STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

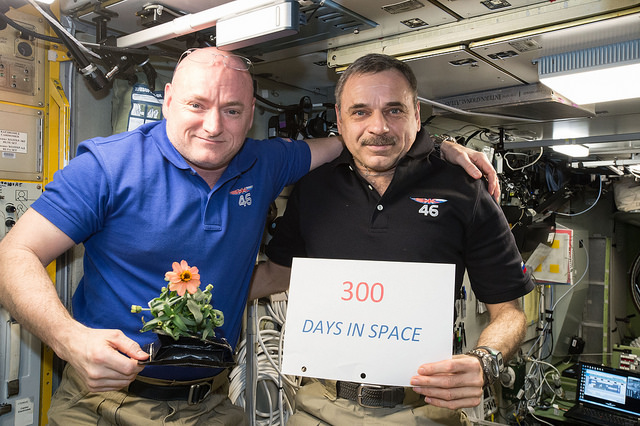

Astronaut Scott Kelly and cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko are making final preparations for return to Earth Tuesday evening, closing out a record 340-day stay aboard the International Space Station where they served as medical test subjects to learn more about the long-term effects of weightlessness, space radiation and isolation.

While looking forward to reunions with family and friends after nearly a full year in space — the longest flight ever by an American — Kelly says he still has enough gas in the tank for several more months in space if not another year, more than enough for a long-duration flight to Mars.

“Yeah, I could go another hundred days, I could go another year if I had to,” he told reporters last week. “It would just depend on what I was doing and if it made sense, although I do look forward to getting home.”

The rationale behind the nearly year-long mission was to collect the most extensive data yet on the physical and psychological impacts of long-duration spaceflight, including a genetic comparison of Kelly and his twin brother Mark, a former shuttle commander who participated in many of the same experiments on Earth.

“From a subjective perspective, I think absolutely, I feel great,” Scott Kelly said. “But there are the things you can’t see, like bone loss and the effects of radiation on you at a genetic level, and that’s something we might not know about for years to come, how long term that amount of radiation has affected me.

“But subjectively, I feel great, and I think it’s something that, going to Mars and having people stay in space for much longer than we have before, is clearly doable.”

While he said he wouldn’t mind a filet mignon once back on Earth, what he really missed — and what he is looking forward to the most — is simply the experience of human companionship beyond the restricted confines of the space station.

“It’s interesting, I look forward to fresh food, like a salad, believe it or not, stuff like that,” he told a NASA interviewer in January. “But specific things are not as important as the experience.

“I actually look forward to sitting at a table and just relaxing and having a meal with friends and family when you don’t have to worry about your spoon or your fork or your food floating away and dealing with the overhead of that. … The other things I’m looking forward to is seeing the sky from below, and air that is fresh, a breeze and the sun on my face, running water. People.”

Kelly, Kornienko and Soyuz TMA-18M commander Sergey Volkov, who is wrapping up his own 182-day stay in orbit, plan to undock from the station’s upper Poisk module at 8:02 p.m. EST (GMT-5) Tuesday, pulling away to a distance of about 12 miles.

Then, at 10:32 p.m., Volkov, flanked on the left by Kornienko and on the right by Kelly, will oversee an automated four-minute 49-second firing of the Soyuz spacecraft’s braking rockets, slowing the ship by 286 mph to drop the far side of its orbit deep into Earth’s atmosphere for a descent to Kazakhstan.

After a 25-minute free fall, the Soyuz descent module will slam into the discernible atmosphere at an altitude of about 62 miles, enduring about five minutes of extreme heating while descending to an altitude of about 20 miles.

If all goes well, the descent module’s large parachute will deploy at an altitude of about 6.6 miles and the spacecraft will settle to a jarring rocket-assisted touchdown on the steppe of Kazakhstan, some 87 miles from Karaganda, at 11:25 p.m. (10:25 a.m. local time).

A veteran of two space shuttle flights and a 159-day stay aboard the space station in 2010-11, Kelly has one previous Soyuz launch and landing to his credit, an experience that he said defies easy description.

“The Soyuz is a pretty exciting ride back Earth, no question about it,” he said. “People who have flown in it previously will try to prepare you for it, but I think nothing really can until you’ve actually be there yourself and experienced it. it’s definitely an eye opener!

“Once you get past the initial shock of the drogue chute opening and all the pyrotechnics firing for various reasons, certainly coming through the atmosphere, the plasma that’s right next to your head … definitely gets your attention. It’s so much fun for me that I said after my last flight, if I’d hated being in space for six months I’d have done it all over again just for that last 20 minutes in the Soyuz. It’s that type of an experience.”

Russian recovery forces stationed near the landing site will help the returning space fliers out of the descent module, carrying them to nearby recliners for initial medical checks and satellite phone calls home to friends and family.

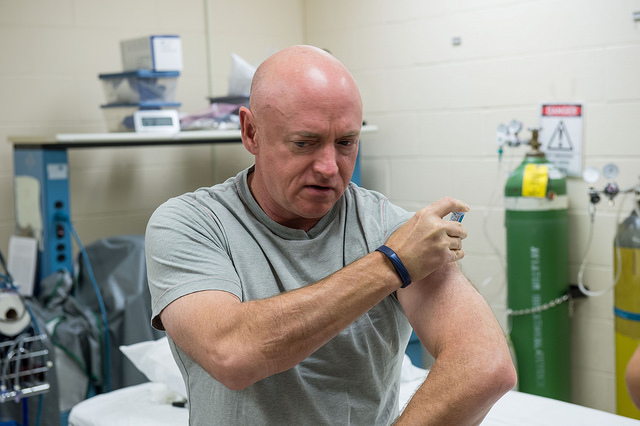

All returning station crew face a battery of tests to determine their condition and to help with their re-adaptation to gravity. But Kelly and Kornienko will face more extensive checks than usual because of the long duration of their flight and the numerous experiments they are subject to.

“Right after we get out of the Soyuz, they’ll put us in the chairs that people often see sitting nearby the spacecraft,” Kelly said. “From there, we go into this medical tent and once we’re inside the medical tent, we’ll be given a little bit of time to adjust but then we go through about an hour of field tests, that is, various types of experiments.”

Some tests will be as simple as having Kelly and Kornienko stand up and sit down, and moving about the tent on their own “to look at our physiology (as we) adjust to those different positions.” And then there are the blood draws, scans and detailed laboratory analysis to precisely measure how their bodies re-adapt to gravity.

“No such thing as time off from the medical guys,” NASA Administrator Charles Bolden told CBS Radio. “Because he is a walking, breathing, living medical specimen, time is of the essence. When they pull him out of the capsule and they get him on the airplane headed back to Houston, medical tests begin immediately.

“What the docs want to see, as quickly as they can, they want to get as much data as possible because with every minute the body begins to re-acclimate to being in a gravity environment. So they want to make sure they capture as much data as they can from him in the early stages of his re-adaptation. He will have about a 45-day rehabilitation period.”

Kelly, Kornienko and Volkov will be flown by helicopter to Karaganda. From there, Volkov and Kornienko will head back to Star City near Moscow for additional tests and debriefing while Kelly will fly back to the Johnson Space Center in Houston aboard a NASA jet, arriving late in the evening on March 2.

After additional medical checks, Kelly said his top priority is going home and taking a shower or jumping in his pool — a chilly prospect given Houston’s recent weather.

“Leaving this amazing facility is going to be tough, because I probably will never see it again,” he said. “I don’t expect I will, I’ve flown in space four times now so it’s going to be hard in that respect. But I certainly look forward to going back to Earth. I’ve been up here for a really long time and sometimes, when I think about it, I feel like I’ve lived my whole life up here.”

Kelly and Kornienko joined cosmonaut Gennady Padalka for the flight to the space station last March. Padalka then returned to Earth the following September, in the process becoming the world’s most experienced spaceman with 878 days in orbit over five flights.

The TMA-16M spacecraft was replaced by TMA-18, delivered by Volkov, who at landing will have logged 548 days in space over three flights.

During the course of their stay in space, Kelly and Kornienko covered more than 143,840,000 miles over the course of 5,440 orbits, witnessing some 10,900 sunrises and sunsets. They helped or participated in six spacewalks — Kelly carried out three EVAs while Kornienko participated in one — they welcomed six unpiloted supply ships and three Soyuz crew ferry craft.

Kelly and his U.S. and European crewmates participated in some 400 on-board experiments in a wide range of disciplines, including fluid physics, materials science, biology, animal research and the medical studies to learn more about the effects of spaceflight on human physiology and psychology.

And, according to The New York Times, Kelly will have consumed 193 gallons of recycled urine and sweat, jogged 648 miles on station treadmills and posted some 713 photos on Instagram.

“I have taken a lot of pictures because I’ve been up here for a long time,” Kelly said. “Actually, numbers wise, I don’t think I’ve taken that much compared to other crew members we’ve had up here. But I’ve definitely taken some good ones and some memorable ones.”

And he also found time to generate a few laughs. He recently donned a gorilla suit, chasing British astronaut Timothy Peake through the station in a short, widely-viewed video posted on Twitter. The idea came from his twin brother, Mark.

“When you try to get kids’ attention and teach them about science and math and engineering and things like that, the first thing you have to do is get their attention,” Kelly said. “And nothing gets people’s attention like a gorilla in space. So I think I’m going to use that video for a long time to come with kids.”

But the science of long-duration spaceflight was the name of the game.

Four Russians spent more than a full year in space aboard the Mir space station. Vladimir Titov and Musa Manarov each logged 366 days aloft while Sergei Avdeyev spent 380 days in orbit and Valery Polyakov logged 438 days.

But they were not subjected to the same level of peer-reviewed international research with state-of-the-art medical technology as Kelly and Kornienko. Julie Robinson, director of space station science for NASA, said Kelly’s flight was essentially “a pilot study.”

“So we are building from ISS a significant body of understanding, on both what the effects are on the human body and also how to prevent those effects,” she said. “You don’t start with the full investigation. You do a pilot study, you get a little experience, then you evaluate from that initial data whether you need to have a big program or whether you’re really good to go with the other research that you’re doing.”

Kelly and Kornienko represent just two data points and more research will be needed before astronauts head out to Mars. One major unknown is the effects of space radiation beyond the protection of the Van Allen belts that shield Earth from the effects of solar storms.

Another major question mark is the effects of weightlessness on vision. Many astronauts suffer changes in weightlessness that affect the shape of their eyeballs and the acuity of their vision. Some make near or complete recoveries once back on Earth, both others do not.

And then there is the twins research.

Starting well before launch, the Kelly twins were subjected to the same tests, blood draws, medical scans and the collection of urine and saliva samples. Both continued data collection after Scott’s launch and both will continue to provide samples well after the mission is over, helping researchers pinpoint changes that were the result of gravity, or its absence, space radiation and other factors.

“That study is looking at a lot of important things between my brother and I, our physiology and how it changes over time,” Scott said last week. “One part of it is kind of a new area that NASA is getting into with this study, the effects of spaceflight on a genetic level.

“That’s something I’m pretty excited about for personal reasons but also for the research to try to have a better understanding of how this microgravity environment and the radiation environment affects us genetically. There’s a lot to learn … so it’s great to see us starting to focus on that in space as well.”

Along with figuring out how to mitigate the most harmful aspects of long-duration spaceflight, the designers of the spacecraft that eventually carry astronauts to the red planet will need to incorporate lessons learned from the space station to ease the psychological stress of such a voyage.

A Mars-bound spacecraft will not be nearly as roomy as the International Space Station, Kelly said, and “obviously, you’re going to be in much tighter quarters, you’re going to live, you’re going to use the rest room, you’re going to exercise all within a few square meters of one another I assume.”

“It’s not going to be like the science fiction spaceship going to Mars, it’s going to be something much smaller,” he said. “And even though our crew quarters and our privacy is pretty good in what we have here, I think it’s going to have to be a lot better. … Making that private area as perfect as possible, I think, will go a long way toward reducing fatigue, reducing stress and helping for a successful mission.”

Bolden said no decisions will be made about additional long-duration flights aboard the space station until researchers complete their current studies. Among the options are another year-long mission or perhaps an even longer stay aboard the station.

But maybe not.

“One of the things that seems to be popping up more frequently is the concept of a sample where you take a crew member, or a set of crew members, fly them on a nominal station mission of six months, bring them back to Earth, let them do some normal duties for a month or two or three or maybe six, and then turn them right around for another six-month increment (aboard station).”

That would simulate an actual flight to Mars in many respects, Bolden said, to demonstrate “what it would be like for someone to transit to Mars, work on the surface in a gravity environment for a while and then get back in a spacecraft and come back.”

“No decisions have been made on just what the next course of action might be,” Bolden said. “My guess is they’ll take a look at Scott and Mikhail’s data, they’ll look at some of the other long-term data from mostly Russian flights and then make a decision on what the next phase of the test is.”

And what of Kelly’s plans? He hasn’t said, but told reporters last week he plans to stay involved in space flight in some capacity.

“I will always try to stay involved in the space program in any capacity that will be allowed,” he said. “There are times when you transition from one thing to another, but this has been my life, and it’s something I feel very strongly about and want to be a big part of for the rest of my life.”