Last year’s fatal crash of Virgin Galactic’s suborbital rocket plane has delayed the start of the company’s commercial operations at least a year, prompting a change in mindset from a “period of euphoria to a period of real, measurable, but tough progress” as the enterprise backed by Richard Branson enters the second decade since its founding.

Despite the setback, Virgin Galactic’s two-pronged approach to easing access to space for the public and lean budget satellite missions remains intact, but with a few changes to the SpaceShipTwo and LauncherOne vehicles.

Engineers have crafted a device to safeguard against the immediate cause of last year’s mishap — the premature deployment of SpaceShipTwo’s braking feathers — and continue tinkering with the space plane’s rocket fuel mixture.

And Virgin Galactic’s LauncherOne program, sized to carry small satellites into orbit, is growing bigger, both in terms of the rocket’s dimensions and the development effort behind it.

George Whitesides, the company’s chief executive, gave an update on the recovery efforts nearly a year after a crash of the company’s suborbital rocket plane, which killed co-pilot Michael Alsbury and injured the craft’s lead pilot after an in-flight breakup 10 miles above California’s Mojave Desert on Oct. 31, 2014.

“I think that we are moving from sort of a period of euphoria to a period of real, measurable, but tough progress,” Whitesides said last month at the International Symposium for Personal and Commercial Spaceflight in Las Cruces, New Mexico. “I think on the other side of that is real commercial success and really transformative things happening in space.”

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of our full interview with George Whitesides. Become a member today and support our coverage.

Founded in 2004, Virgin Galactic has expanded its staff by 15 to 20 percent since last year’s accident, and Whitesides said the company has never been stronger from a human perspective.

The death of Alsbury, who was an employee of SpaceShipTwo builder Scaled Composites, and the technical setback of the crash was a “tough blow” for Virgin Galactic, Whitesides said.

“But it is one that will not define the company,” he said. “It is one that we must move past, and that we are moving past with determination and spirit.”

Whitesides would not predict when the company would resume SpaceShipTwo flights in an interview with Spaceflight Now, but he said 2016 will be a year full of testing.

The second space-rated SpaceShipTwo vehicle is nearing completion inside a hangar at Virgin Galactic’s operations and test center in Mojave, California.

The next SpaceShipTwo, which has not been named, achieved a milestone called “weight on wheels” in May. Since then, technicians have mated the spacecraft to Virgin’s WhiteKnightTwo carrier jet for the first time and begun installing the oxidizer tank into SpaceShipTwo.

Whitesides said the new version of SpaceShipTwo has few differences from the first vehicle.

“The airframe itself we think is sound, and the propsulion system is sound,” Whitesides said in a presentation at the ISPCS conference last month. “We required very few changes to the vehicle following our test flight accident.”

Federal investigators concluded the technical cause of last year’s crash of the first SpaceShipTwo flight vehicle, named the VSS Enterprise, was the premature unlocking of the craft’s tail feathering system by Alsbury.

Procedures called for the feathering system, which is used to re-orient and slow down the spacecraft during descent, to be unlocked later in SpaceShipTwo’s flight sequence, when the craft is speeding through less air resistance. Instead, Alsbury unlocked the tail booms at eight-tenths of the speed of sound — Mach 0.8 — just seconds after SpaceShipTwo dropped from its huge WhiteKnightTwo mothership and fired its hybrid rocket motor.

Although the flight crew never sent commands to deploy the feathers, the strong aerodynamic forces in the lower, denser part of the atmosphere pushed the unlocked tail booms upward into their re-entry positions, leading to loss of control and the disintegration of the rocket plane.

The NTSB also cited Scaled Composites’ failure to address the risks and consequences of a pilot-induced error, raising chances that a catastrophic accident could be instigated by a single mistake.

In an interview with Spaceflight Now, Whitesides said future SpaceShipTwo flights will include a mechanism that prevents the premature unlocking of the feathers.

“That’s the No. 1 change, and we’ll make sure that’s integrated before we resume test flights,” Whitesides said.

But major programmatic changes are also in store.

The new SpaceShipTwo rocket plane is the first to be manufactured by a Virgin subsidiary named The Spaceship Company, or TSC. Virgin pilots will be at the controls when flights take off again, replacing test pilots from Scaled Composites, SpaceShipTwo’s designer and original builder.

Version two of SpaceShipTwo in the works

The final bond to mate the oxidizer tank with SpaceShipTwo’s airframe is expected before the end of the year, and assembly crews are adding plumbing for the ship’s propulsion system and installing electrical wiring, pneumatics and avionics boxes. Technicians are working on three shifts to complete the vehicle, according to Whitesides.

“We’re working very hard to build this vehicle right, but also build it with pace,” he said.

A new seat design will also debut on the second SpaceShipTwo vehicle, Whitesides said.

Another milestone Whitesides revealed was a fatigue test designed to ensure the suborbital craft’s pressurized cabin can withstand thousands of cycles over its operational life.

“I think we’re getting close to being done with the vehicle,” Whitesides said. “We want make sure that we’re just taking our time, but moving quickly. It’s a balance between those two things. We’re making progress, and 2016 will be filled with lots of testing, and that’s good.”

Engineers have continued test firings of SpaceShipTwo’s hybrid propulsion system during the yearlong grounding, and Virgin Galactic officials expect to use a rubber-based solid fuel called HTPB for the rocket motor when flights resume.

That is a change from the plastic-based fuel used on the ill-fated Oct. 31, 2014, flight, which itself was a switch from rubber fuels on earlier SpaceShipTwo motors. Data on the rocket motor firing in the seconds before last year’s crash — its first in-flight firing — showed it performed as intended.

In a presentation at the ISPCS industry meeting, Whitesides showed video clips of recent rocket tests at Virgin’s Mojave facility burning HTPB, and he told Spaceflight Now that the company will finalize the motor design soon.

Virgin Galactic announced in May 2014 it was going with the alternate plastic-based fuel cartridge, which engineers said offered better combustion stability and more performance than the motor with the original rubber fuel grain, which was developed by Sierra Nevada Corp.

Propulsion work at Virgin Galactic moved in-house with the motor change, and the company ended its partnership with Sierra Nevada.

The hybrid motor works by combining liquid nitrous oxide with pre-packed solid fuel. SpaceShipTwo’s motor generates up to 60,000 pounds thrust, then naturally tails off toward the end of its burn to ease g-forces on passengers.

Once SpaceShipTwo is ready, engineers will put it through a series of tests, first on the ground and then airborne.

“We’ll do all the same stages, but each of those stages will be shorter than they were with the first vehicle,” Whitesides said in an interview. “We’ll do ground testing, then we’ll do captive carry, then glide flights, and then powered flight.”

Whitesides did not say when commercial service could begin with SpaceShipTwo.

Virgin shopping for new LauncherOne carrier aircraft

Virgin Galactic’s other major program, the LauncherOne orbital rocket, is going through its own changes as designers step through a sequence of ground firings of liquid-fueled engines for the air-launched booster.

Officially unveiled in 2012, LauncherOne is one of several privately-funded rockets taking aim at the small satellite market. Lightweight satellites, such as the burgeoning CubeSat movement, currently rely on hitching rides on large rockets as secondary payloads.

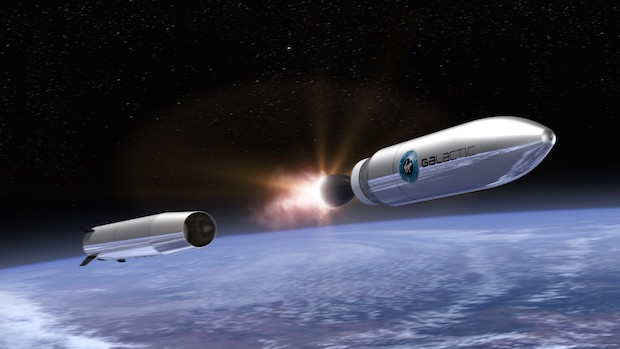

But LauncherOne, like its competitors, is designed with dedicated small satellite launches in mind.

Virgin Galactic announced in September it was equipping the two-stage with rocket bigger fuel tanks, an upgrade that will allow LauncherOne to increase its carrying capacity to sun-synchronous orbit — a perch favored by Earth observation satellites — from 120 kilograms (264 pounds) to 200 kilograms (440 pounds).

The launcher program’s affordability goal remains the same, with each LauncherOne flight pegged to cost customers less than $10 million. That means the price-per-kilogram goes down, officials said.

A survey of the small satellite market in the coming years indicated LauncherOne’s original capability was not enough for many prospective customers, according to Steve Isakowitz, Virgin Galactic’s president.

“Fortunately, we had the kind of design, through the engines that we were building, that without actually making any changes to the engines themselves, but just by stretching the vehicle, we were able to get a vehicle that essentially could double its performance for about the same price point,” Isakowitz said Oct. 14.

Speaking at a NASA press conference announcing a $4.7 million launch contract between the space agency and Virgin, Isakowitz said the upsized rocket will require a different carrier aircraft. Virgin initially planned to deploy the rocket from the belly of WhiteKnightTwo in similar fashion as SpaceShipTwo.

“We are going to be flying on a commercial aircraft, and we do expect, in a coming short while, to announce exactly what aircraft we are going to be flying on,” Isakowitz told reporters.

LauncherOne’s development is headquartered in Long Beach, California, at a 150,000 square foot facility currently being outfitted for rocket assembly work.

Virgin Galactic has released videos showing LauncherOne’s first stage engine, called the NewtonThree, firing up on a Mojave test stand for up to 90 seconds. A single NewtonThree engine, powering up to 73,500 pounds of thrust, will be LauncherOne’s first stage propulsion, and a 5,000-pound thrust engine will be on the second stage.

The company says it has also completed gas generator tests on the second stage NewtonFour powerplant.

Both engines are pump-fed and consume kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants, and their development follows Virgin demonstration firings of more basic pressure-fed engines.

Whitesides said LauncherOne is primarily an internal development, but Virgin selected Barber-Nichols Inc., a key supplier on SpaceX’s Merlin rocket engine and Aerojet Rocketdyne’s RS-68 engine, to build turbomachinery for the Newton engine series.

“It’s almost entirely in-house,” Whitesides said. “We announced that we’re using Barber-Nichols for the turbopumps, and there are bits and pieces to the vehicle that are from suppliers, but the main systems are internal.”

The air-launch concept means LauncherOne missions are not constrained at specific launch sites like terrestrial-based rockets. Virgin is evaluating staging LauncherOne flights from the U.S. West Coast and East Coast, including the former space shuttle landing strip at Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Will Pomerantz, vice president for special projects at Virgin Galactic, said the first test flights with LauncherOne could be based out of Mojave, a location where Virgin has significant experience and a large footprint.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.