A 2.9-ton rainfall research satellite fell into Earth’s atmosphere Tuesday for a destructive re-entry after a 17-year mission, according to NASA.

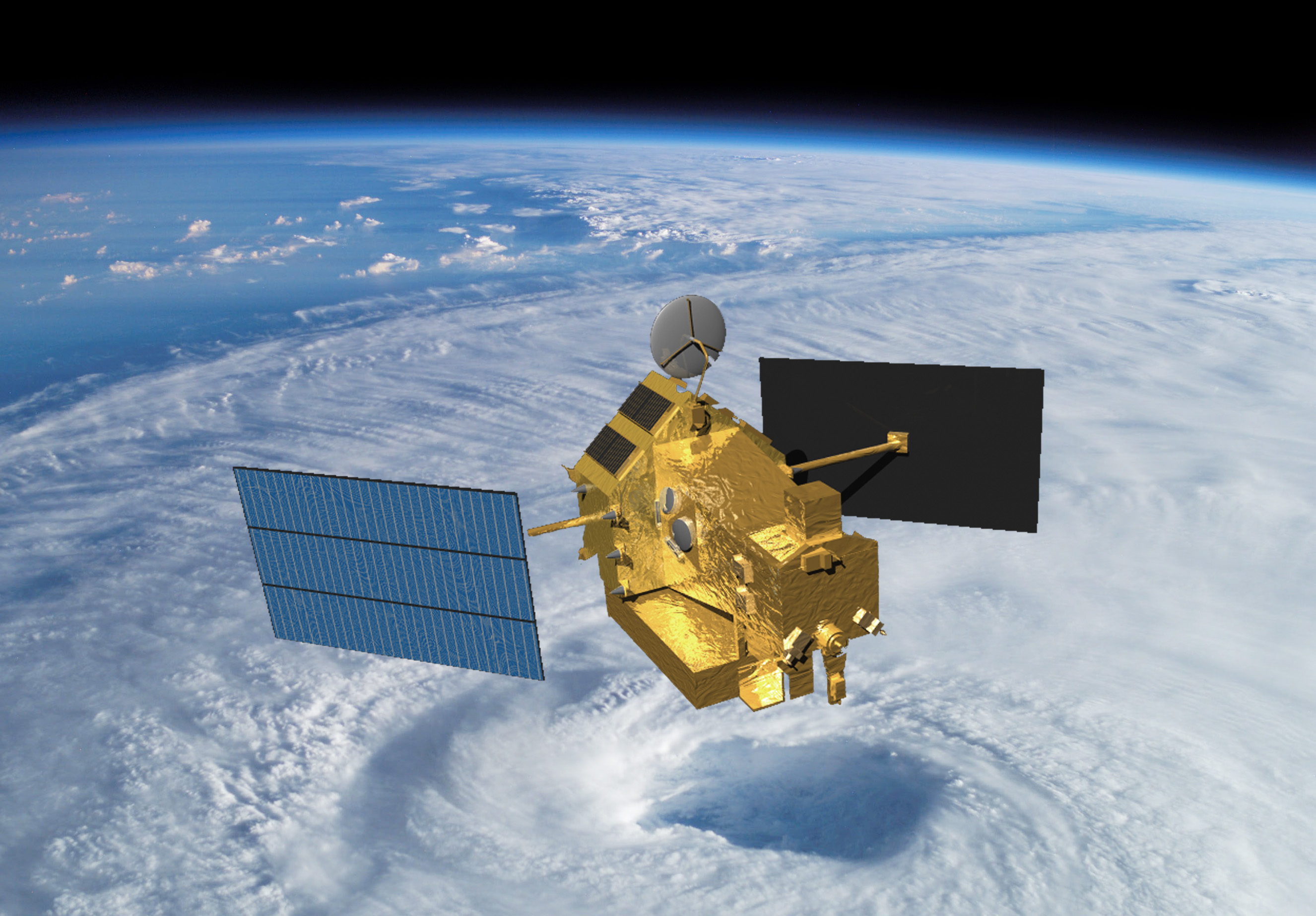

Out of fuel and destined for an uncontrolled re-entry, the U.S.-Japanese Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission, or TRMM, switched off its instruments in April as the spacecraft descended too low to collect usable science data.

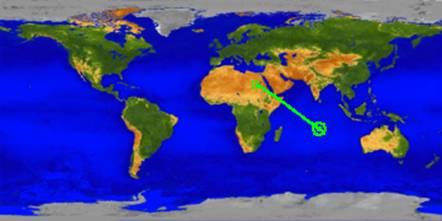

The TRMM satellite’s re-entry occurred at 0355 GMT Tuesday (11:55 p.m. EDT Monday) over the South Indian Ocean, according to U.S. Strategic Command’s Joint Functional Component Command for Space, which operates the military’s Joint Space Operations Center to track objects in orbit.

Most of the spacecraft was expected to burn up during re-entry, and NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office predicted 12 components of the TRMM satellite could survive the scorching fall through the atmosphere, including propellant and pressurant tanks, reaction wheel flywheels, solar array actuators, antenna brackets and several other pieces.

The fragments that could have reached Earth’s surface totaled 247 pounds, or about 4 percent of TRMM’s dry mass, experts said. None of the debris that potentially survived re-entry is toxic, but NASA cautioned some of the pieces could have sharp edges and said fragments from the satellite should be reported to local authorities in the unlikely event any components are recovered.

A risk assessment conducted by NASA showed a 1-in-4,200 chance debris from the falling satellite could harm someone, more than twice the 1-in-10,000 re-entry casualty risk limit set in U.S. government policy.

NASA officials decided to accept the extra risk by weighing the benefits of TRMM’s observations of tropical cyclones, measurements that may have led to life-saving improvements in hurricane forecasts.

TRMM was originally designed to carry reserve fuel to guide the satellite to a controlled re-entry over an uninhabited stretch of the South Pacific Ocean, but then-NASA Administrator Mike Griffin in 2005 decided to extend the mission and dip into the propellant set aside for a guided descent from orbit.

A recommendation from the National Research Council to forgo the re-entry and continue the mission prompted Griffin’s decision. NASA leaders and scientists concluded TRMM’s contributions to tropical cyclone forecasting outweighed the risks of an uncontrolled re-entry.

Assembled at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, TRMM launched Nov. 27, 1997, on an H-2 rocket from Tanegashima Space Center, Japan.

The $650 million mission was supposed to last three years, but TRMM received multiple extensions and kept monitoring cyclones, monsoons and other tropical weather systems until April.

TRMM hosted a Japanese-built precipitation radar –the first of its kind ever flown in space — that provided 3D views inside tropical cyclones and storms in a belt near the equator. TRMM data helped forecasters at the National Hurricane Center predict tropical storm intensification.

NASA and JAXA launched a follow-on observatory last year named the Global Precipitation Measurement mission. The GPM satellite flies in a different orbit than TRMM, covering a wider swath of Earth from the tropics nearly to the poles to expand precipitation research to include winter weather.

The new mission’s upgraded instruments also detect lighter precipitation than TRMM, feeding data into long-range climate models and short-term weather forecasts.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.