mount outside Kibo, enabling better nighttime photography.

The pressurized cargo manifest includes 2,786 pounds (1,264 kilograms) of crew supplies — food, water, clothing and other items — 1,641 pounds (663 kilograms) of vehicle hardware, such as tools and spare parts, 925 pounds (420 kilograms) of research payloads and associated gear, and 343 pounds (156 kilograms) of computer resources.

Ground crews also placed inside Kounotori 6 around 77 pounds (35 kilograms) of spacesuit and spacewalk equipment and 62 pounds (28 kilograms) of cargo for the the station’s Russian segment.

But the items aboard Kounotori 6 that will get the most attention from the station crew are six lithium-ion batteries bolted to a pallet nestled inside the HTV’s unpressurized cargo section.

While astronauts inside the outpost unload the HTV’s pressurized module, the station’s robot arm will pull the pallet out of the spacecraft’s external payload bay to begin the process of replacing batteries on one of the research lab’s solar array truss segments.

The space station has a truss backbone stretching longer than a football field. There are four solar array modules on the ends of the truss, each with solar panel wings measuring around 240 feet (73 meters) tip-to-tip to charge the station’s batteries when in sunlight.

The original nickel-hydrogen batteries are aging, and the replacements that began arriving Tuesday are lighter and more efficient.

“Based on a lot of the equipment thats brought up we’re going to see a lot of robotic and spacewalk activity coming up in the next few weeks, and it’s going to be really exciting,” Kimbrough said. “The vehicle has the new lithium-ion batteries that are going to get installed on the outside of the space station to improve our power system on the space station.

“Again, congrats to our JAXA partners and other members of our international partnership on this really impressive achievement,” he said. “The vehicle is beautiful, and it performed flawlessly.”

The bulk of the battery replacement work will be done using the space station’s Dextre robotic handyman, which has two arms and a toolkit to do tasks that previously required astronauts to go out on spacewalks.

Still, two spacewalks are scheduled for Jan. 6 and Jan. 13 to assist in the battery upgrade.

Kimbrough and astronaut Peggy Whitson will go outside on the first spacewalk, and Kimbrough and Pesquet are assigned to the second excursion.

The robotic part of the battery swap will start New Year’s Eve. The six lithium-ion batteries will go on the station’s S4 starboard-side truss segment, home base for two of the lab’s eight prime power channels.

There are 12 old nickel-hydrogen batteries being replaced on this mission — each new unit has the capacity of two old batteries — and nine of the outgoing batteries will be mounted on the HTV cargo pallet for disposal at the end of the craft’s mission.

The three other disused batteries will go on adapter plates also delivered by Kounotori 6 to be stored outside the station.

Eighteen more lithium-ion batteries are scheduled to head for the space station on the next three HTV missions in 2018, 2019 and 2020.

The new lithium-ion batteries should operate for at least 10 years — longer than the space station’s planned remaining lifetime. Each new unit weighs about 550 pounds (250 kilograms).

The total mass of the battery package, including the adapter plates, is around 3,013 pounds (1,367 kilograms), a NASA spokesperson said.

The next-generation batteries were assembled by Aerojet Rocketdyne with cells supplied by GS Yuasa Lithium Power Inc., a Roswell, Georgia-based subsidiary of GS Yuasa Corp. of Japan. GS Yuasa says it has lithium-ion battery cells on more than 120 government and commercial satellites, including the H-2B rocket and HTV cargo carrier slated to launch the station’s new batteries.

The HTV is the only cargo transporter that can carry a large number of battery units, according to JAXA.

There are 12 CubeSats inside the HTV cargo craft — seven with their launch arranged by JAXA and five by Houston-based NanoRacks — to be ejected into orbit outside the station’s Kibo lab in the coming months.

The CubeSats launched through an arrangement with NanoRacks include the 6-pound (3-kilogram) TechEdSat 5 spacecraft, a mission from NASA’s Ames Research Center to test out an “exo-brake” device to slow down and re-enter Earth’s atmosphere.

NanoRacks’ allotment also includes four Lemur-2 CubeSats from Spire Global, a San Francisco company with a growing fleet of small satellites to track global shipping traffic and collect commercial weather data.

Here is a list of the CubeSats on Japan’s payload manifest, with descriptions offered by JAXA :

- AOBA-Velox 3, from the Kyushu Institute of Technology in Japan and the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, will evaluate the performance of a pulsed plasma thruster

- TuPOD, from the Italian company GAUSS, will attempt deployment of two daughter nanosatellites from Brazilian and U.S. builders

- EGG, from the University of Tokyo, will test the inflation of a torus‐shaped aeroshell for a de-orbit demonstration

- ITF-2, from the University of Tsukuba, will connect amateur radio users

- STARS-C, from Shizuoka University, will attempt to extend a tether between two 1U CubeSats

- FREEDOM, from Nakashimada Engineering Works Ltd. and Tohoku University, will deploy a “film-type” de-orbiting device

- WASEDA-SAT 3, from Waseda University, will also deploy a “film-type” de-orbiting device and project an image onto the film surface using a micro-miniature projector

Once the HTV leaves the station Jan. 20, it will spend another week in orbit conducting an experiment that could lay the foundation for a mechanism to remove space junk from orbit.

The spaceship will unreel a nearly half-mile-long (700-meter) tether, made of strands of thin aluminum and stainless steel wire, once at a safe distance from the space station, and scientists will monitor the device’s deployment and behavior for about seven days.

Space debris experts say electrodynamic tethers like the one carried on Kounotori 6, which has a thin coating of lubricant to encourage electric conductivity, could offer a way to de-orbit derelict rocket stages and aging satellites without expending precious propellants.

The interaction between an electrodynamic tether and the Earth’s magnetic field should generate enough energy to change an object’s orbit, eventually allowing it to burn up in the atmosphere.

Japanese ground controllers will sever the tether after about a week to keep it from interfering with the HTV’s own destructive re-entry, which will be guided by conventional rocket thrusters in a de-orbit burn. The ship will dispose of several tons of space station waste and the decommissioned nickel-hydrogen batteries.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.