The first piloted test flight of Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner commercial crew capsule has been delayed to early 2018 as designers wrestle with the mass of the spacecraft, aerodynamic loads the vehicle will see during launch, and new software requirements levied by NASA, company officials said.

Boeing hoped to launch the first CST-100 Starliner with astronauts by the end of 2017.

The delay is evidence of cramped schedules faced by both of NASA’s commercial crew transportation contractors — Boeing and SpaceX — to finish development of new human-rated space capsules and end U.S. reliance on Russian Soyuz vehicles to ferry crews to and from the International Space Station.

Representatives from both companies previously acknowledged schedules were tight to launch astronauts by the end of 2017, with design reviews, structural testing, and abort tests planned in quick succession over the next 18 months.

Boeing now says the CST-100 Starliner will not be ready to carry a crew into space until 2018, with the craft’s first flight with astronauts rescheduled for February 2018, according to Rebecca Regan, a Boeing spokesperson.

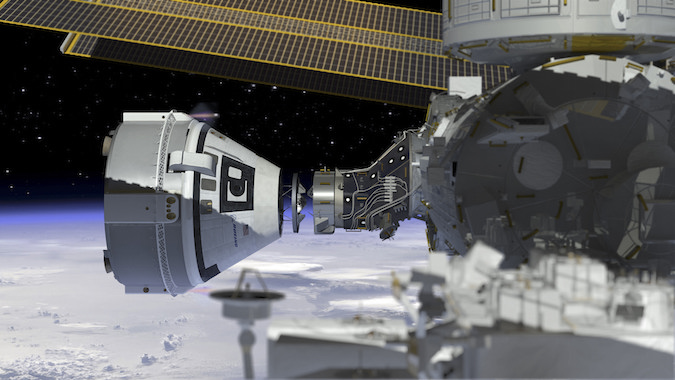

A two-person crew will fly to the space station aboard the CST-100 Starliner a few months after the spacecraft takes off on its first test flight.

Regan said Thursday that Boeing recently presented NASA with an updated schedule for CST-100 Starliner flight tests. That schedule shows an uncrewed test flight to the International Space Station in December 2017 and a piloted demonstration mission in February 2018.

As of March, Boeing planned those missions in June and October 2017, according to schedule documents presented by NASA officials to the agency’s advisory council.

A test of the CST-100 Starliner’s pusher abort engines is now set for October 2017, a couple of months later than previously planned.

John Elbon, vice president and general manager of Boeing’s space exploration division, told Spaceflight Now last month that launching a crew aboard the CST-100 Starliner by the end of 2017 was still “doable.”

But he said Boeing encountered problems with the capsule’s mass and the aero-acoustic pressures the spacecraft will experience during launch on top of United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5 rocket.

“We’ve been working some challenges with mass and with the aerodynamic loads on the vehicle, and we seem to have good solutions for those now,” Elbon said.

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of our full interview with John Elbon. Become a member today and support our coverage.

He added that Boeing and ULA engineers conducted wind tunnel tests to try alternative designs to overcome the aero-acoustic issue and verify the Atlas 5 and CST-100 are compatible.

The CST-100 will launch on a version of the Atlas 5 with a dual-engine Centaur upper stage and two solid rocket boosters. The upgraded Centaur stage, powered by two RL10 engines, has never flown on the Atlas 5 before, and the crew capsule’s launches will be the first time ULA’s workhorse launcher has flown without an aerodynamic shield on its nose.

“Mass is just about scrubbing things and making them lighter,” Elbon said. “Every aerospace vehicle in general faces mass challenges.”

Regan confirmed those two challenges were partly responsible for the CST-100 schedule delay, along with a new software requirement levied by NASA to permit the capsule to dock with the space station. That single issue added three months to the schedule, she said.

Boeing first announced the updated CST-100 Starliner schedule Wednesday, when Leanne Caret, president and CEO of Boeing’s defense, space and security business unit, said the company is working toward the capsule’s first unmanned flight in 2017, followed by a crewed mission in 2018.

Elbon said Boeing has a series of crucial tests planned for the coming months for the CST-100 Starliner.

“Developing a vehicle to carry humans into space, if done properly so they end up with a safe reliable vehicle, is always a steep climb,” Elbon said.

“Just to underscore that, we’ve got about 90 qualification tests starting over the next two months,” he said in April. “Qualification tests are when we take a particular component and put it through its rigors of environments, vibration and temperature, etc. That’s always a critical part of the development program, getting through that season of qualification testing.”

NASA awarded Boeing and SpaceX contracts worth $4.2 billion and $2.6 billion, respectively, in September 2014 to design, test and fly commercially-owned spacecraft to transport astronauts to and from the space station.

The space agency originally hoped to have commercial crew operators flying astronauts this year, but funding shortfalls in Congress forced a two-year delay.

SpaceX still expects to launch its first “Crew Dragon” capsule with astronauts by the end of 2017, with an unoccupied test launch on a Falcon 9 rocket in May 2017, followed by a crewed demo mission as soon as August 2017, according to a NASA schedule.

Working inside a converted space shuttle hangar at the Kennedy Space Center, Boeing technicians are nearing completion of a CST-100 structural test article.

Workers connected the two main sections of the first CST-100 Starliner hull May 2.

“Identical to the operational Starliners Boeing plans to build and fly in partnership with NASA’s commercial crew program, the structural test article is not meant to ever fly in space but rather to prove the manufacturing methods and overall ability of the spacecraft to handle the demands of spaceflight carrying astronauts to the International Space Station,” NASA wrote in a status update on the assembly of the capsule.

The test capsule will soon be shipped across the country to Huntington Beach, California, where engineers will subject it to the stresses of spaceflight.

In the meantime, the lower dome of the first flight-worthy CST-100 Starliner arrived at the Florida assembly center this week. It will be joined by the upper dome of the first space-bound capsule soon, Regan said.

Boeing plans to staff the piloted CST-100 shakedown mission with a company test pilot and a NASA astronaut.

Once SpaceX and Boeing complete their crewed flight tests, NASA will certify each company to launch astronauts on regular crew rotation missions to the space station. The contracts call for each firm to receive orders for up to six “post-certification” missions with four astronauts aboard each flight.

The CST-100 Starliner and Crew Dragon capsules will remain at the space station up to 210 days, offering a lifeboat to whisk the research lab’s crew home in an emergency.

At the end of a normal mission, astronauts will board the CST-100 Starliner to return to Earth with parachutes to an airbag-cushioned landing in the Western United States. The likely landing zones for the capsule’s initial flights will be in New Mexico or Utah, officials said.

Boeing plans to refurbish the reusable capsules to each fly up to 10 times.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.