Backed by a fresh capital infusion and regulatory rights to a valued slice of satellite communications spectrum, the space-based Internet company OneWeb has contracted with Arianespace and Virgin Galactic to deploy hundreds of refrigerator-sized spacecraft around Earth.

OneWeb’s deal with Arianespace covers 21 launch orders for the Russian-made Soyuz rocket, most of which will blast off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Arianespace’s agreement with OneWeb also includes options for five more Soyuz flights and three launches of the next-generation Ariane 6 rocket.

Arianespace’s missions will build out OneWeb’s constellation, carrying up to 700 satellites on the initial 21 Soyuz launches. An Arianespace spokesperson said each Soyuz flight will haul between 32 and 36 satellites, depending on the craft’s final design.

The value of Arianespace’s contract is more than $1 billion, pushing the launch firm’s total backlog above $6 billion, officials said.

At least 15 of the 21 firm Soyuz launches will take off from Kazakhstan, according to Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, with the rest originating from the French-run Guiana Space Center in South America or other launch sites in Russia.

Roscosmos, Virgin Galactic and OneWeb hailed the rocket procurement the largest commercial launch purchase in history. It bests a SpaceX contract with Iridium signed in 2010 valued at nearly $500 million, a deal SpaceX chief executive Elon Musk then proclaimed as the biggest booster buy to date.

“This contract is the largest in the history of the provision of launch services,” said Igor Komarov, head of Roscosmos, in a statement. “And the choice of Soyuz is evidence of the high competitiveness of the Russian rocket and space technology.”

Each OneWeb satellite will weigh less than 150 kilograms — about 330 pounds — and will ride into space on a specially-designed dispenser.

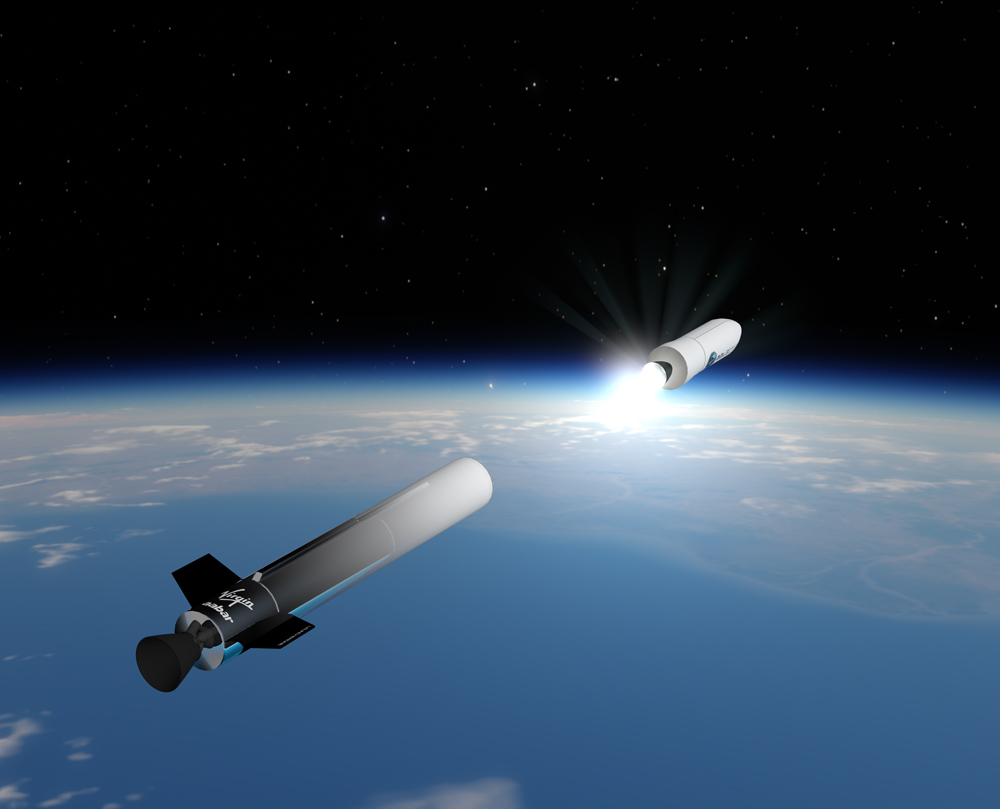

Virgin Galactic’s air-launched LauncherOne vehicle, which is still in development and could fly in 2016, was also awarded 39 launches by OneWeb to replenish the company’s satellite fleet as old satellites stop working. LauncherOne will haul up one satellite at a time, and Virgin Galactic expects to base most of the rocket’s operations at Spaceport America in New Mexico after initial tests from the company’s headquarters in Mojave, California.

The value of Virgin Galactic’s contract was not disclosed, but the company is targeting less than $10 million per LauncherOne mission.

OneWeb signed the launch contracts June 25 in conjunction with an announcement the company has raised $500 million from companies in Europe, the United States, India and Mexico.

The investment puts OneWeb on track to continue working on spacecraft and ground terminals for the global Internet network, and will propel the startup toward attracting additional funding needed to complete development of the system, officials said.

“The dream of fully bridging the digital divide is on track to be a reality in 2019,” said Greg Wyler, founder of OneWeb, in a statement accompanying the funding announcement. “Together with our committed and visionary founding shareholders we have the key elements in place: regulatory, technology, launches, satellites, as well as commercial operators in over 50 countries and territories.”

Founded by Wyler and based in Britain’s Channel Islands, OneWeb plans to deploy the satellites in 20 orbital planes 1,200 kilometers (745 miles) above Earth, spreading the platforms around the world to enable global broadband Internet coverage.

Before OneWeb, Wyler launched O3b Networks, another satellite Internet company focused on backhaul services to rural areas, remote islands and other hard-to-reach regions. Google, HSBC and satellite operator SES were the big investors in O3b, which operates 12 satellites in orbit.

OneWeb announced a partnership with Airbus Defense and Space to build 900 satellites for the company’s broadband-via-satellite scheme, including ground and in-orbit spares. The basic constellation required for full service is 648 satellites, according to OneWeb.

The first satellites will be ready for launch by the end of 2017, initially going into an orbit 500 kilometers — about 300 miles — above Earth before using on-board thrusters to raise their altitude to join the OneWeb fleet.

Airbus is one of the companies OneWeb revealed as a new financial backer last week, along with Intelsat, a competitor to SES, which is a main investor in O3b. New Delhi-based Bharti Enterprises, Hughes Network Systems — a subsidiary of EchoStar Corp. — Coca-Cola and Totalplay, a company owned by Mexican billionaire Ricardo Salinas Pliego, are also behind OneWeb.

Richard Branson’s Virgin Group and wireless tech giant Qualcomm already revealed their participation in the OneWeb venture.

OneWeb aims to beam wifi and mobile data service around the world by 2019, reaching homes, businesses, hospitals, schools, oil rigs, ships, airplanes and trains. It works by broadcasting a signal to a hotspot that customers can install on their roofs.

“We are committed to solving one of the world’s biggest problems – enabling affordable broadband Internet access for everyone,” Wyler said in a statement. “We are excited about the next phase, which will involve working with countries, telecom operators and aid organizations to help them realize their goals of open and ubiquitous access.”

Google confirmed in February a $900 million investment in SpaceX to support innovation in space transportation, reusability and satellite manufacturing.

Armed with fresh Google funding, SpaceX chief executive Elon Musk in January announced a plan to field a 4,000-satellite constellation in low Earth orbit for global Internet service, with initial operations expected within five years.

Musk said SpaceX will build its own satellites at a new manufacturing center in Redmond, Washington, keeping with the company’s penchant for in-house hardware production.

OneWeb possesses rights to Ku-band spectrum with the International Telecommunications Union required to provide broadband Internet services from low Earth orbit. Musk’s Internet venture has placed filings with the ITU, an agency responsible for ensuring no interference between space-based radio transmitters, but has not secured rights to a frequency for Internet service.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.