Two pioneering communications satellites purely powered by plasma rocket thrusters lifted off from Cape Canaveral aboard a Falcon 9 launcher Wednesday, starting missions to broadcast video across Asia and Latin America, and improve navigation for airplanes crossing the United States.

The rocket’s first stage booster, a recoverable 15-story vehicle SpaceX hoped to reuse, crashed on landing aboard a mobile platform stationed in the Atlantic Ocean about 420 miles (680 kilometers) east of Florida’s Space Coast, missing the flight’s experimental secondary objective.

But the purpose of Wednesday’s flight was the deployment of two commercial communications spacecraft for Eutelsat and Asia Broadcast Satellite, and the on-target dual-satellite delivery gives SpaceX six successful flights so far this year, matching the company’s annual best.

The 229-foot-tall (70-meter) Falcon 9 rocket thundered away from Cape Canaveral’s Complex 40 launch pad at 10:29 a.m. EDT (1429 GMT) Wednesday, clearing the facility’s four lightning protection masts in less than eight seconds and breaking the sound barrier a little over a minute after liftoff.

Firing on an easterly path from the Central Florida spaceport, the Falcon 9 climbed through scattered clouds atop 1.5 million pounds of thrust and released its first stage about two-and-a-half minutes into the flight.

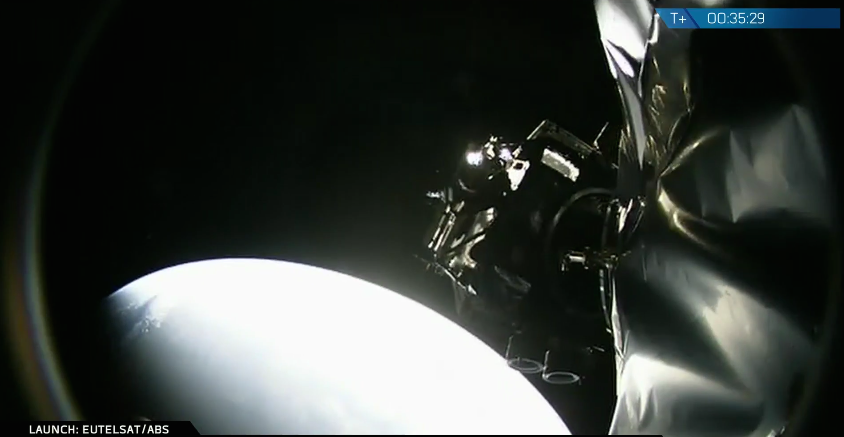

Video cameras fastened to the first stage showed the Falcon 9’s second stage igniting and dramatically accelerating into the inky blackness of space, as the core booster extended four aerodynamic steering fins and began maneuvers to descend toward a landing ship.

The single-engine upper stage burned more than six minutes to place the Eutelsat 117 West B and ABS 2A video relay satellites into a preliminary orbit just as the first stage touched down on SpaceX’s barge.

A live webcast feed from the landing platform, or drone ship, froze as the rocket arrived, showing the booster enshrouded by a plume of fire and smoke.

SpaceX chief executive Elon Musk confirmed the rocket was lost on impact with the drone ship a few minutes later.

“Ascent phase & satellites look good, but booster rocket had a RUD on droneship,” Musk tweeted.

RUD means Rapid Unscheduled Disassembly, a colloquial term in the rocket business.

He added that the thrust level in one of the three Merlin engines used for the final propulsive landing burn was lower than expected.

Looks like thrust was low on 1 of 3 landing engines. High g landings v sensitive to all engines operating at max.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) June 15, 2016

Wednesday’s launch went into a high-altitude “supersynchronous” transfer orbit stretching tens of thousands of miles above Earth, requiring the first stage to reach tremendous speeds of more than 5,000 mph, or about 8,000 kilometers per hour.

For such high-speed missions, the rocket needs all the thrust it can get from the three landing engines to brake for touchdown, Musk said, adding that SpaceX plans to introduce an upgrade to the booster to compensate for a thrust shortfall during the final landing burn by the end of the year.

The missed landing comes after three smooth booster recoveries in a row after the last three Falcon 9 launches April 8, May 6 and May 27.

“We had a successful launch,” a SpaceX engineer said on the company’s live launch webcast. “We did not have a successful landing, unfortunately. Again, this is all experimental. We’re very excited for the day when it becomes regular. But clearly, we’re not quite there yet.”

Musk said SpaceX will release video of the landing attempt after the recovery team gains access to cameras on the barge later Wednesday. “Maybe hardest impact to date,” he tweeted. “Droneship still ok.”

As SpaceX sorted out what happened to the booster, the Falcon 9’s upper stage trekked across the Atlantic Ocean, passing over the Canary Islands and the west coast of Africa before re-igniting its engine for a 64-second firing to send the Eutelsat and ABS spacecraft into their targeted egg-shaped transfer orbit.

The two Boeing-built satellites separated from the Falcon 9’s second stage at five-minute intervals at T+plus 30 minutes and T+plus 35 minutes.

Officials from SpaceX and a customer representative confirmed the spacecraft reached their intended orbit. Boeing later said ground controllers were in contact with both satellites, verifying their health after the fiery journey into space.

Tracking data released by the U.S. military’s Joint Space Operations Center indicated the rocket deployed the satellites in a “supersynchronous” transfer orbit ranging up to 39,000 miles (62,759 kilometers) at peak altitude. The low point of the orbit is less than 250 miles (400 kilometers) above Earth, and the satellites are flying at an angle of 24.7 degrees to the equator.

Driven by low-thrust, high-efficiency plasma thrusters, the spacecraft will slowly reshape their orbits in the coming months to reach a circular perch nearly 22,300 miles (about 35,786 kilometers) over the equator, where their speeds will match the rate of Earth’s rotation, causing the satellites to hover over fixed locations.

Communications satellites with traditional liquid rocket propellant take a few weeks to reach their final positions, but some telecom spacecraft carry more than 5,000 pounds (up to 2,300 kilograms) of fuel to feed their rocket engines.

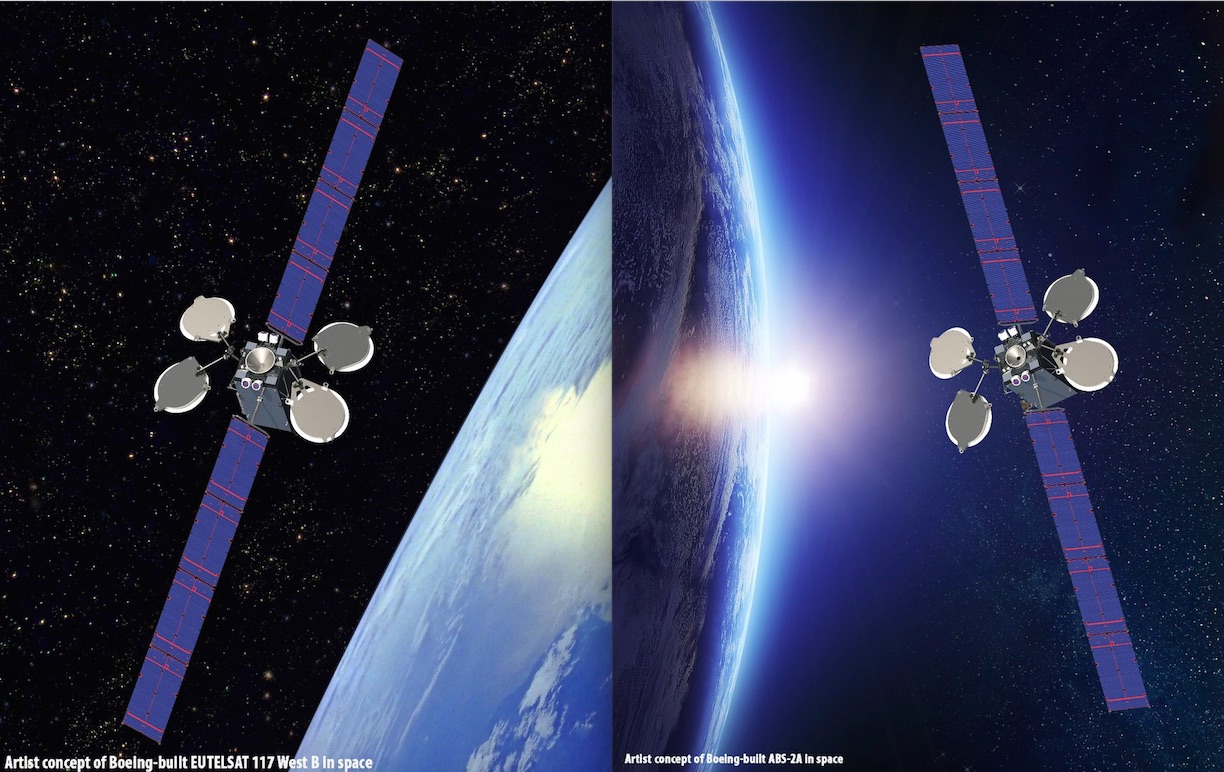

Instead of a large fuel tank, the all-electric satellites — based on the Boeing 702SP design — carry small reservoirs of xenon fuel for its four ion engines, which work by blasting the gaseous propellant with electricity to ionize the fuel and push it out the thrusters at high speed.

The engines produce a whisper of thrust — about the force of a sheet of paper held in your hand — but can operate for months, burning a fraction of the fuel consumed by conventional engines.

Asia Broadcast Satellite and Satmex, a defunct Mexican satellite operator acquired by Eutelsat in 2014, purchased four all-electric spacecraft from Boeing in 2012, and selected SpaceX to launch the payloads.

Without a large liquid fuel tank, the satellites can fit together inside the Falcon 9 rocket’s nose cone and are well within the launcher’s weight capacity.

The Eutelsat 117 West B satellite, which flew in the upper position on Wednesday’s launch, weighed about 4,327 pounds (1,963 kilograms) at liftoff, according to Eutelsat. The ABS 2A satellite riding below is a few hundred pounds heavier, with extra structural stiffeners to take the load of the spacecraft mounted on top.

Unlike other dual-satellite missions, the spacecraft launched directly connected to each other without the need for a special adapter, which would take up more space and weight. Boeing has patented its design of the load-bearing two-satellite stack.

The first two all-electric satellites ordered by ABS and Eutelsat launched in March 2015, and they entered service late last year. The arrangement of the satellites on Wednesday’s launch flipped from the configuration on last year’s mission, which had the ABS payload slotted in the upper position on the Falcon 9 rocket.

A spokesperson for Paris-based said the Eutelsat 117 West B satellite will take about 200 days to steer into its operational orbit, beginning around June 18. The orbit-raising plan for ABS 2A will take about a month longer because of its bigger mass.

While ABS and Eutelsat must wait longer than normal to yield revenue from the newly-launched satellites, the tradeoff is that the all-electric spacecraft design allows a significant reduction in launch costs. Each company paid about $30 million to share the Falcon 9 ride, about half of the cost of a dedicated launch.

Without sizable mass allocated to fuel, engineers can also add more communications capacity to all-electric satellites.

The Eutelsat and ABS satellites each cost approximately $100 million, officials said.

The two craft will unfurl their power-generating solar panels soon after launch, and extend their antennas during the cruise to geostationary orbit.

Both satellites should begin commercial service in early 2017, commencing 15-year missions.

Eutelsat 117 West B’s operating post will be along the equator at 116.8 degrees west longitude, where it will join a sister spacecraft launched in 2013.

“Equipped with 48 Ku-band transponders, Eutelsat 117 West B’s four distinct regional beams will provide premium coverage of Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, South America and the Southern Cone,” Eutelsat said in a statement. “The satellite will strengthen video capacities at 117 degrees west and offer key services to telecom operators and government service providers in Latin America.”

The spacecraft’s capabilities will also serve the direct broadcast market in Latin America, Eutelsat said. It is the fourth Eutelsat satellite launched since December 2015.

Eutelsat 117 West B also hosts a navigation beacon for the Federal Aviation Administration, adding a replacement node to a fleet of GPS augmentation payloads carried by commercial satellites in geostationary orbit.

Made by Raytheon, the Wide Area Augmentation System payload will help improve GPS navigation accuracy from about 30 feet (10 meters) to as little as 3 feet (1 meter). The network allows air traffic controllers to assign more direct flight paths, and reduces separation distances required between aircraft in flight.

The ABS 2A satellite also features 48 Ku-band transponders to serve customers in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Russia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East and North Africa, according to ABS. Parked in geostationary orbit at 75 degrees east longitude, the craft will broadcast direct-to-home television services, and support mobile communications clients.

It will be located near the ABS 2 satellite launched aboard an Ariane 5 rocket in February 2014.

SpaceX’s next launch is set for July 16, when a Falcon 9 rocket will dispatch a Dragon supply ship to the International Space Station. The company plans its second landing attempt on land a few minutes after that liftoff.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.