Khrunichev and International Launch Services, the team behind Russia’s Proton rocket, are developing two scaled-down versions of the booster in a bid to capture a wider share of the commercial launch market, the companies announced last week.

The “Proton Medium” and “Proton Light” rocket variants could launch as soon as 2018 and 2019, respectively, to carry lighter satellites into orbit at lower cost, ILS said.

The new configurations are “right-sized” for the current launch market, according to Kirk Pysher, president of ILS, as some commercial communications satellites are getting smaller with the introduction of innovations like all-electric propulsion, which does away with the need to put hefty liquid fuel loads on spacecraft.

“Currently, Proton is focused strictly on the heavy-lift market, where we are highly competitive,” Pysher said. “The Proton variants will provide (a) diverse launch capability for the customer with a two-stage launch vehicle that provides a very elegant solution to diversifying our capability across the small and medium-class payload mass.”

The basic Proton booster comes in three stages. For commercial missions, the Proton is topped by a payload shroud containing the mission’s satellite payload and a Breeze M upper stage that conducts multiple engine firings to place spacecraft into their proper orbits.

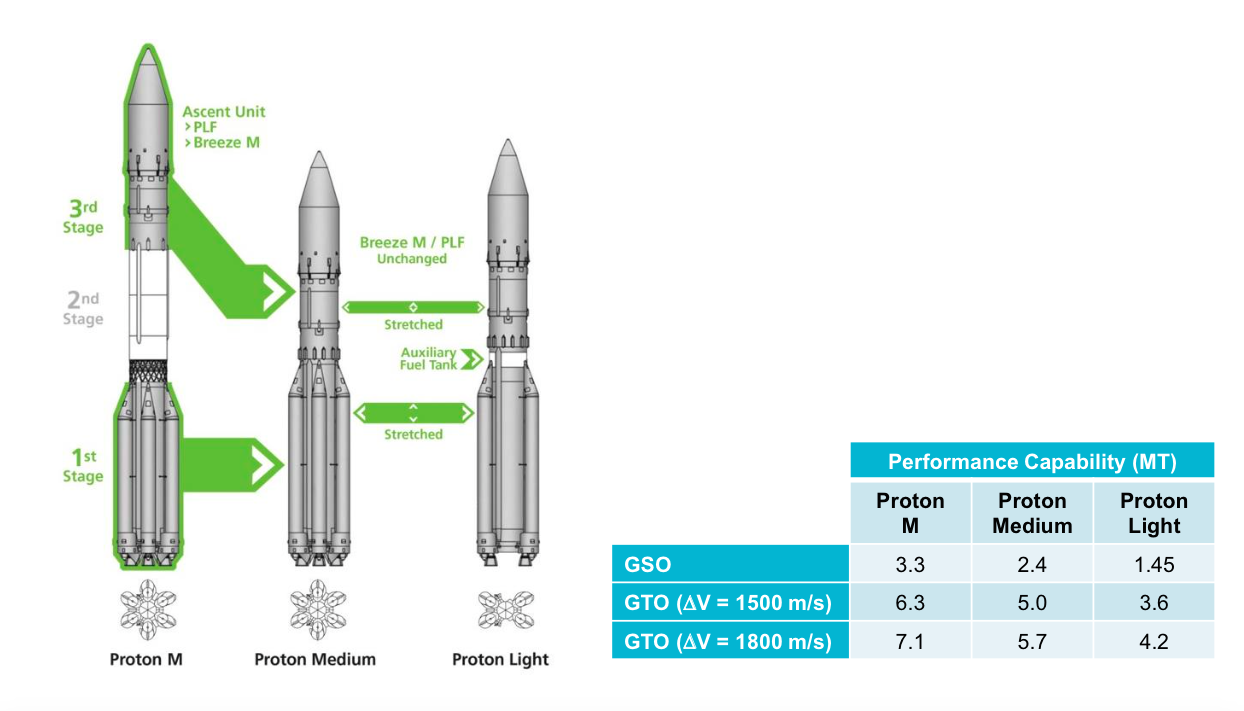

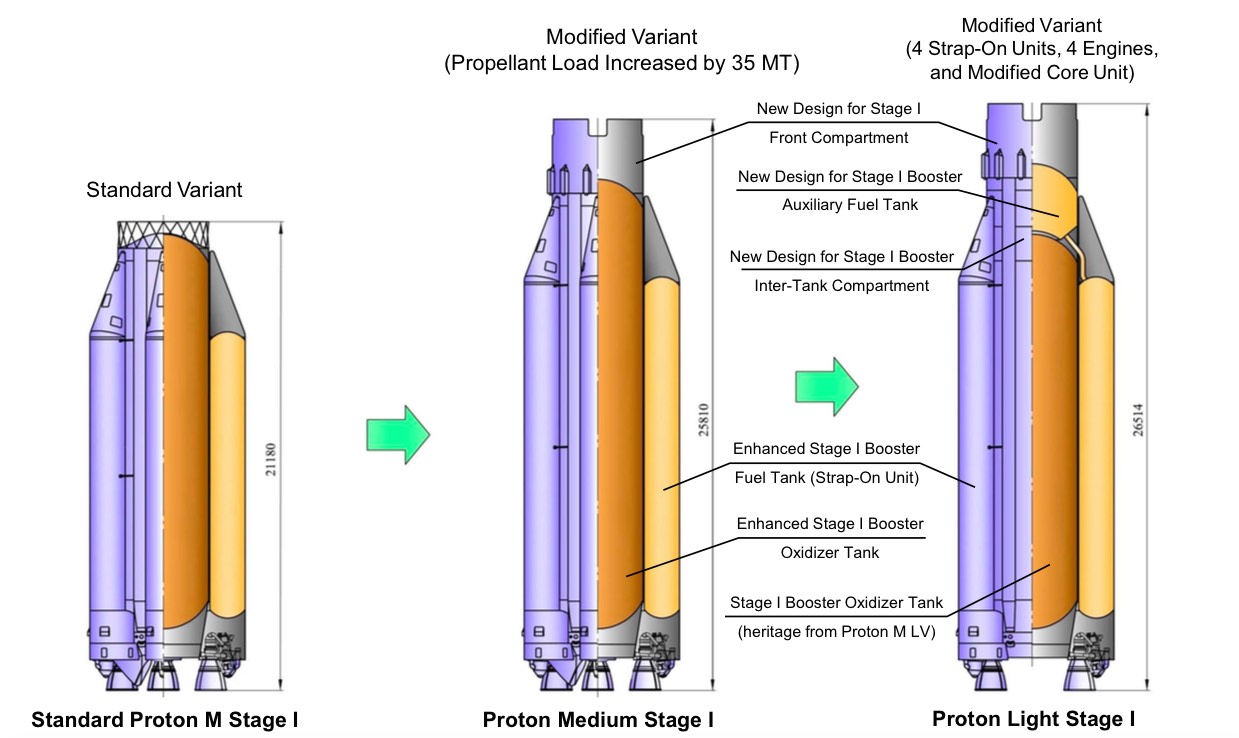

The new versions unveiled last week by ILS and Khrunichev both do away with the second stage and its four engines. The new designs have the Proton’s third stage, powered by a single main engine and four steering thrusters, mounted directly on top of the first stage.

“The first thing we decided to do is eliminate the second stage of the three-stage Proton vehicle,” said Jim Kramer, ILS vice president of engineering and mission assurance. “We then addressed the rest of the systems to have a minimum impact for the operation of the vehicle and meet our performance targets.”

Engineers avoided tinkering with the Proton’s avionics, guidance, navigation, and control, and propulsion systems.

Propellant tanks inside the Proton’s existing first and third stage components will be lengthened to accommodate more fuel in the new two-stage variants. The Breeze M upper stage and payload fairing will remain the same, Kramer said.

“The objective is to take the existing elements, processing and production of the current Proton vehicle, and determine how do we best (meet) these requirements, reduce the basic cost of the rocket, and implement the design reliably while we’re doing it, and have an optimum design that addresses both the three metric ton and five metric ton performance range of the commercial launch market,” Kramer said.

The Proton Medium configuration will retain the six-engine first stage currently flown on Proton missions. A Proton Light variant will have two of the six RD-276 engines removed and launch with four first stage powerplants.

“With the Proton Light vehicle, we take that basic design of the Proton Medium, (and) we remove two of the six booster engines with their associated fuel tanks,” Kramer said. “To retain the existing mixture ratio of the booster engines, we are adding an auxiliary fuel tank above the oxidizer core tank in the first stage to provide additional fuel to the four strap-on tanks.”

According to documents released by ILS to Spaceflight Now, the Proton Medium can loft up to 5 metric tons (about 11,000 pounds) into a standard geosynchronous transfer orbit, a trajectory that extends more than 35,700 kilometers (22,200 miles) above Earth favored by communications satellite owners with payloads heading for operating posts over the equator.

Proton Light’s performance target to geosynchronous transfer orbit is around 3.6 metric tons (7,900 pounds), according to ILS.

For comparison, the existing Proton rocket can deploy a payload of more than 6.3 metric tons (nearly 13,900 pounds) to the same target orbit, which requires the satellite’s own thrusters to make up about 1,500 meters per second (3,355 mph) of velocity to circularize its orbit at geostationary altitude over the equator.

Pysher said Krunichev, the Russian builder of the Proton/Breeze M and owner of Virginia-based ILS, will produce the Proton Medium and Proton Light versions exclusively for commercial use by ILS.

“We are able to provide additional oversight and insight to our commercial customers and also optimize the cost of the vehicles,” Pysher said.

An ILS spokesperson said the company is not ready to announce any firm launch contracts for the new Proton variants.

Andrey Kalinovskiy, Khrunichev director general, said the new Proton variants “will complement other launch service providers’ offerings to allow additional access to space for global operators, while increasing the addressable commercial market for Proton.”

The Proton’s current capacity puts it in direct competition — at least in performance class — with the Ariane 5 rocket, which carries up two commercial satellites at a time on most missions, usually a larger spacecraft around 6 metric tons in mass and a smaller one between 3 and 4 metric tons.

The larger satellite on dual-payload Ariane 5 missions is usually about the right size to fly on the existing Proton.

If the Proton Medium and Proton Light prove cost-effective and reliable, they will fall in the performance envelope of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket, which takes a performance hit by reserving some first stage propellants for propulsive landings and potential reuse.

“Since this new product line is essentially a commercial offspring of Proton Breeze M, Khrunichev is able to optimize the design, production and operational efficiencies and transfer those savings on to our customers,” Kalinovskiy said in a statement.

Coupled with Russia’s new Angara 1.2 light-class booster now on the market for commercial missions, the new Proton variants give ILS a full range of offerings from low-mass Earth observation satellites flying in low Earth orbit to heavy broadcast platforms destined to fly thousands of miles above the planet.

The Proton will be replaced by Russia’s new Angara A5 rocket, but that vehicle will not enter commercial service until at least 2025.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.