Ground crews plan to load the final cargo into SpaceX’s Dragon supply ship Saturday after the capsule’s Falcon 9 rocket booster briefly fired up on the launch pad at Cape Canaveral for a flight readiness check.

The Falcon 9 rocket ignited its nine Merlin 1D first stage engines at 4 p.m. EDT (2000 GMT) Friday as hold-down clamps kept the the 208-foot-tall booster firmly on the ground at Cape Canaveral’s Complex 40 launch pad.

The engines throttled up to full power, then shut down a few seconds later. The prelaunch engine firing — called a static fire by SpaceX — is the company’s last major test before clearing the rocket for final countdown preparations.

“I heard it was very successful — full-duration — and that clears the next coming days up to launch on Sunday morning,” said Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president of mission assurance and launch chief engineer.

Fresh food and time-sensitive experiments will go into the capsule Saturday.

Liftoff is timed for Sunday at 10:21:12 a.m. EDT (1421:12 GMT), approximately the moment the Earth’s rotation carries Cape Canaveral into the path of the International Space Station’s orbit.

“It’s a one-second launch window to catch the ISS in its plane and make sure that we are in the right orbit under it,” Koenigsmann said.

After flying northeast from Florida’s Space Coast, the Falcon 9’s second stage will deploy the logistics-laden Dragon spacecraft into orbit about 10 minutes later, beginning a two-day pursuit of the space station.

More than 4,000 pounds of provisions, experiments and spare parts will be packed inside the Dragon spacecraft for Sunday’s launch.

The materials include nearly 1.5 tons of care packages, food and provisions for the space station crew, a ton of spare parts and other items to maintain the orbiting research lab, and 1,166 pounds of hardware for science experiments.

Astronaut Scott Kelly and cosmonaut Gennady Padalka will monitor the Dragon capsule’s approach Tuesday and extend the space station’s 58-foot robot arm to grab the spacecraft as it floats 30 feet beneath the complex. The arm will maneuver the Dragon to a berthing port on the space station’s Harmony module, where the crew will open hatches and begin unloading the supplies inside.

The mission is the first cargo flight to the space station since a Russian Progress resupply and refueling freighter spun out of control minutes after liftoff in April. Russian ground controllers were unable to stabilize the unmanned supply ship, which re-entered the atmosphere in May, destroying its contents.

Mike Suffredini, NASA’s space station program manager, said technicians added extra food and clothes to the cargo complement for Sunday’s mission, which is called SpaceX-7, or CRS-7.

“Even with that (Progress) loss, we have very good logistics on-board for the entire crew,” Suffredini said Friday. “We’re good until the October timeframe if no other vehicles show up, and with SpaceX-7, we get ourselves pretty much to the end of the year with most of the supplies.”

After a remarkable streak of successful launches — with just one launch failure from 1998 to 2014 — two resupply flights to the complex went down in six months. An Antares rocket crashed moments after liftoff from Virginia on the “Orb-3” mission in October, followed by the Progress mishap in April.

According to Suffredini, space station officials kept a reserve of food, spare parts and other crucial items aboard the complex to keep operations going in case of a launch failure.

“You can see why we do that,” Suffredini said. “We’ve had really no impact to research at all given both the Orb-3 anomaly and this recent Progress anomaly… We expect occasionally that things won’t go quite right. In general, that can happen, so we try to protect ourselves for that.”

The cargo delivery will do more than restock the space station with essentials.

A new docking adapter to receive future commercial crew spaceships in development by SpaceX and Boeing is inside the Dragon spacecraft’s unpressurized trunk.

Two virtual reality headsets developed by Microsoft and NASA will go up to help the space station crew work on experiments and repair broken parts. The devices use Microsoft’s HoloLens holographic technology, allowing experts on the ground to see what an astronaut sees and draw annotations to help crew members through a task, according to NASA.

Part of a joint project between Microsoft and NASA named Sidekick, the space-rated HoloLens can also display animated holographic illustrations over objects to give astronauts instructions.

NASA says the test will help prepare for future deep space expeditions, where astronauts will need to be more independent of help from Earth.

Also aboard Dragon: Experiments to study combustion fuels in microgravity, observe meteors streaking through Earth’s atmosphere, monitor plant growth in special habitats on the space station, and track the human body’s response to spaceflight.

The Dragon spacecraft also carries small CubeSats to be deployed from the space station’s Japanese laboratory module.

The capsule is scheduled to leave the space station Aug. 5 for a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean with 1,400 pounds of research specimens and hardware requiring analysis and repairs.

The launch will kick off SpaceX’s seventh operational cargo delivery to the outpost since October 2012. Headquartered in Hawthorne, California, SpaceX has a contract worth approximately $2 billion for 15 resupply missions to the space station.

“It’s the seventh flight,” Koenigsmann told reporters Friday. “Dragon has been super reliable and so has Falcon 9. The primary mission on this one is obviously getting Dragon and its payload up into orbit, and then phase it into an orbit where it can dock with the space station.”

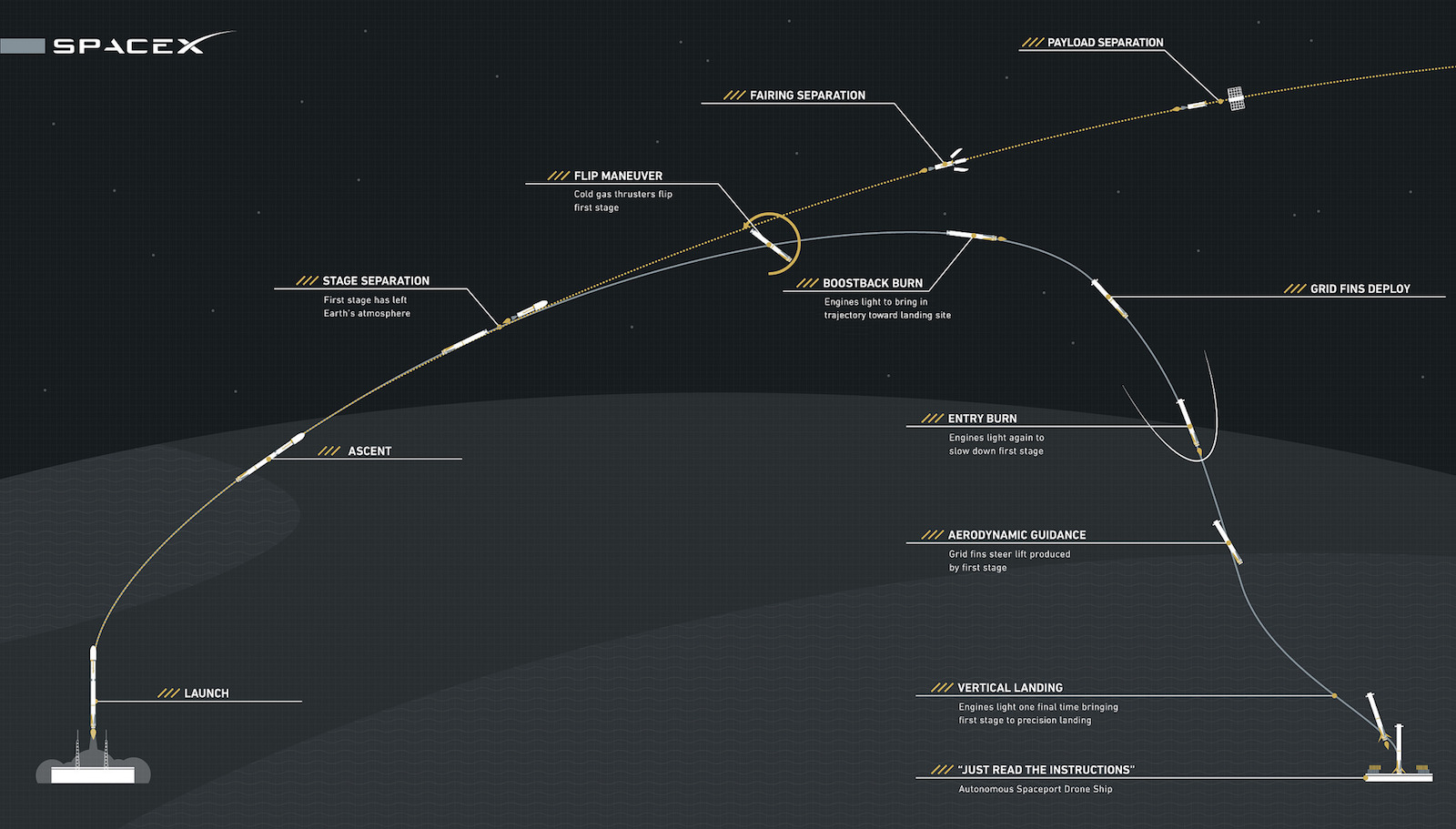

But outsiders — and many industry insiders — will pay much attention to the descent of the Falcon 9 booster stage to a targeted landing on a barge positioned in the Atlantic Ocean downrange from Cape Canaveral.

Sunday’s launch will be the third time SpaceX has tried to recover an intact first stage on the landing vessel. Previous attempts were thwarted when the rocket’s steering fins ran out of hydraulic fluid, and when an engine valve got stuck in the wrong position.

“You look at the data, you evaluate this, and then you make corrections,” Koenigsmann said. “That’s ultimately how you succeed, in my opinion, and make a safe landing in the end. The fact that we had two (landing attempts) so far gives me confidence that we had two problems that we solved.

“Until we’ve solved this problem end-to-end, there’s always going to be some uncertainty about the outcome, but I feel a little bit better (this time),” he said.

SpaceX says the rocket flyback demos will help make the Falcon 9 rocket partially reusable, an objective long sought by the company since its founding by high-tech mogul Elon Musk in 2002.

If the Falcon 9 first stage nails the landing, the SpaceX recovery team will bring the 14-story booster back to port in Jacksonville, Florida. It would eventually be trucked to SpaceX’s rocket development site in Central Texas for thorough inspections and tests before the company considers a second launch of the vehicle, Koenigsmann said.

“The vehicle is designed to fly multiple times — to be reusable — and we’re going to test that,” he said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.