China is ready to debut a heavy-lifting rocket rivaling the biggest boosters in the world Thursday, paving the way for a backlog of missions to loft massive space station modules, send deep space probes to the moon and Mars, and perhaps deploy commercial satellites.

The Long March 5 rocket is bigger than anything else in China’s rocket inventory, and it closely matches the capacity of United Launch Alliance’s Delta 4-Heavy rocket, the largest existing rocket in the U.S. fleet.

The launcher is a leap in capability for China’s space program, which sees the Long March 5 as crucial to plans for a permanently-staffed space station, robotic sample return missions to the moon, a Mars rover, and hopes for China to gain a firmer foothold in the commercial launch industry.

China is revamping its Long March rocket family, successfully launching the Long March 6 light-class booster and the medium-lift Long March 7 rocket on inaugural flights in September 2015 and in June, respectively.

The Long March 5, with the power to hoist payloads more than twice as heavy as any other Chinese rocket, will round out the next-generation booster fleet. The new rockets eliminate the use of toxic propellants like hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide, replacing them with more environmentally-friendly kerosene and hydrogen.

Launch crews rolled out the 187-foot-tall (57-meter) rocket Oct. 28 on a mobile launch platform, transferring the Long March 5 to its purpose-built launch pad at Wenchang, a new spaceport built on Hainan Island, just off the southern edge of the Chinese mainland, according to the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology.

Once the Long March 5 arrived at the launch pad, located less than a half-mile (600 meters) from the beach, swinging platforms enclosed the rocket inside the 300-foot-tall (92-meter) gantry to protect the vehicle from the elements.

Technicians planned to conduct final preflight checks on the Long March 5 rocket ahead of its launch, which Chinese authorities have officially only said will occur some time in November.

But a notice to pilots released by Chinese aviation officials late Tuesday indicated the rocket could blast off as soon as Thursday at around 1000 GMT (6 a.m. EDT), or around 6 p.m. Beijing time.

China’s state-run media has not said if they plan any live coverage of the launch.

The rocket is expected to head east over the South China Sea bound for a geostationary-type orbit, but China has not disclosed the targeted flight profile for Thursday’s test launch.

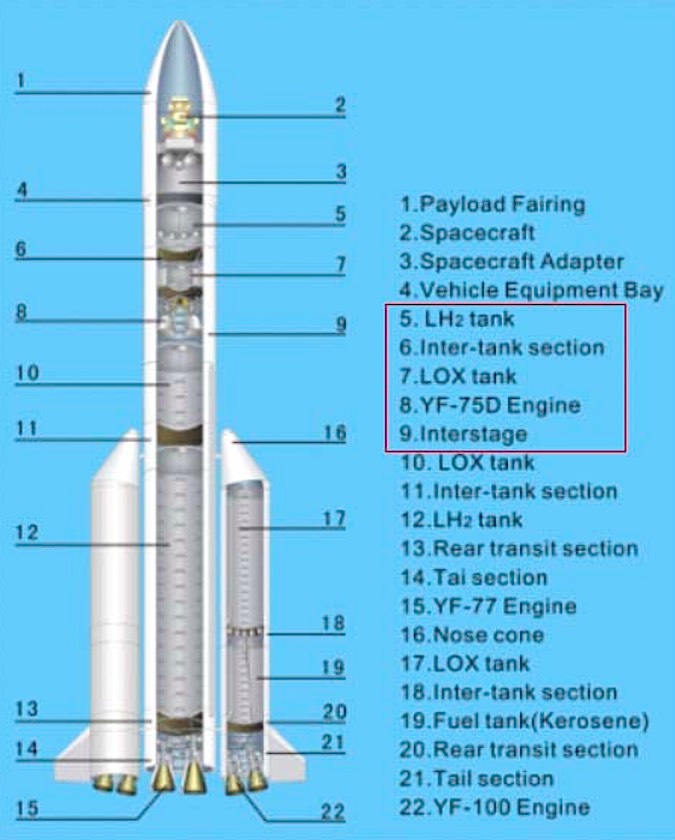

The Long March 5 will lift off powered by 10 liquid-fueled engines mounted at the base of the launcher’s core stage and strap-on boosters. The engines will collectively generate around 2.4 million pounds of thrust at full throttle.

Chinese engineers who designed the Long March 5 clustered four liquid-fueled boosters, each powered by two YF-100 engines, around a core stage fitted with two YF-77 engines, China’s first booster-class rocket engines to burn super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen as propellants.

The YF-100 engine, a more powerful model of Russia’s RD-120 rocket engine, consumes a mixture of rocket-grade kerosene and liquid oxygen. The YF-100 engine can produce up to 270,000 pounds of thrust at sea level.

China acquired several RD-120 engines from Russia in the 1990s, and the YF-100 engine operates with oxygen-rich staged combustion, a closed propulsion cycle that minimizes propellant waste, resulting in a more efficient, but more complex, propulsion system.

The central stage’s two YF-77 engines, connected together with a structural thrust frame, each produce about 115,000 pounds of thrust at ground level, and up to 157,000 pounds of thrust in vacuum. The YF-77 is the largest hydrogen-fueled rocket engine ever built in China.

The YF-77 engines are flying for the first time, while China’s YF-100 engines successfully flew on the country’s Long March 6 and Long March 7 rockets on their maiden launches.

Two YF-75D engines are on the Long March 5’s second stage. The restartable expander cycle YF-75D is the latest upgrade to China’s long line of cryogenic hydrogen-fueled upper stage engines, which first flew on a space mission in 1984.

On Thursday’s launch, the Long March 5’s liquid-fueled boosters should burn for around three minutes before their release to fall into the South China Sea. The YF-77 engines on the core stage are rated to fire for more than eight-and-a-half minutes, according to presentations by Chinese engineers at international aerospace conferences.

Chinese officials have not revealed exact timeline or the orbit to be reached on the Long March 5’s maiden flight, but the rocket may carry a Yuanzheng space tug designed to inject satellites directly into geostationary orbit, a more than 22,000-mile-high (nearly 36,000-kilometer) circular loop around Earth’s equator often used by communications satellites.

An experimental satellite named Shijian 17 is stowed inside the Long March 5’s nose shroud to conduct an electric propulsion demonstration in orbit.

Chinese engineers have studied a heavy-lift booster since the 1990s, and China officially announced plans to develop the Long March 5 in early 2001. Full-scale development of the new YF-77 engine began in 2002.

China broke ground on a new rocket factory for the Long March 5 and Long March 7 in the port city of Tianjin in 2007, when officials hoped to launch the Long March 5 for the first time in 2013.

The maiden flight slipped to 2014, then 2015, before winding up in late 2016.

One of the challenges faced by machinists and engineers was the fabrication of the Long March 5’s large tanks, requiring new tools and techniques to master the precision needed to weld and assemble the rocket’s 16-foot-diameter (5-meter) core, according to state media reports.

The diameter of the Long March 5’s main stage is 50 percent wider than China’s other rockets. Engineers needed to widen the rocket tanks to accommodate a larger load of hydrogen fuel.

China has at least two basic variants of the Long March 5 on the drawing board.

The version selected for the maiden test flight has a second stage for geostationary and interplanetary missions. China says it is capable of delivering a payload of up to 14 metric tons, or nearly 31,000 pounds, to geostationary transfer orbit, nearly identically matching the lift capability of ULA’s Delta 4-Heavy and exceeding that of the European Ariane 5 rocket.

A shorter configuration without the second stage, named the Long March 5B, could place up to 25 metric tons, or 55,000 pounds, into low Earth orbit several hundred miles up, just shy of the Delta 4-Heavy’s capacity to the same orbit.

If Thursday’s test flight goes well, the Long March 5 could be cleared to launch China’s Chang’e 5 robotic moon mission next year to retrieve lunar samples and return them to Earth.

Another Long March 5 mission as soon as 2018 will put the centerpiece of China’s planned space station in low Earth orbit. The Tianhe 1 module will be joined by at least two other research labs to complete the space station by 2022, when it will host astronauts from China, and perhaps Europe and Russia, for six-month stays.

A precursor to the space station named Tiangong 2 is currently in orbit with two Chinese astronauts on-board. The crew is about halfway through a planned 33-day mission.

China is also developing a Mars orbiter and rover scheduled for liftoff on a Long March 5 booster in 2020.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.