CAPE CANAVERAL — On top of an Atlas rocket, the place where orbital spaceflight for American astronauts began, will sit Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft to launch humans into space starting next year.

It was Feb. 20, 1962 when an Atlas D booster blasted off with Project Mercury’s Friendship 7 capsule and John Glenn to become the nation’s first person to orbit the Earth.

More than a half-century later, a bold new era of commercial travel to and from space is about to start, and Atlas rockets will again play a pivotal role.

The domestic access to space for U.S. astronauts has been stymied since the winged shuttle orbiters were retired from service in 2011, leaving NASA to purchase seats aboard Russian Soyuz crew capsules flying up and down from the International Space Station.

The Soyuz, a reliable ship for sure, launches and lands in Kazakhstan, away from the limelight and national pride of Americans who once flocked to Florida’s Space Coast for a glimpse of man departing the Earth atop a rocket’s brilliant glare.

But next year, after enduring budget-related delays, NASA’s Commercial Crew Program is poised to launch its first astronauts from U.S. soil.

“I remember when I launched from Kennedy the first time on a U.S. space shuttle and it was pretty amazing. So I can only imagine what it’s going to be like after this long period of time to get back on a spacecraft at Kennedy and have family and friends and people from all over the country watching. That’s going to be pretty special,” said Suni Williams, one of the astronauts now training to fly on a Commercial Crew spacecraft.

“I think we have lost a little bit of that in the last couple of years because we were launching from so far away in Kazakhstan with the Russian space program. So bringing that back home to everybody here, it will be a pretty exciting moment.”

NASA has assigned a four-person cadre of astronauts that will fly the initial test flights of the Starliner and Dragon spacecraft. They put a human face on the vehicles and are integral to building the partnerships between NASA and the commercial providers.

All are veteran space shuttle astronauts and military test pilots:

* Air Force Col. Bob Behnken, a two-time space shuttle mission specialist and former chief astronaut. After graduating Air Force Test Pilot School, he was a flight test engineer for the F-22.

* Ret. Air Force Col. Eric Boe, a two-time shuttle pilot including Discovery’s final mission. He graduated Air Force Test Pilot School and was assigned as the director of test for Air-to-Air Missile Test Division flying the F-15 and UH-1N.

* Ret. Marine Col. Doug Hurley, a two-time shuttle pilot including the final flight in 2011. He graduated from Naval Test Pilot School and was assigned to the Naval Strike Aircraft Test Squadron, becoming the first Marine pilot to fly the F/A-18 E/F Super Hornet.

* Navy Capt. Suni Williams, a veteran of 322 days in space, launching aboard Discovery on her way to serving as a flight engineer aboard the space station’s Expedition 14-15 crew, then later flying aboard a Soyuz to be commander of Expedition 33. After graduation from the Naval Test Pilot School, she was assigned to the Rotary Wing Aircraft Test Directorate as an H-46 project officer and later returned to the school as an instructor.

“It’s really been the dream of all of us to participate in the test of a new vehicle, and a vehicle like a spacecraft is the gem of a career for folks,” Behnken said.

“I would have been embarrassed as a Test Pilot School graduate to not jump at the opportunity, if it was offered to me, to fly a new spacecraft.”

Engineers and technicians, diligently working today in factories across the country, are building new spacecraft and the rockets to launch them, a commercial endeavor by The Boeing Co., United Launch Alliance and Space Exploration Technologies Corp. for NASA and the nation.

The firms will share the role of taxi service for crew members going to low-Earth orbit, with Boeing’s Starliner craft being launched atop United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rockets and the SpaceX capsules flying on the company’s Falcon 9 booster.

“We are excited to be back in manned flight again. There’s a lot of experience that we bring to the table regarding manned flight and we are thrilled to pieces to have our partners to work with to get some smoke and fire back on the launch pad,” said Steve Payne, who orchestrated space shuttle countdowns and now serves in the Commercial Crew Program at Kennedy Space Center.

“But it is their show. This is the beginning of a whole new industry of commercial spaceflight. Someday you’ll be able to go buy a ticket and fly as well.”

Manufacturing of the Starliners is underway at Kennedy Space Center’s former shuttle hangar now occupied by Boeing. ULA begins building the first man-rated Atlas 5 rockets this spring at its sprawling plant in Decatur, Alabama.

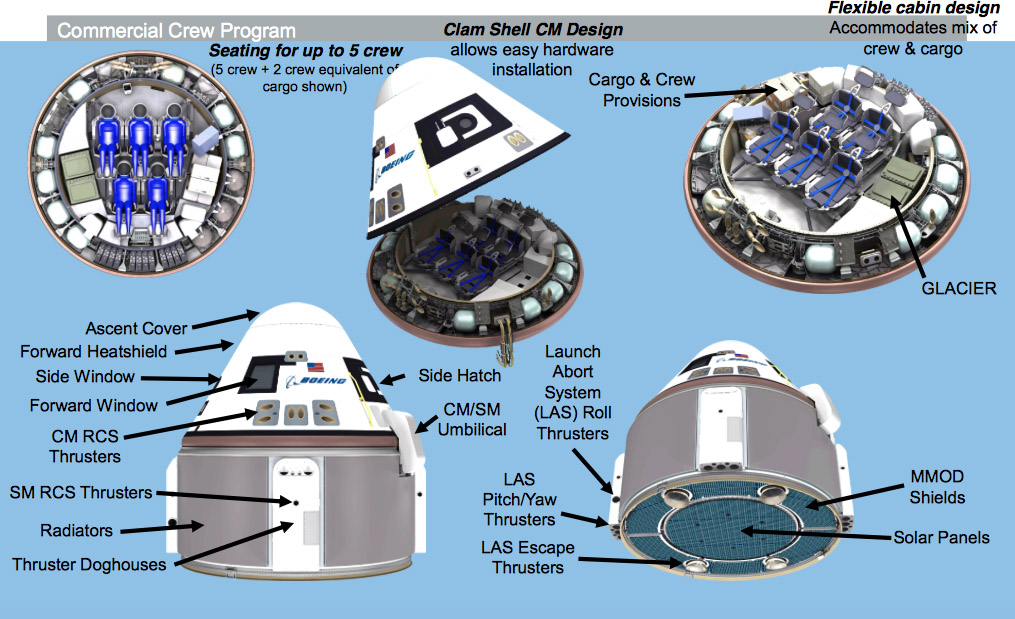

Starliner, originally dubbed the Crew Space Transportation (CST) -100 spacecraft, can accommodate up to seven passengers or a mix of crew and cargo to low-Earth orbit. It features an automated docking system and a parachute and air bag system for soft land landings.

Boeing’s Orbital Flight Test, or OFT, is targeted for next summer aboard Atlas 5 tail number AV-076. It will be an unmanned checkout mission for the Starliner spacecraft, flying up the International Space Station and docking for a brief stay before returning to Earth for landing.

Then comes the Crewed Flight Test, or CFT, next October, if all goes well, to take a Boeing test pilot and a NASA astronaut to the space station for a full-up demonstration of the commercial ferry service. It will launch atop Atlas AV-079.

“Shuttle was a very complicated system and it had some drawbacks because of the tiles, the fragility, and the foam on the tank. These are simpler systems with fewer moving parts,” Payne said.

“The capsules are newer with all of the design issues that we discovered in the past that we didn’t want to do again worked out. So we have a lot of clever, new design ideas incorporated.

“As far as the launch vehicle goes, the Atlas 5 is a tried and tested vehicle that has been doing this for many years and has many successful launches behind it.”

Once the system is completely checked out, NASA will send its first full crew to the station aboard either Starliner or Dragon, likely in early 2018.

The Atlas 5 rocket has flown 60 times, all successfully, since 2002, launching a variety of satellites for the U.S. military, intelligence community, NASA and commercial operators.

“It’s really starting to get very exciting,” said Gary Wentz, United Launch Alliance’s vice president of Human Launch Services.

“It’s really transforming the ULA business towards NASA and space station as a prominent part.”

Heaving the hefty Starliners into low-Earth orbit will require the Centaur upper stage be outfitted with two Aerojet Rocketdyne RL10 engines instead of one. Dual-engine Centaurs have flown for decades, but never on an Atlas 5 rocket.

“It really opens up our capability to carry this larger payload,” Wentz said.

Boeing has not publicly released the exact mass of Starliner.

There’s also the rigorous process to ensure the launch vehicle is safe for its human riders.

“It is really about testing and certifying the systems to a different set of reliability and margin requirements that are appropriate when we are actually going to put human beings there. So far, so good,” Tory Bruno, ULA’s president and CEO, said on The Space Show program earlier this month.

“We work closely, very hand in glove, with NASA to make sure that these unique requirements for human certification are met and all of their experts are coming along step by step with my people to make sure there is complete transparency and that we are all confident that it is safe to put people on top of that giant rocket when the time comes. We have a plan that we’ve agreed upon and we are marching through that with NASA.”

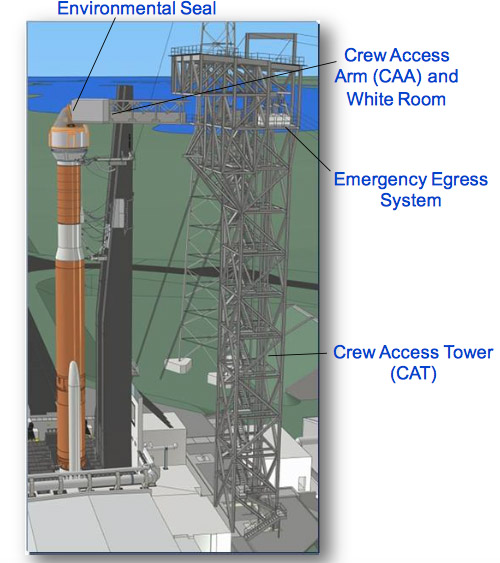

Construction of a crew access tower is nearing completion at the Atlas 5 rocket’s Cape launch pad. The new gantry, positioned in the northwest corner of the pad, was built in sections off-site and moved to Complex 41 in between ongoing Atlas launch activities for stacking.

“It was a great challenge and I’m very proud of how both the ULA and construction teams worked together in unison to work around our busy launch manifest last year,” said Wentz.

“It was a very well choreographed activity and the team at the Cape did an exceptional job putting that together.”

The tower stands 200 feet tall and features an elevator to take personnel from the ground to the top and a 42-foot-long swing arm that will be the threshold to enter the capsules.

The arm, which is undergoing testing of its retraction mechanism off-site, will be installed on the pad this summer.

“The team is out there right now working on the tower, focusing on the mechanical, electrical, plumbing connections, outfitting the elevator and putting on some final skins to protect the tower,” Wentz said.

Also still to come will be implementing an emergency evacuation system for pad personnel and the flight crews.

“We have looked at several different systems. We are in the final phase right now of selecting that emergency egress system and hope to select that within the next month or so,” Wentz said.

The whole tower system should be operational by this fall.

“I’m going to be really excited when we get to put people on spacecraft at Kennedy Space Center. It is going to be pretty amazing for our whole country, for the whole world, when you think of the implications of this advanced technology in a spacecraft,” Williams said.

The first chance to get astronauts inside a Starliner at the launch pad, likely, will be several weeks before the first flight to simulate crew activities and for the launch team to exercise the day-of-launch communications plan. ULA also intends to conduct a wet dress rehearsal to go through a realistic countdown before that initial mission, Wentz said.

The Atlas rocket stages will be stacked aboard a mobile launch platform, the solids affixed to the vehicle and Starliner hoisted atop the Centaur at the Vertical Integration Facility. The fully assembled launcher will be transported on rail tracks some 1,800 feet to the pad the day before liftoff, keeping with standard Atlas 5 practices, for follow on Starliner missions.

Today’s Atlas launch countdown lasts for about seven hours to power up the rocket, run through the testing protocols and then load cryogenic liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen into the vehicle during the last two hours. A hold occurs at T-minus 4 minutes, usually lasting 15 minutes, to perform the final readiness polls and grant approval for entering the last phase of the count.

But the manned Atlas countdowns will see the timeline expanded by four hours to a total duration of 11 hours. Activities will follow today’s script to T-minus 4 minutes, with the cryogenic tanks entering stable replenish mode, before diverging to the new era.

That’s when a four-hour hold will occur as the astronauts depart the crew quarters and travel to the launch pad, board the capsule and run through communications checks with mission control.

A closeout team of less than 10 people representing Boeing, NASA and ULA will assist the crew into the spacecraft and get strapped in, Wentz said.

The Atlas 5 rocket’s first experience taking aim at the International Space Station last month with a commercial Orbital ATK Cygnus cargo freighter had a 30-minute launch window. But that won’t be the case with Starliner launches.

“It will be an instantaneous launch window because of the mass of the vehicle and the trajectory,” Wentz said.

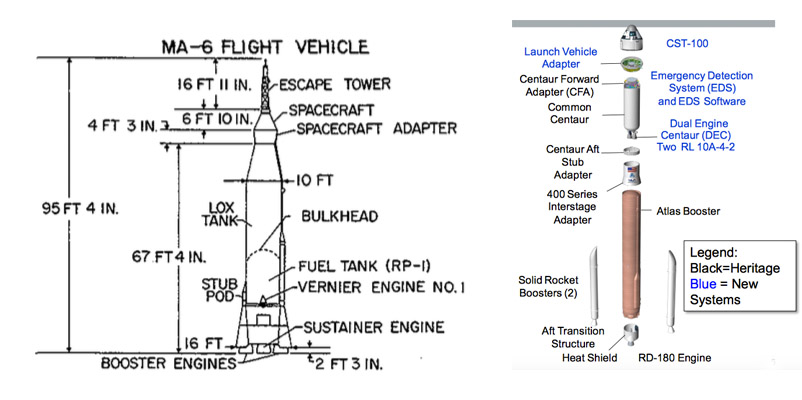

It took five minutes of propulsion by the one-and-a-half-stage Atlas D rocket, with a liftoff thrust of 360,000 pounds from the booster engine package and sustainer engine, to put John Glenn’s 3,000-pound, single-occupant capsule into orbit for a five-hour, three-revolution trek for the free world.

The modern Atlas 5 will unleash 1.5 million pounds of thrust from its kerosene-fueled RD-180 main engine and two strap-on solid rocket boosters to begin the journey to space with Starliner.

The Centaur upper stage, fueled with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, then performs a 7.5-minute burn to propel the capsule, deploying it roughly 15 minutes and 42 seconds after liftoff.

It’s officially known as the 422 variant of the Atlas 5 rocket, standing 172 feet tall. In comparison, John Glenn’s launcher was a mere 95 feet tall.

Throughout the ascent, the Starliner spacecraft will have the ability to declare an abort and separate from a malfunctioning rocket, through its liquid-propelled pusher abort system, to immediately return to Earth and save the crew.

“We have a chance to build upon a new launch capability for America,” said Hurley.

“It’s kind of like climbing a mountain, going up hill is only half the trip. So we have to make sure we get everyone back safely as well, and then build a reliable vehicle that can continue to take our crews to the space station.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SFN’s lead ULA writer

Justin Ray has been a reporter with Spaceflight Now since the website’s inception in November 1999. The online news service, based at Cape Canaveral, has documented U.S. and international space news with a specialty of live launch coverage.

Prior to that, Justin worked for two years as an aerospace reporter at the Florida Today newspaper and its pioneering Space Online website. He began his career as an intern at Patrick Air Force Base’s public affairs office in 1996 and wrote for the Missileer base newspaper.

The Ohio native has covered 139 Delta rocket launches, 108 Atlas flights, 65 space shuttle missions and construction of the International Space Station, plus scientific spacecraft such as the Mars rovers and Cassini.

He attended college at the University of Central Florida and now resides in Satellite Beach, Florida.