Soaring into the night sky over a guarded Russian military base, a 1.2-ton European satellite rocketed into orbit Tuesday to regularly measure how the world’s oceans and ice sheets respond to climate change and drive global weather patterns.

Valued at more than $400 million, the Sentinel 3A mission is set to last at least seven years, tracking changes in the planet’s sea level, ocean color, marine organisms like algae and phytoplankton, ice sheets, and rivers and lakes.

The spacecraft took off aboard a 95-foot-tall (29-meter) Rockot launcher at 1757:40 GMT (12:57:40 p.m. EST) from Complex 133 at the Plesetsk Cosmodrome in far northern Russia, streaking through clouds as it pitched north and climbed into space over the Barents Sea.

The Rockot is a modified launcher based on the SS-19 ballistic missile, a Soviet-era booster from the Russian military’s nuclear forces. Engineers added a Breeze KM third stage to the two-stage SS-19 missile to outfit it for satellite launches.

The launcher shed its SS-19 missile parts — the first and second stage, plus a nose cone enclosing Sentinel 3A — in the first five minutes of the flight to fall into the Arctic Ocean. The Breeze KM engine next ignited for the first of two maneuvers to steer the 2,526-pound (1,146-kilogram) spacecraft into orbit.

The first firing placed Sentinel 3A in a preliminary egg-shaped orbit, and the Breeze KM engine ignited again an hour later to circularize the satellite’s orbit at an altitude of more than 500 miles (about 800 kilometers).

The upper stage was programmed to release Sentinel 3A in space at 1917 GMT (2:17 p.m. EST) while it was out of range of ground stations.

A few minutes later, ground controllers at the European Space Agency’s satellite operations center in Darmstadt, Germany, heard signals from Sentinel 3A and verified its health after the fiery trip into space, prompting a round of applause in the control room.

Officials later confirmed the satellite — about the size of a minivan — extended its power-generating solar panel after internal torquers stabilized the spacecraft following deployment from the launch vehicle.”

“The spacecraft status is nominal, so it couldn’t have been better so far,” said Andrea Accomazzo, a flight director at the European Space Operations Center.

ESA and Eurockot, the Russian-German company in charge of commercial Rockot missions, declared Tuesday’s launch a total success.

By Friday night, engineers plan to activate all of the satellite’s major systems and declare Sentinel 3A ready for tests of its four Earth observation instruments, a sensor suite that makes it arguably the most complex in Europe’s line of Copernicus environment satellites, according to ESA.

“This is the third of the Sentinel satellites launched in the less than two years – and it is certainly a special moment. It also marks a new era for the Copernicus Services, with Sentinel 3 providing a whole range of new data with unprecedented coverage of the oceans,” said Volker Liebig, director of ESA’s Earth observation programs.

Managed by the European Commission — the executive body of the EU — the Copernicus program is Europe’s most expensive space project. It will be the world’s largest Earth observing system when complete in the early 2020s, and Europe will have spent nearly $10 billion on the program by the end of the decade.

Unlike Europe’s previous Earth observation satellites, politicians and scientists crafted the Copernicus program with an eye toward tangible applications, such as security, environmental stewardship, commercial users and climate monitoring.

The difference lies in the types of data collected by the Sentinel satellites compared to earlier science missions, and the rapid delivery of measurements to forecasters, security agencies and other users within hours of their capture.

ESA manages the development of the Sentinel satellites and their launches for the Copernicus program on behalf of the European Commission.

European officials plan to launch a series of satellites of each type to ensure continuous measurements. The second member of the Sentinel 3 line, Sentinel 3B, is due for liftoff by the end of 2017 to double the rate at which the Sentinel 3 system can map the world’s oceans, eventually reaching a cadence of every two days.

“Each Sentinel has a specific duty,” said Guido Levrini, ESA’s Copernicus space segment program manager. “Sentinel 1 is more specifically tailored to emergency response. Sentinel 2 is focused on monitoring the land. Sentinel 3, together with Sentinel 6, is focused on moinitoring the ocean and waters. Sentinel 4, together with Sentinel 5, is specially tailored toward monitoring of the atmosphere.”

Built by Thales Alenia Space, Sentinel 3A will be operational in July, beginning a mission expected to last at seven years, said Bruno Berruti, ESA’s Sentinel 3 project manger.

The satellite has enough fuel to last through 2028.

Sentinel 3A’s instruments will measure global sea levels, detect the temperature of sea water, and determine the color of land and ocean surfaces worldwide.

“A powerful radar altimeter, together with a microwave radiometer, will be able to measure the height of the sea surface to an accuracy of 2 centimeters (0.8 inches) from 815 kilometers (506 miles) up in space,” said Craig Donlon, Sentinel 3 mission scientist at ESA. “We also have a thermal infrared radiometer, which will measure the temperature of the Earth, and that can measure the temperature of the ocean surface to an accuracy of about 0.2 degrees Celsius. You try measuring the temperature of your bath water to that accuracy.”

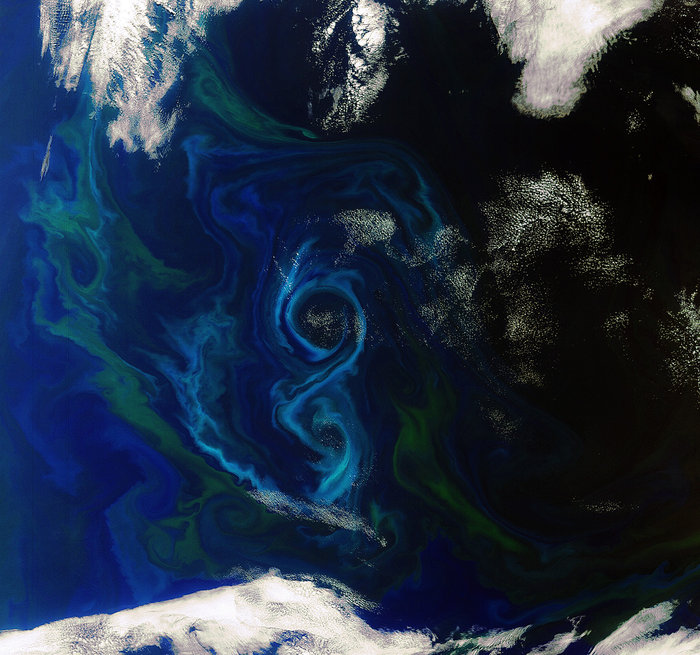

An multi-spectral camera seeing in 21 visible and near-infrared bands will capture the colors of the sea, revealing oil spills, algae blooms, and plankton spreading across the ocean.

“Marine forecasters will be able to use the Sentinel 3 data in the same way as our weather forecasters have been suing weather satellite data,” said Francois Montagner, marine applications manager at Eumetsat, Europe’s weather satellite agency and a partner in the Sentinel 3A mission.

“Combining the sea level information and the sea surface temperature information actually allows us to estimate the total amount of heat in the ocean from the surface, which is seen directly, down to the very bottom,” Montagner said. “The ocean color imager will see plankton and water quality, not just at the surface, but also in the first few tens of meters, where most of the life happens.”

Sentinel 3A will work with the U.S.-European Jason 3 oceanography satellite launched from California in January to monitor the heights of waves and sea level. The two satellites together, along with the SARAL mission jointly managed by France and India, allow more regular wave measurements, officials said.

Four more Sentinel satellites are due for liftoff in the next 20 months, according to Liebig.

The next launch for the Copernicus program is tentatively set for April 12, when a Soyuz rocket will carry up Sentinel 1B from French Guiana, the second in a set of radar-equipped satellites tailored to help authorities respond to natural disasters and other emergencies.

“We are now creating a system which will last forever,” Liebig said Tuesday. “We have already contracted, and the budget is available, so we are already sure that we can maintain everything far into the 2030s, depending a little bit on each satellite’s lifetime, which gives the users insurance that they can build their applications on it, and this is a major step forward.”

Europe supplies Sentinel satellite data to the global community free of charge.

“One of the contributions we wanted to have is our own eyes in space,” Liebig said. “We were, for 35 years, very dependent on Landsat, for example, a fantastic system, (but) now it is a bit outdated because Copernicus delivers much better data.

“This is one of the reasons the U.S. has started to use our data, so now we have our own eyes in space, but we offer this (data) to everybody. The data are free. All nations of the planet can use the data to assess the environment in their countries.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.