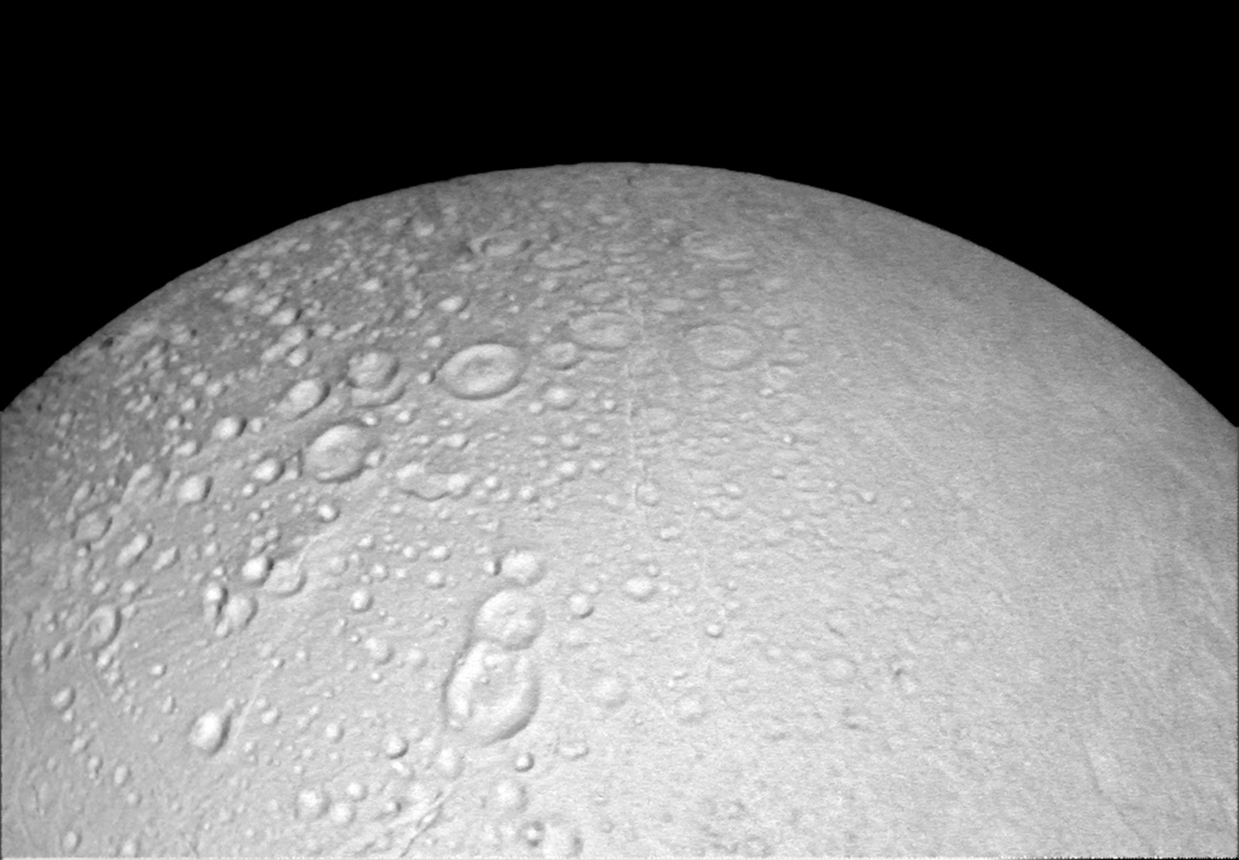

Rushing past Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus at dizzying speed, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft took its first pictures of the captivating object’s sunlit north pole last week, revealing cracks in the moon’s frozen crust and crater fields extending dozens of miles across.

In its final two years orbiting Saturn, Cassini flew by Enceladus on Oct. 14 at a distance of 1,142 miles (1,839 kilometers), yielding the best ever views of the moon’s north pole, which was mired in darkness earlier in the probe’s mission.

Scientists say Enceladus harbors a global ocean deep beneath the moon’s outer frozen layer, and vents emanate from cracks near its south pole, launching material from the subsurface sea into space. Cassini’s next flyby Oct. 28 will dip deeper into the plumes than ever before to sample the stuff.

But the mission’s Oct. 14 encounter focused on the north pole.

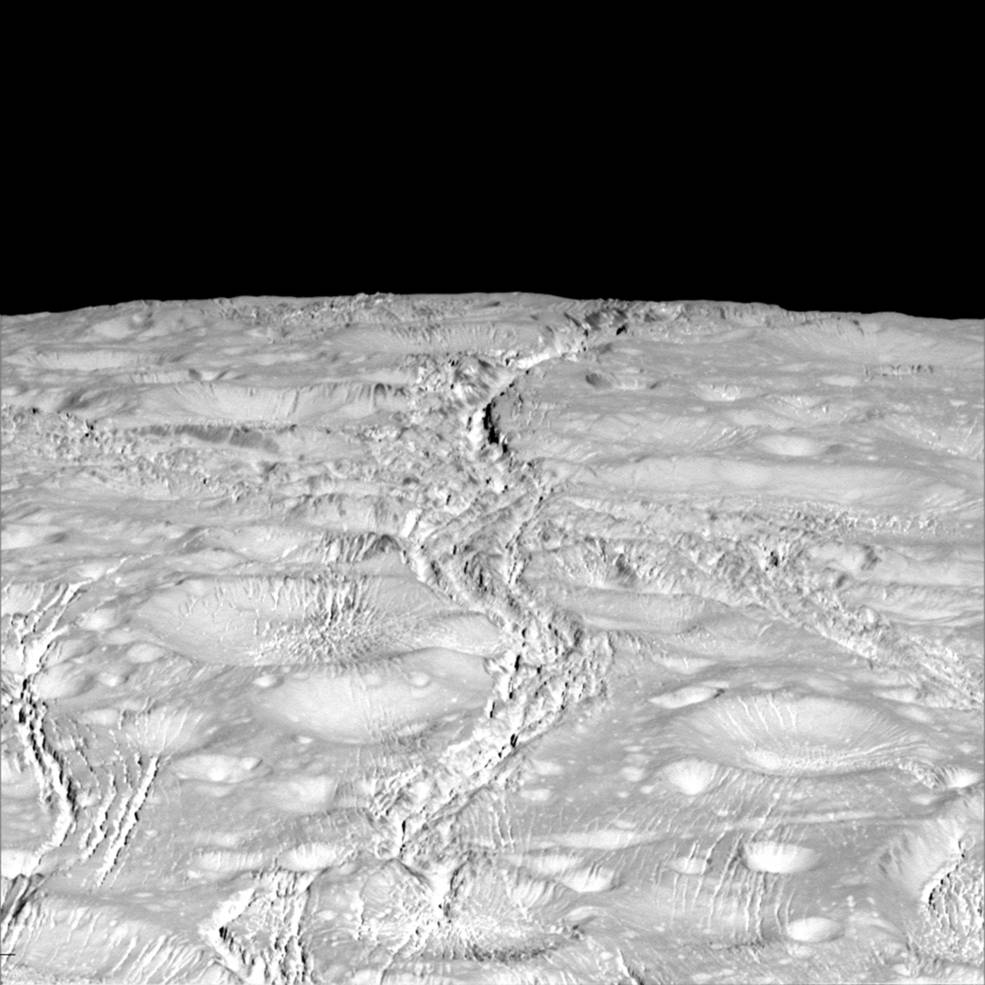

The images show craters scattering Enceladus’ northern polar plains, including a set of three connected impact basins scientists have dubbed the moon’s “snowman” feature.

A network of thin cracks — already observed elsewhere on Enceladus — extend across the northern hemisphere, the flyby discovered.

“The northern regions are crisscrossed by a spidery network of gossamer-thin cracks that slice through the craters,” said Paul Helfenstein, a member of the Cassini imaging team at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. “These thin cracks are ubiquitous on Enceladus, and now we see that they extend across the northern terrains as well.”

One of the brightest objects in the solar system, Enceladus is about the size of the U.S. state of Arizona with surface temperatures as cold as minus 330 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 201 degrees Celsius). It completes an orbit of Saturn in less than 33 hours.

Scientists hope to learn whether the moon’s north pole shows signs of recent geologic activity like Enceladus’ southern hemisphere.

Earlier this year, researchers announced that hydrothermal vents may be present on the floor of Enceladus’ underground ocean, raising hopes the moon could host environments habitable by microbial life. The Oct. 28 flyby — at a distance of a mere 30 miles (49 kilometers) — is geared toward revealing more about what is going on below Enceladus’ frozen veneer, collecting data that could shed light on the suspected subsurface hydrothermal activity.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

“We’ve been following a trail of clues on Enceladus for 10 years now,” said Bonnie Buratti, a Cassini science team member and icy moons expert at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “The amount of activity on and beneath this moon’s surface has been a huge surprise to us. We’re still trying to figure out what its history has been, and how it came to be this way.”

A final visit to Enceladus is planned for Dec. 19, then the plutonium-powered Cassini orbiter will shift its orbit for a final series of flybys of Saturn’s largest moon Titan before diving between the gas giant’s outer atmosphere and famous rings for the first time.

Ground controllers plan to guide Cassini into Saturn on Sept. 15, 2017, to end the mission before it runs out of fuel, completing a 13-year tour at the ringed planet.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.