NASA announced Wednesday it is joining a chorus of companies pushing for easier access to space, awarding $17.1 million in contracts to three firms developing new launchers tailored for lifting lightweight satellites into orbit.

None of the rockets have flown yet, but NASA plans to put dozens of small CubeSat-class satellites on the new launchers for three test flights by April 2018.

The three Venture Class Launch Services contract winners — Firefly Space Systems, Rocket Lab USA and Virgin Galactic — are developing rockets that industry officials promise will deliver small satellites into low Earth orbit for less than $10 million.

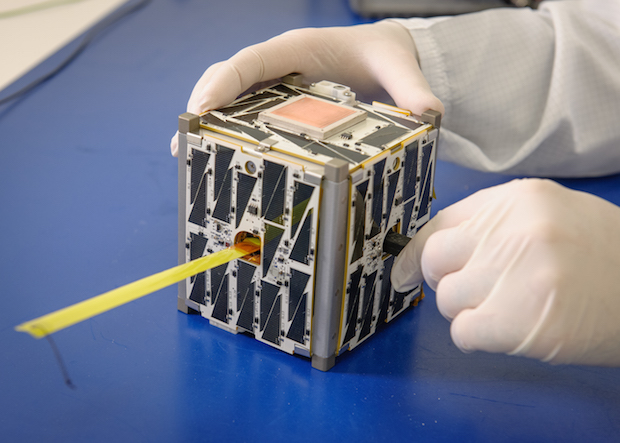

The rockets are sized to carry up small spacecraft like CubeSats on a dedicated ride. CubeSats currently must launch aboard larger rockets with a much larger primary payload, which dictates the mission’s final orbit and launch schedule.

“Until today, CubeSats have basically depended on other launch vehicles to obtain their rides into space as piggybacks — hitchhikers basically,” said Garrett Skrobot, mission lead for NASA’s Educational Launch of Nanosatellites, or ElaNa, program at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. “We’ve been called coach class to space.”

CubeSats come in different sizes based on a standard cube-shaped form factor 3.9 inches (10 centimeters) on a side. For more capability, designers can add more cubes to spacecraft — a three-unit CubeSat is about the size of a shoebox — while keeping the basic CubeSat mold.

Such satellites are made by university students, government agencies and a growing number of startup space companies for experimental, research and commercial applications.

NASA put out a request for proposals earlier this year, seeking bids from commercial launch companies developing small-scale rockets to tap into the growing small satellite market.

The space agency said Wednesday it awarded Firefly Space Systems of Cedar Park, Texas, a $5.5 million contract, Los Angeles-based Rocket Lab USA a $6.9 million launch deal, and Virgin Galactic of Long Beach, California, a $4.7 million contract.

“We bought three demonstration flights,” said Mark Wiese, head of the flight projects office in NASA’s Launch Services Program at Kennedy, which is responsible for booking rocket rides for the agency’s science missions. “These three companies, before April 2018, will demonstrate their (rockets) and will give the Launch Services Program insight and help open the door for the scientific community to help bring new smaller payloads forward.”

Skrobot said NASA will place between 100 pounds and 200 pounds (45-90 kilograms) of CubeSats on each of the three demonstration flights by Firefly, Rocket Lab and Virgin Galactic. The NASA-sponsored test launches will target orbits less than 280 miles (450 kilometers) in altitude, he said.

NASA has a backlog of more than 50 CubeSats built by agency research centers and university partners waiting for a launch assignment, and there are only a few openings per year to fly the satellites as secondary passengers on larger rockets, such as the Atlas and Delta launchers.

CubeSats are also carried to the International Space Station by SpaceX and Orbital ATK supply ships, but the space station’s orbit is not suited for many CubeSat applications.

Small rockets sized for delivery of CubeSats into orbit can haul up large constellations of spacecraft directly to their desired destination. No incumbent launch company is working on such a class of boosters.

“Flying piggyback or secondary basically meant we had to go where the primary (payload) went,” Skrobot told repoters Wednesday. “We were not able to select our orbits. We had to build our science around those particular orbits, or sacrifice some of the science. However, today with the new Venture Class Launch Systems, this is no longer the case. The CubeSats will now be the primary payload on these vehicles. We can say now we are riding first class.”

Firefly Space Systems is led by Thomas Markusic, a former manager at SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic who previously held posts in NASA and the U.S. Air Force. The two-stage Firefly Alpha booster burns a mixture of liquid oxygen and rocket-grade kerosene, and it is designed to put a 440-pound (200-kilogram) payload into sun-synchronous orbit, according to the company’s website.

Maureen Gannon, Firefly’s vice president of business development, said the company targets weekly launches after the Alpha booster’s debut in 2018. Operational missions will go for $8 million per launch, she said.

She said the NASA contract award is “a vital step in the much larger mission of growing not only Firefly Space Systems, but the small launch industry as a whole.”

Suborbital test flights by Firefly will begin in 2017 from Kennedy Space Center’s launch pad 39C, a facility inside the footprint of pad 39B at the Florida spaceport, Gannon said.

“In 2018, our company will begin launching orbital missions, eventually ramping up to 50 missions per year,” Gannon said. “We will be offering weekly scheduled access to low Earth orbit and allowing customers such as NASA to pick and choose the flights that work best for them.”

Gannon said Firefly was not ready to announce a location for its orbital launches.

Rocket Lab’s Electron rocket is priced at $4.9 million per mission. The higher value of the company’s NASA contract is based on the space agency’s more stringent requirements over a typical commercial mission, according to Peter Beck, Rocket Lab’s founder and CEO.

“Cost is only half of the problem here,” Beck said Wednesday. “The other half, of course, is being able to fly frequently and being able to fly on schedule. Rocket Lab has gone to extreme efforts to ensure that is a reality.”

Based in Los Angeles but with production and launch facilities in New Zealand, Rocket Lab says it is on track for its first test flight of the Electron booster in 2016.

Beck said Rocket Lab is considering basing some of its missions from Kennedy’s pad 39C, but the company has no firm agreement yet. The company says its NASA flight under the agreement announced Wednesday will be Electron’s fifth mission, scheduled in late 2016 or early 2017.

Fueled by a mixture of liquid oxygen and kerosene, the two-stage Electron can put a 330-pound (150-kilogram) satellite into orbit 310 miles (500 kilometers) above Earth, according to Rocket Lab’s website.

The rocket is about 3.3 (1 meter) in diameter and stands approximately 66 feet (20 meters) tall. The booster is built around the Rutherford engine, which is driven by electric motors instead of gas generators.

With its major components fabricated in a 3D printer, the Rutherford engine will power both stages of the Electron. Nine Rutherford powerplants will be on the first stage, producing more than 140,000 pounds of thrust. One 5,000-pound thrust Rutherford engine will be on the second stage.

Rocket Lab is backed by venture capital shops from Silicon Valley and New Zealand, including firms which led investment in Skybox Imaging, a growing Earth observation satellite company later acquired by Google.

Lockheed Martin will also make a strategic investment in Rocket Lab, the company announced in March.

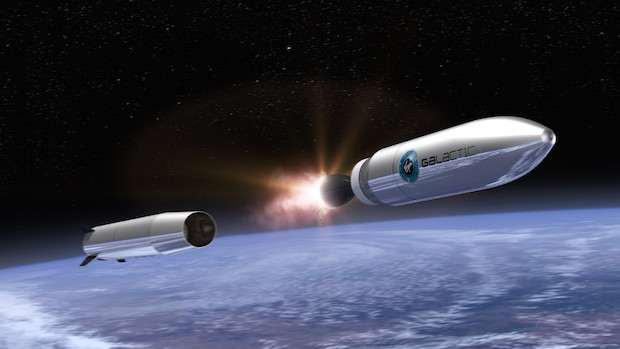

Virgin Galactic’s LauncherOne rocket can deploy 440 pounds (200 kilograms) of cargo into sun-synchronous orbit for less than $10 million per flight, according to company leaders.

Launched from the belly of an airplane over the ocean, the two-stage LauncherOne burns liquid oxygen and RP-1 kerosene fuel, the same fuel cocktail driving the Firefly and Rocket Lab boosters.

LauncherOne is the second large space project undertaken by Virgin Galactic, which was founded by Richard Branson in 2004 to carry space tourists and researchers on brief suborbital jaunts into space. Virgin’s SpaceShipTwo rocket plane is preparing to resume test flights after a fatal crash last year halted preparations for the ship’s commercial debut.

Virgin Galactic’s LauncherOne program is headquartered at a factory in Long Beach.

“I think it is important to see that the government is participating, and participating in a way that reflects the class of payloads that are being flown,” said Steve Isakowitz, president of Virgin Galactic. “Sometimes you can turn an inexpensinve launch vehicle into an expensive one if you levy too many requirements on it. I think nasa is taking about the right touch on this in looking to get these payloads access to space for the best price and the best availability.”

Isakowitz said LauncherOne’s first flights will likely be based from Virgin Galactic’s test site in Mojave, California, but the air-launch design allows future missions to stage from other locations, including KSC’s shuttle runway.

Wiese said NASA did not specify a launch site in its requirements for the Venture Class Launch Services winners, but the agency received a discount from Virgin Galactic and Firefly for taking a chance to fly on one of their rockets’ first flights.

“We’re definitely going after a high-risk approach here,” Wiese said. “The CubeSats represent that high risk-tolerant payload, which is perfect for demonstration on a first flight.”

Wiese said the contracts are structured to allow NASA “to step back a little bit and make sure the government gets out of the way and doesn’t inhibit the commercial solutions these companies are trying to bring forward.”

There are no other competitions planned by NASA in the lightweight Venture Class Launch Services market, but officials foresee placing more valuable payloads such rockets in the future.

“But we’re definitely going to get insight, so that when we do go forward and try to procure a launch service for a low risk-tolerant spacecraft, we’re one step ahead of the game in trying to certify them to make sure they can give us safe access to space,” Wiese said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.