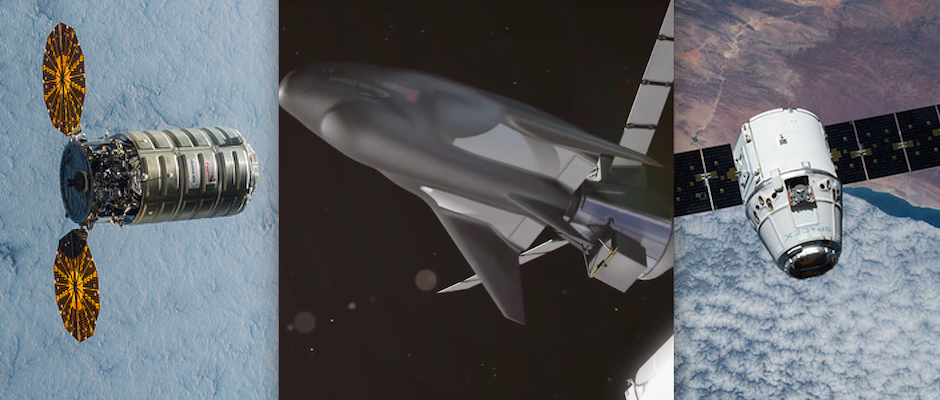

An unpiloted space plane developed by Sierra Nevada Corp. will join cargo carriers built by SpaceX and Orbital ATK to resupply the International Space Station beginning in 2019, NASA announced Thursday.

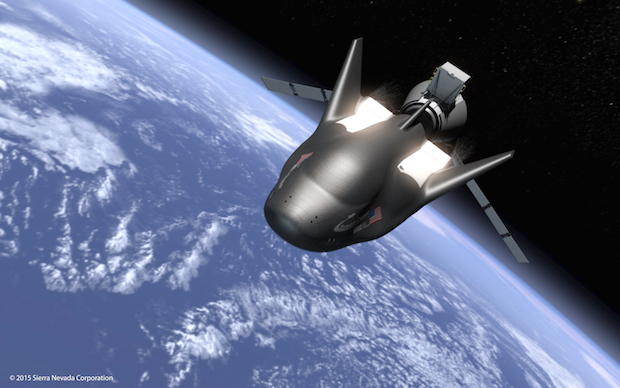

The Dream Chaser spaceship, originally conceived to carry astronauts, can deliver up to 12,000 pounds — 5,500 kilograms — to the space station per trip, then detach and return to Earth for a runway landing like the space shuttle.

Sierra Nevada’s lifting body spacecraft has never flown in orbit, and the company aims to drop the craft from a helicopter for an approach and landing demonstration in the coming months.

NASA’s current cargo transportation providers, SpaceX and Orbital ATK, also received new contracts Thursday, giving the space station three U.S. resupply carriers operating alongside Russia’s Progress logistics freighter and Japan’s HTV cargo ship.

The cargo flights covered by the new agreements will begin in 2019, and the contracts have options for missions extending through 2024, the space station’s current projected retirement date.

NASA signed the agency’s previous commercial cargo contracts with SpaceX and Orbital ATK in December 2008, and those Commercial Resupply Services — or CRS-1 — agreements have been extended to meet the space station’s supply needs through 2018.

The space agency turned to commercial providers to haul supplies to the space station after the retirement of the space shuttle, and NASA plans to debut new commercially-owned crew capsules developed Boeing and SpaceX to transport astronauts to and from the orbiting research lab in 2017.

NASA officials said Thursday they chose three companies to expand their options when routing experiments, crew provisions and other hardware between Earth and the space station.

“One of the considerations from an operational standpoint with ISS is it’s really important to have more than one supply chain, and mulitple offerers means that at any given time, the sequence of flights could be one Sierra Nevada, Space, Orbital ATK, so if you lose one, you have the ability for another one being right after it from a dissimilar redundancy, or a different supplier, so that’s a big help to us,” said Kirk Shireman, NASA’s International Space Station program manager at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

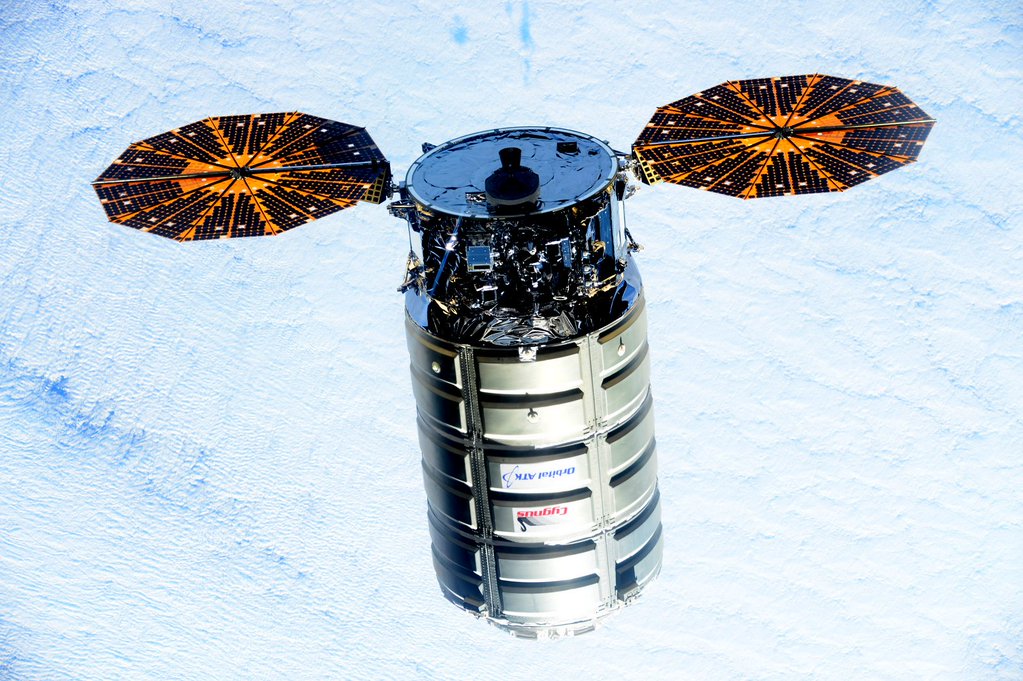

Orbital ATK and SpaceX had launch failures in October 2014 and June 2015, grounding their Cygnus and Dragon supply ships for months. Orbital ATK purchased two United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket flights to keep flying the Cygnus spacecraft while the company’s Antares booster is grounded.

SpaceX has resumed flying its Falcon 9 rocket after its launch mishap, and the next Dragon cargo mission to the space station is scheduled for no sooner than March, nine months after last year’s failure.

Sam Scimemi, director of the space station’s division office at NASA Headquarters, said the agency learned lessons from the first round of cargo contracts cinched in 2008.

“It has not been easy by any measure,” Scimemi said. “Both our CRS-1 providers have experienced launch failures and are in the process of recovering. NASA and our industry partners have learned valuable lessons from these failures and the recovery to flight.”

SpaceX and Orbital ATK have carried a combined 35,000 pounds of gear to the space station since commercial flights to the outpost began in 2012, Scimemi said.

The fresh cargo contracts, which go into effect immediately, have an aggregate value of up to $14 billion. Tenets of the deals allow NASA to order additional missions beyond each company’s six guaranteed flights as needed until the total cost reaches $14 billion, and Shireman said the space station’s actual cargo requirements will almost certainly fall short of the cap.

NASA can procure the add-on cargo flights based on price, capability, past performance and other factors.

“The contract has a minimum of six missions per selectee, so in that sense, everyone is going to get the minimum,” Shireman said. “It is likely we will buy more than 18 flights, so we have three winners, and if we need more than 18 flights, then we’ll talk about what happens on those flights.”

NASA did not disclose the value of each contractor’s base award for six cargo missions, but Orbital ATK said in a press release its six initial flights are valued at $1.2-$1.5 billion. Sierra Nevada and SpaceX did not provide financial figures for their agreements.

In a change from the previous cargo contracts, NASA requested bidders to offer different types of mission scenarios to give space station managers flexibility in ordering a cargo flight to match the needs of the moment.

Orbital ATK’s Cygnus spacecraft currently primarily launches aboard the company’s internally-developed Antares rocket from Wallops Island, Virginia. Company leaders billed the switch to ULA’s Atlas 5 as a temporary fix while the Antares booster prepares to resume launches later this year.

According to Shireman, Orbital ATK submitted a proposal offering three types of mission — two with delivery and disposal of pressurized cargo like food, spare parts and small experiments, and one to take up and get rid of large units and instruments mounted outside the space station. NASA can also decide whether they want to launch the missions aboard Orbital ATK’s Antares rocket from Virginia or ULA’s Atlas 5 from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

“By utilizing the flexibility of our Cygnus spacecraft, combined with a mixed fleet of launch vehicles, Orbital ATK is providing NASA a complete portfolio of mission options to fulfill their cargo delivery needs,” said Frank Culbertson, president of Orbital ATK’s space systems group.

Sierra Nevada outlined two mission scenarios, both with the ability to haul internal and external cargo to the space station, dispose of trash, and return supplies to the Earth intact inside the Dream Chaser’s pressurized compartment.

NASA has the option for the Dream Chaser to directly dock to the space station or be captured with the lab’s robotic arm. Each technique has benefits, with dockings permitting the space plane to reboost the space station’s orbit, while the capture and berth method allows astronauts to transfer equipment through a larger hatch on the outpost’s Harmony or Unity modules.

The Dream Chaser will launch on ULA’s Atlas 5 rocket, employing the launcher’s 500-series configuration with a 5.4-meter (17.7-foot) fairing.

Shireman said SpaceX’s bid included options, too.

Like the Dream Chaser, SpaceX’s Dragon cargo ship could dock or be grasped by the space station’s robotic arm, he said. SpaceX also proposed landings of the Dragon cargo capsule in the ocean or on land.

“We’re going to decide which type of mission do we need at any given time,” Shireman told reporters Thursday. “Price will be a factor, but it’s only one of many, many factors. It’s not like going and buying gas from a gas station, where you just find the cheapest one and go buy it. It’s much more complicated than that.”

Shireman said the new crop of upgraded cargo carriers will deliver heavier loads to the space station than existing U.S. commercial vehicles.

“The CRS-2 vehicles allow the delivery of a larger amount of cargo in a single flight,” Shireman said. “Basically, it reduces the total number of missions. That’s important for a couple of reasons. One is it’s more efficient in terms of our crew time, and that’s a precious resource aboard the ISS. When the crew is unpacking and repacking cargo, that’s time they’re not spending doing the research.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.