The maker of inflatable technology for a commercial space station will use a top-of-the-line Atlas 5 rocket with a stretched nose cone to hoist the first habitat into Earth orbit in 2020.

Bigelow Aerospace and United Launch Alliance announced the partnership today at the 32nd Space Symposium in Colorado Springs.

“We could not be more pleased than to partner with Bigelow Aerospace and reserve a launch slot on our manifest for this revolutionary mission,” said Tory Bruno, ULA president and CEO.

“This innovative and game-changing advance will dramatically increase opportunities for space research in fields like materials, medicine and biology. And it enables destinations in space for countries, corporations and even individuals far beyond what is available today, effectively democratizing space. We can’t begin to imagine the future potential of affordable real estate in space.”

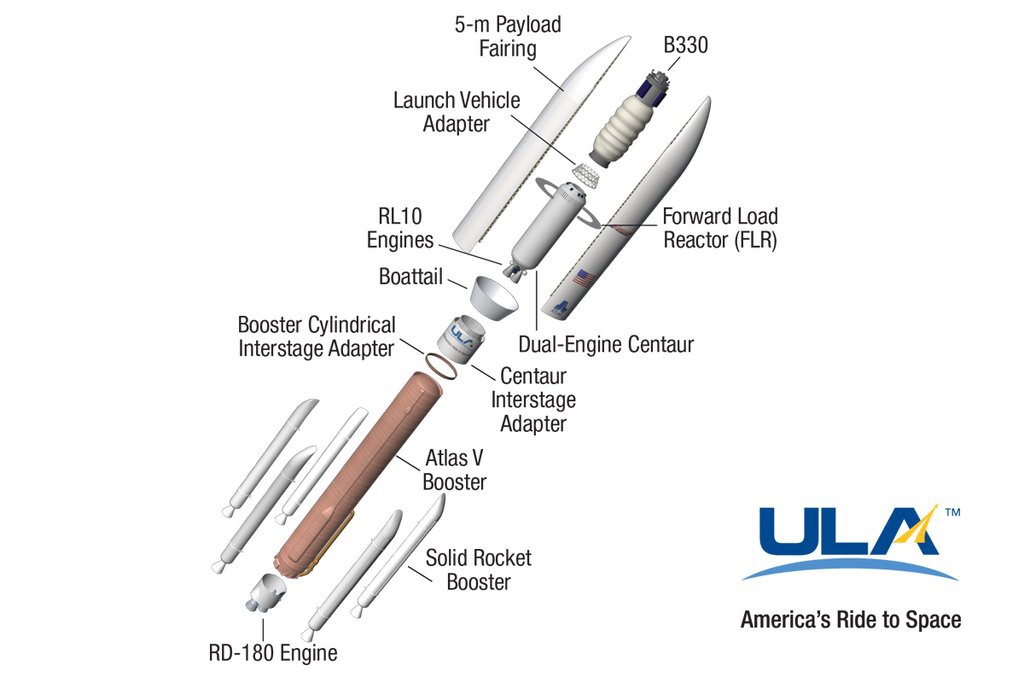

The Atlas 5 rocket will fly in the 552 configuration with five side-mounted solid boosters, a twin-engine Centaur upper stage and an 87-foot-long, 18-foot-diameter payload fairing with over 50 feet of usable cargo room, the most capable variant of the vehicle available.

The longer nose cone will give the vehicle a height of 216 feet, 10 feet taller than any previous Atlas thus far.

“You are constrained by the ability of your launch vehicle. In our case, we have to fit within two things — a vehicle that can lift 43,500 pounds and a vehicle that has the fairing length. There is only one at the moment, and for the next foreseeable few years, and that happens to be the Atlas 552 stretch fairing,” said company founder and hotel entrepreneur Robert Bigelow.

“When looking for a vehicle to launch our large, unique spacecraft, ULA provides a heritage of solid mission success, schedule certainty and a cost effective solution,” he added.

“SpaceX, they do not have the capability with the fairing size that is necessary to accommodate the 330 (module). So that is not even a choice.”

Atlas comes off the pad riding two-and-a-half million pounds of thrust from the solids and its kerosene-fueled main engine. The rocket, which will return to dual-engine Centaurs for greater lifting power on low-Earth orbit ascents starting next year, will have an upper stage with two hydrogen-fed powerplants for 46,000 pounds of thrust.

That performance is needed to lift the so-called “B330” module to space for either a free-flying station or docking it to the International Space Station and increase the existing work and living area there.

“We are exploring options for the location of the initial B330 including discussions with NASA on the possibility of attaching it to the International Space Station,” said Bigelow, the billionaire owner of the Budget Suites of America hotel chain.

.

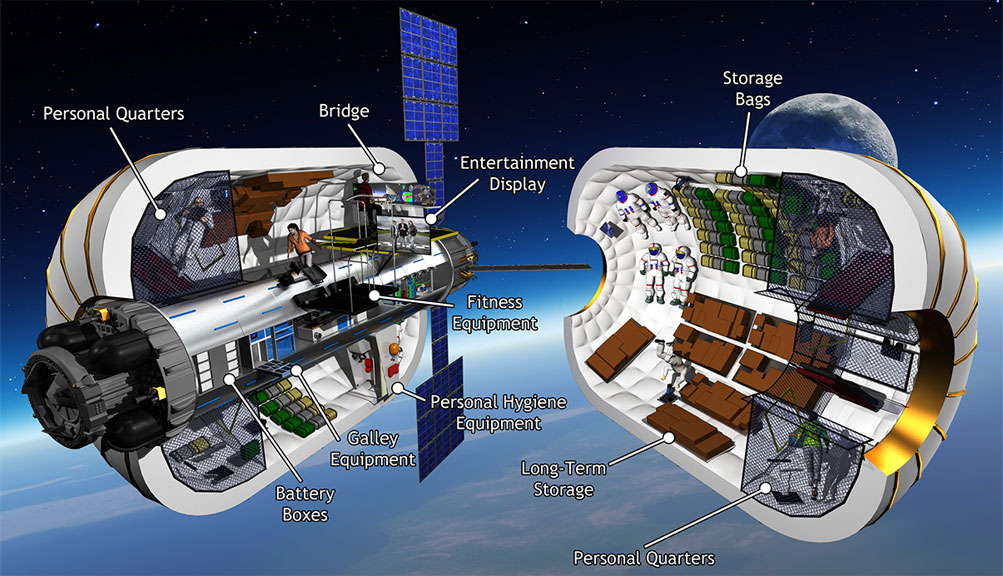

“In that configuration, the B330 will enlarge the station’s volume by 30 percent and function as a multipurpose testbed in support of NASA’s exploration goals as well as provide significant commercial opportunities.”

The provisional name of this module is XBASE or Expandable Bigelow Advanced Station Enhancement.

But if the International Space Station idea doesn’t pan out, Bigelow says “the B330 is essentially a standalone space station in and of itself.”

Commercial uses could range from pharmaceutical research and manufacturing to tourism.

“My background is development, construction, general contracting and banking and everything to do with real estate. So I transfer a lot of the business case from that industry and, essentially, the foundation of our business case (for Bigelow Aerospace) is time sharing. Time sharing time and volume and branding — naming rights to all kinds of advertising,” said Bigelow.

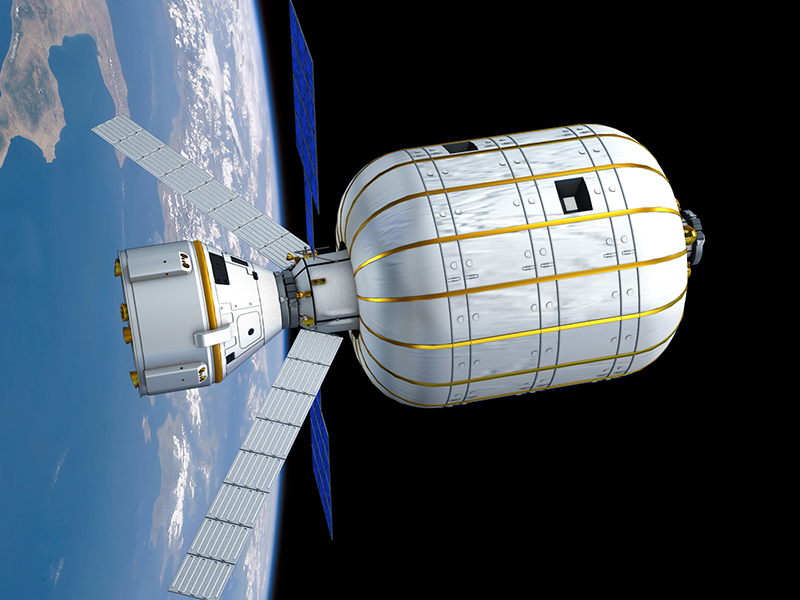

Expandable modules are large, roomy habitats that are lighter to launch and collapse down to fit within the nose cone volume of existing rockets, offering clear advantages over traditional solid-body compartments.

The ULA launch deal comes just one day after Bigelow’s experimental BEAM module — the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module — arrived at the International Space Station aboard a SpaceX cargo-delivery ship. BEAM will be attached to the station this weekend, then inflated in late May for a two-year test to record internal temperatures, reactions to debris impacts and the radiation levels in the module.

“We want to understand the structural integrity, the radiation performance of (the module) and the temperature controls in order to help inform our choices for deep space habitats,” said Jason Crusan, director of NASA’s Advanced Exploration Systems Division. “So we’re going to do that over these two years.”

With the internal volume about the size of a small bedroom, the BEAM module is not equipped with lights or any other crew amenities. The astronauts will keep the experiment compartment closed off and enter only a few times per year to retrieve stored data.

“This type of architecture has never been flown before,” Bigelow said.

“We are in the early phase of a new kind of spacecraft that offers a lot of promise.”

The B330 that Atlas will launch into low-Earth orbit in 2020 will have 330 cubic meters (12,000 cubic feet) of internal space, offering a 210 percent more habitable volume with an increase of only 33 percent in mass compared to the conventional U.S. Destiny laboratory module of the International Space Station.

Built at the Bigelow Aerospace factory in North Las Vegas, each B330 will support a crew of six, have four observation windows and a 20-year design life.

A free-flying Bigelow station could share room between companies and foreign nations wanting to exploit space.

“It’s a combination of everything from what you could manufacture product-wise and bring down,” Bigelow said.

“We would operate these on behalf of nations that have astronaut corps and others that aspire to have them. Right now, the frequency of the opportunity to fly is not often. Other than for the United States and Russia, it’s about once every three years. Some countries, maybe never, or very, very seldom. So there is a substantial appetite out there we’ve discovered, and so we think that’s a market,” Bigelow said.

“It could change the image of a country overnight to have that kind of facility. Or it could induce (a company) to locate their plant in their country and offer them that kind of resource in orbit as a very unique laboratory.”

A commercial mode of transportation for launching crews to the Bigelow facilities and returning them to Earth has stymied the billionaire’s dreams. But with Boeing’s Starliner and the SpaceX Dragon capsules both slated for human test-flights next year, Bigelow’s wait may soon be over.

“The element of substantial cliental — us starting to collect deposits by virtue of reservations — has always been hostage to the availability of transportation. And we’ve had to throttle our own progress according to the ability of transportation to be there at a certain point in time,” Bigelow said.

The Starliners will be delivered to space atop Atlas 5 rockets in the 422 configuration with two solids and twin-engine upper stages. SpaceX will use its standardized Falcon 9 rocket.

The DreamChaser mini spaceplanes and Blue Origin’s orbital vehicle are future options as well, Bigelow said.

NASA is studying using expandable habitats for a crew’s living area on far-flung missions into deep space, such as an asteroid or Mars. The BEAM module is a stepping stone to demonstrate the new technology in the actual space environment before moving to the larger designs of B330.

“It is the future,” said Kirk Shireman, NASA’s manager of the International Space Station program. “Humans will be using these kinds of modules as we move farther and farther off the planet and as we inhabit low-Earth orbit. So I think it really is the next logical step in humans getting off the planet.”

Our Atlas archive.