A Japanese HTV cargo craft is being prepped for liftoff Wednesday with a much-needed shipment of provisions for the International Space Station’s six-person crew after a spate of failures strained the orbiting lab’s supply chain with Earth.

Packed with 9,522 pounds of cargo, Japan’s fifth H-2 Transfer Vehicle is set for launch at 1150:49 GMT (7:50 a.m. EDT) from the Tanegashima Space Center in southern Japan.

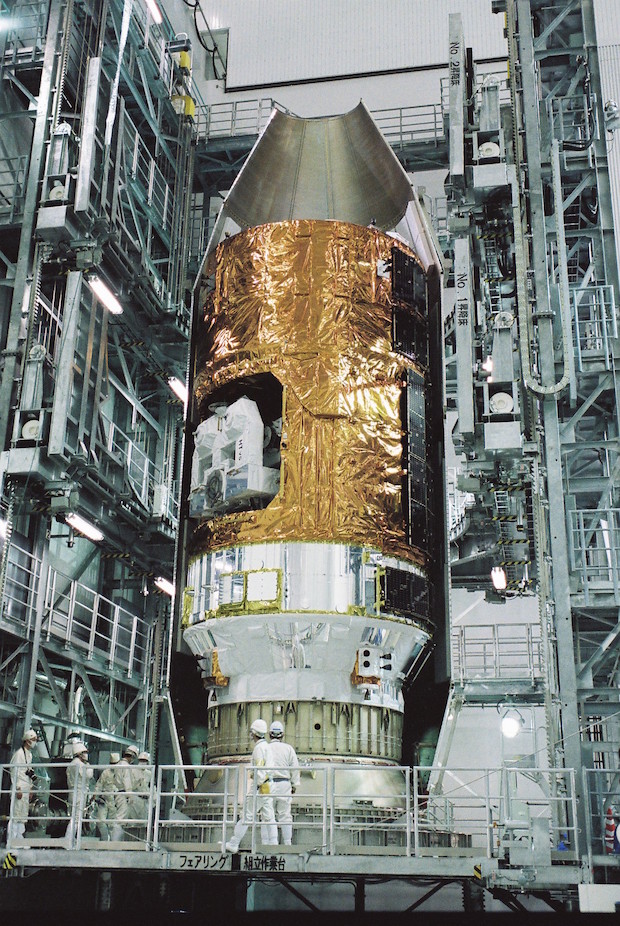

About the size of a touring bus, the automated supply ship is shrouded in the nose of a Japanese H-2B rocket that rolled out to the launch pad at Tanegashima early Wednesday, local time.

Also known as Kounotori 5, the Japanese word for white stork, the cargo carrier is loaded with food, spare parts, science experiments, a new kitchen galley, and a cosmic ray telescope designed to probe dark matter from a mounting plate outside the space station.

Launch crews with Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, the H-2B rocket’s builder and commercial operator, planned to load thousands of gallons of super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants into the 186-foot-tall rocket Wednesday to power the launcher’s first and second stage engines.

Control of the countdown will pass to an automated sequencer in the final minutes before liftoff, which is set for 8:50 p.m. local time Wednesday in Japan.

The rocket’s twin LE-7A main engines will ignite about five seconds before liftoff, and the H-2B’s four monolithic strap-on solid rocket boosters will fire to propel the rocket off the launch pad at Tanegashima.

The orange and black launcher will turn southeast and accelerate over the Pacific Ocean, shedding the four strap-on motors about two minutes into the mission. The clamshell-like aerodynamic fairing enclosing the HTV supply ship will jettison at T+plus 3 minutes, 40 seconds.

The twin-engine first stage will cut off at T+plus 5 minutes, 47 seconds, following by stage separation seven seconds later, then ignition of the second stage’s LE-5B powerplant for a burn slated to last more than eight minutes to inject the massive cargo carrier into orbit.

Deployment of the HTV is expected at T+plus 15 minutes, 11 seconds, according to information released by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency.

Wednesday’s launch kicks off a five-day pursuit of the space station, in which the uncrewed cargo craft will adjust its orbit to match the path of the mammoth research complex.

The HTV’s final laser-guided rendezvous sequence Aug. 24 will culminate in its capture by the space station’s robotic arm, which will be controlled by flight engineer Kimiya Yui, the first time a Japanese astronaut will be responsible for snaring an incoming HTV cargo vessel.

The robotic arm should grapple the free-floating supply ship around 1055 GMT (6:55 a.m. EDT) Monday.

The fifth HTV mission comes two years after the Japan’s last resupply flight to the space station, and NASA managers and the crew aboard the outpost will closely watch Wednesday’s liftoff after recent launch mishaps grounded the research lab’s other three logistics vehicles.

A launch failure in Virginia destroyed a commercial Cygnus cargo craft owned by Orbital ATK in October 2014, then a Russian Progress refueling freighter tumbled out of control in orbit after a botched separation from its Soyuz booster in April.

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket broke apart minutes after liftoff from Cape Canaveral on June 28 on a resupply run to the space station.

Russia’s Progress cargo missions resumed in July, with another Progress launch due Oct. 1, but Orbital ATK and SpaceX logistics flights remain grounded. Orbital ATK booked an Atlas 5 rocket to launch its next Cygnus supply ship Dec. 3.

NASA expects the next SpaceX mission to the space station to be ready for launch in December as well, but the agency has asked SpaceX for the resupply flight not to be first in line when the Falcon 9 rocket returns to flight, according to Mike Suffredini, NASA’s International Space Station program manager.

While space station managers typically like to keep a six-month stock of supplies on the complex, the crew had to dip into some of the reserves after losing three cargo shipments in eight months.

Now the space station has about three months of supplies, assuming no more missions.

“We need to fly HTV to continue to operate on-board, so it’s of significant need,” Suffredini said in an interview Monday. “We’ve got resources, I think, into November right now, so this (HTV mission) give us resources into the next year.”

The crew has two Russian Soyuz landing craft docked to the space station as lifeboats, but Suffredini said an evacuation would not be discussed until at least mid-October, when the supply stockpiles would reach a 45-day critical limit, triggering planning for an orderly return of the astronauts and cosmonauts living on the research lab.

But with a Russian Progress mission set for launch before mid-October, Suffredini said a failure on the HTV flight would not automatically create an urgency to plan for evacuation or reduction of the size of the crew.

“We’re in good shape right now, but if for some reason HTV didn’t get here, we get pretty low on certain consumables probably in late September, early October timeframe,” NASA astronaut Scott Kelly told CBS News on Monday in an interview from the space station. “I’m sure we would figure out ways to bridge the gap on those things. … But if for some reason HTV gets delayed for a significant amount of time or something else happens, we do run into some issues.

“We’ve been pretty good about dealing with those things, and I’m sure we will, we would figure out a way around it, but it is a very important launch for us coming up.”

In the aftermath of June’s SpaceX failure, NASA added critical spares for the space station’s water filtration system and spacesuits to the HTV’s cargo manifest.

“There is some hardware we needed to re-arrange to put on this flight to buy us back some capability (after the resupply mission failures),” Suffredini told Spaceflight Now. “We have a pump that we lost that we’re flying on the HTV. The big thing was we needed some filtration beds for the water processor, we call them multi-filtration beds, and there are two of them. We lost them on Orbital, and we lost another set on SpaceX, so they’re really urgent. The team has really turned on to get those things refilled and to get them to Tanegashima in time.”

The space station’s closed-loop life support system produces fresh water from processed urine, condensate and other waste water, but Suffredini said processed condensate from the space station’s atmosphere contains a higher than expected abundance of a chemical called dimethylsilanediol, which clogs up the filtration beds.

“So it’s not that the system can’t handle it or produce safe drinking water,” Suffredini said. “It’s that there so much of this compound in the air that it causes us to get full with our beds earlier than we expected.”

In the meantime, ground controllers have commanded the water processing system to trap condensate but not process it until the new filtration beds arrive.

Kounotori 5’s 4.7-ton cargo load includes:

- 3,101 pounds of crew supplies, such as food, clothing and pantry items

- 2,753 pounds of scientific utilization hardware for NASA and JAXA

- 1,915 pounds of vehicle hardare, including spare parts and a galley

- 172 pounds of spacewalk equipment, such as a rescue jetpack and spacesuit parts

- 119 pounds of computer resources, including printers, batteries and chargers

A 1,460-pound experiment package fastened inside the HTV’s unpressurized cargo hold will be mounted outside the space station’s Japanese Kibo lab module to study cosmic ways.

Led by Japanese scientists, the Calorimetric Electron Telescope, or CALET, instrument will search for sources of high-energy cosmic rays in local regions of the Milky Way galaxy. Researchers hope data from the sensor will include signatures of dark matter, the unexplained material that makes up more than one-quarter of the universe.

“To ascertain the existence of dark matter, electromagnetic waves flying about in space, as well as cosmic rays and high energy gamma rays (both rays hold energy with much higher than these of ultraviolet rays and X-rays) should be closely examined,” explains an overview of the CALET experiment on JAXA’s website.

Scientists expect the cosmic ray detector to operate between two and five years.

The space station’s robotics system will transfer the CALET instrument and its carrying pallet out of the HTV’s external cargo hold in late August and install three aging research payloads in its place inside the HTV.

The three experiment packages, all at the end of their lives, will burn up inside the HTV after its departure from the space station in late September.

Four more HTV missions are on the books after Wednesday’s launch, bringing Japan’s total contribution to nine resupply flights through 2020.

Japan pays its share of the International Space Station’s annual operating costs through a barter agreement with NASA instead of through cash exchanges. The arrangement allows Japan to meet its payment requirements through cargo services with the HTV.

“We have nine (HTVs) total, seven in the first batch, and two more with the most recent barter, and we’re busy bartering for more HTVs beyond 2020,” Suffredini said.

Officials want to keep the HTV flying through the life of the space station because it is the only supply craft capable of carrying up large research racks to be placed inside the outpost’s laboratory modules.

With the retirement of the space shuttle and Europe’s Automated Transfer Vehicle, the Japanese craft is the largest logistics vehicle currently servicing the research complex.

“It’s got a very large volume inside so we utilize it quite a bit for up-mass, but also for trash,” Suffredini said. “We fill it and we stuff it when we’re done, and when we close the hatch, it’s completely full all the way to the hatch, so it’s very, very good in terms of taking off trash.”

The next HTV mission is set for late 2016, followed by flights about once per year through the rest of the decade.

“HTV is on the larger side for a resupply vehicle, which is good,” Suffredini said. “You don’t fly as many flights with a larger vehicle, so that’s significant. It’s pressurized volume is very big. It will be the only vehicle that will carry racks to orbit, so that’s a unique role that it will have for us in the future. We intend to retain that capability because nobody else can do it.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.