NASA officials are waiting to see if Congress adds funding to the agency’s budget next year to kick-start development of a new four-engine upper stage for the Space Launch System, an upgrade that would allow the mega-rocket to loft heavier cargoes into deep space.

The new rocket component, called the Exploration Upper Stage, could be developed in time for the Space Launch System’s second flight in 2021, which will be the first time the launcher will carry a crew inside an Orion capsule.

The 2021 flight is named Exploration Mission-2 and would take astronauts around the moon on the farthest flight by humans in history.

“Our goal is to introduce it for EM-2, the flight in 2021,” said Bill Hill, NASA’s deputy associate administrator for exploration systems development. “We would like to do that for several reasons. One is it gets it introduced earlier, and two, we wouldn’t have to human-rate what we’re calling the interim cryogenic propulsion system, which is a modified Delta cryogenic second stage.”

But Hill said the White House’s proposed budget for the behemoth booster next year is not sufficient to start full-scale work on the larger rocket stage, raising concerns the 2021 launch may require human-rating the Delta 4-based interim single-engine upper stage, an effort NASA officials previously said will cost about $150 million.

The Obama administration requested $1.356 billion for the Space Launch System in fiscal year 2016, which begins Oct. 1.

Hill said the upper stage upgrade would not be complete in time for the EM-2 crew mission in 2021 if the $1.356 billion budget is enacted.

“It’s not quite there,” Hill said in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “It would have to be probably later at that level.”

NASA officials have said adding funding above the White House’s budget request will not bring forward the first unpiloted test flight of the SLS, which will be ready no later than November 2018. But managers admit they need more money to complete the Exploration Upper Stage for the first crewed flight in 2021.

The first SLS test flight in 2018 will use the interim cryogenic upper stage modeled on the second stage of United Launch Alliance’s Delta 4 rocket. It is powered by a single Aerojet Rocketdyne RL10 engine burning a super-cold mixture of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen.

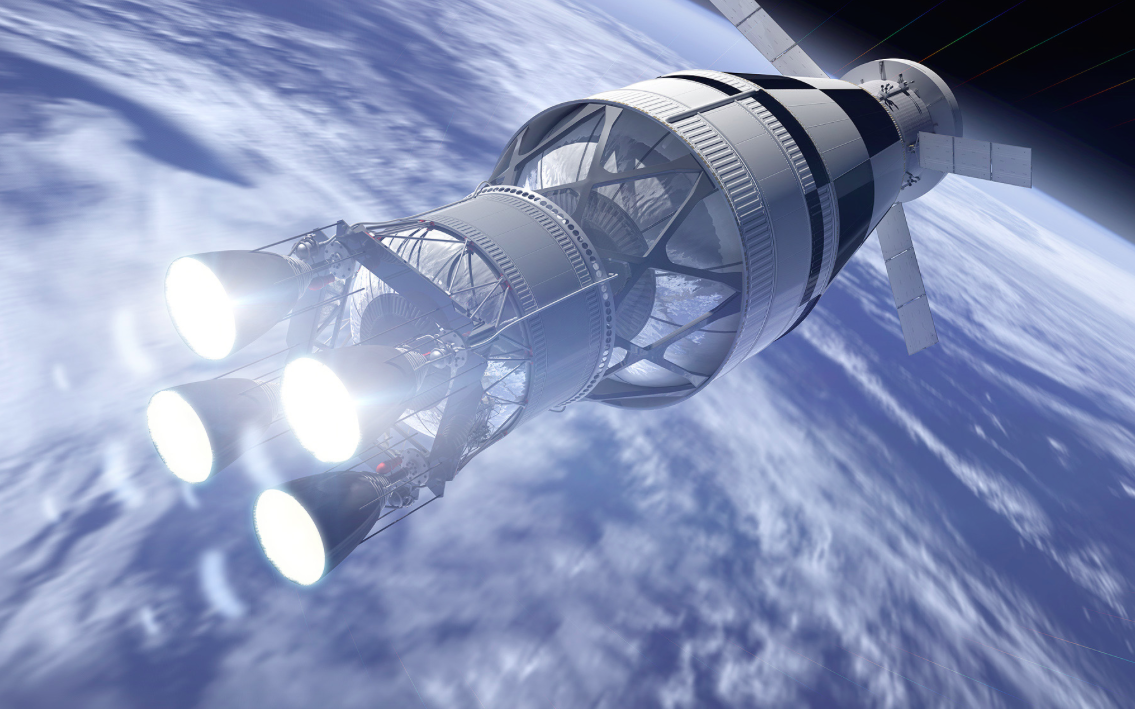

The Exploration Upper Stage will feature four RL10 engines and measure 27.6 feet, or 8.4 meters, across. That is the same diameter of the Space Launch System’s core stage, which is driven by four RS-25 main engines repurposed from the space shuttle program.

NASA has a contract prepared with Boeing, the prime contractor for the SLS core and upper stages, to work on the upgraded Exploration Upper Stage.

“We have a contractual vehicle to do it, but we haven’t enabled that,” Hill said. “We’re still looking, depending on how appropriations go this year, whether we get appropriations or whether we get a continuing resolution, and whether it’s a three-month continuing resolution or a full-year might make a difference on whether we can start this year or not.”

Congress has until the end of September to pass a spending bill to fund the government in fiscal year 2016. Barring an agreement on a new budget, lawmakers could pass a continuing resolution, which would fund programs at or near 2015 levels.

The House and Senate have passed drafts for NASA’s 2016 budget, both with extra money for the heavy-lift rocket. But the chambers would have to iron out the differences before sending a final bill to the White House for President Obama’s signature.

The House version proposes $1.85 billion for the Space Launch System in 2016, including $50 million devoted to an enhanced upper stage for the rocket. The Senate passed a budget with $1.9 billion for the SLS program, with $100 million of that earmarked for the Exploration Upper Stage.

Advocates for developing the new upper stage sooner say the three-year gap between the first SLS test flight and the start of crewed missions is the best time to add the upgraded propulsion unit.

Construction crews at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida will have to raise the height of access arms and umbilical platforms on the rocket’s mobile launch platform to accommodate the taller upper stage.

The SLS will stand 321 feet tall in its initial “Block 1” configuration. With the enlarged second stage, the huge rocket’s “Block 1B” version will top out at 365 feet, roughly the same height as the Saturn 5 moon rocket. NASA eventually wants to add more powerful strap-on boosters to the rocket to haul up even bigger loads to Mars.

“We have got time between EM-1 and EM-2 to do the modifications we need to do for the mobile launcher because it moves Orion up,” Hill said. “We basically have to cut it near the top, move everything up, and then re-bolt it together.”

Hill said NASA has no concerns with putting humans on the first flight of a new upper stage.

“We did the same thing with shuttle,” Hill said. “We may minimize the crew, although we’re trying to hold to a crew of four right now. We could go down to two, but we really want to keep it to a crew of four. Right now, we believe we can certify it and do everything on the ground to prove that it is safe to fly humans on it.”

Boeing plans to manufacture the Exploration Upper Stage with the same tooling built for the SLS core stage at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans.

Officials initially planned to power the upper stage with a J-2X engine, a modernized powerplant based on the J-2 engine designed in the Apollo era. But managers decided the J-2X, which had roots in the canceled Constellation moon program, was overpowered for the job and sidelined the engine after a series of hotfire ground tests.

NASA spent more than $1.4 billion on the J-2X engine from 2006 through 2014, an agency spokesperson said.

“We optimize (the Exploration Upper Stage) at about 120,000 pounds thrust, and the J-2X is designed for about double that,” said Todd May, who led NASA’s Space Launch System program from its inception until last month, when he took over as deputy director of the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama.

“The interesting thing though is that just after we finished the test program for J-2X, we ran it at 150,000 pounds (thrust), and it was fairly stable at 150,” May said. “It was a contender, and it still is, when you get the big boosters on and you need a bigger engine for the Mars-type missions.”

Aerojet Rocketdyne, NASA’s SLS engine builder, disassembled the three J-2X test engines and put the parts in storage. NASA has not ruled out restarting the J-2X development line for human missions to Mars, but such expeditions are decades away.

For now, NASA managers say the four RL10 engines are enough to meet NASA’s requirements for human voyages around the moon, in a region officials dub “cis-lunar space.” The first two SLS/Orion missions in 2018 and 2021 will target a distant lunar retrograde orbit about 44,000 miles, or 70,000 kilometers, from the moon.

The basic SLS configuration set to launch in 2018 can haul 77 tons (70 metric tons) into low Earth orbit, or about 28 tons (25 metric tons) on a trajectory toward the moon. With the bigger four-engine upper stage, the rocket can deliver nearly 50 percent more mass to those destinations, giving designers margin to install pressurized habitats and secondary payloads to construct a mini-space station in deep space and conduct research around an asteroid NASA hopes to retrieve and tug back near the moon.

Each RL10 engine can generate nearly 25,000 pounds of thrust. Variants of the powerplant currently fly on the Atlas 5 and Delta 4 rockets.

“They are basically off-the-shelf engines, which had some had some attractiveness in availability, affordability and reliability,” said Benjamin Donahue, an engineer at Boeing who works on the Exploration Upper Stage.

But NASA says it needs to give Boeing the green light to complete the design and development of the upper stage soon to have it ready by 2021. Otherwise, NASA may have to order a second interim Delta 4-based upper stage and pay to certify it for astronaut passengers, then test the upgraded stage on the third SLS flight in the early 2020s.

“If you could avoid that … and have that money go toward the stage we’d like to fly for a longer period of time, then you get a little bit more bang for the buck,” May said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.