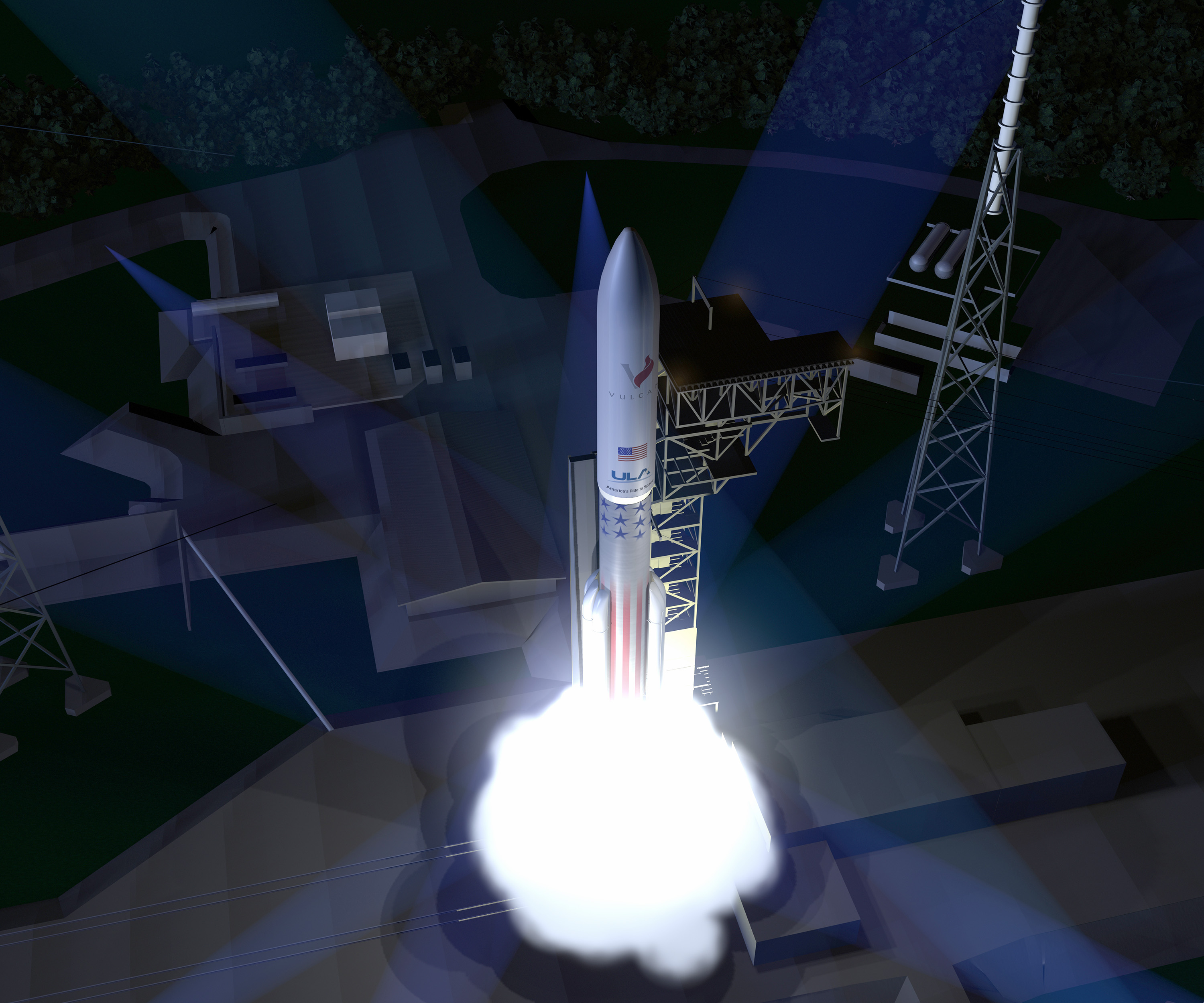

United Launch Alliance will need to lure commercial customers to ensure the economic viability of its new Vulcan rocket, which is set to debut in 2019 just as the rate of U.S. military satellite launches is due to take a dip.

The Vulcan rocket must fly at least 10 times per year to keep factory and launch crews operating at the efficiencies needed to reach ULA’s price goal of $100 million per mission, according to Tory Bruno, ULA’s president and chief executive.

ULA says the Vulcan rocket can be ready for its debut launch in 2019, and the company plans to introduce the new launcher over several years while still flying the Atlas 5 and Delta 4 boosters in ULA’s existing inventory.

The Vulcan may not be certified to send up the most expensive national security payloads until 2023, so ULA plans to rely on commercial business for the new rocket’s early launches.

ULA unveiled some details of the Vulcan rocket design April 13 in response to competitive pressures from rival SpaceX, which says it can launch military satellites at lower prices than ULA. The Atlas 5 rocket’s Russian RD-180 main engine also thrust ULA under scrutiny after Russian officials threatened last year to block exports of rocket parts to the United States as relations between Washington and Moscow strained in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Russia never followed up on the threat, but it was enough to get ULA and the federal government to move away from the RD-180 engine and toward a U.S.-made replacement. ULA’s commercially-developed Vulcan rocket booster stage will be powered by two methane-fueled BE-4 engines built by Blue Origin or a pair of kerosene-burning AR-1 engines supplied by Aerojet Rocketdyne.

SpaceX expects to win approval from the U.S. Air Force to win national security launch contracts by June, and the arrival of the Falcon rocket family to the military launch market — plus the inaugural flight of ULA’s Vulcan rocket — is forecast to come just as demand for military satellite launches takes a nosedive.

“The national security market actually has a big dip in in the 2018-2022 kind of timeframe,” Bruno said in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “The good news is there are new entrants and there’s competition. Competition is a sign that the industry is becoming more accessible and more mature, so that’s all good news. The ironic side of that is it’s happening just as the demand from the government in terms of national security space is actually falling off.”

By the end of the decade — and if schedules hold — the Air Force’s new fleet of nuclear-hardened Advanced Extremely High Frequency communications satellites will have been deployed in orbit, along with the Navy’s constellation of new MUOS relay stations designed to connect mobile users around the world.

Up to 10 satellites will have been launched into the Air Force’s Wideband Global SATCOM satellite system, and the military’s new-generation network of SBIRS missile warning satellites will be near completion.

That leaves replenishment of the Air Force’s GPS navigation fleet and launches of classified National Reconnaissance Office spy satellites as the major sources of military launch activity.

“Whereas today, and in past years, the Air Force alone flew about 10 (missions) a year, the Air Force and NRO are going to drop to more like five a year in the (2018-2022) window that I described,” Bruno said. “On the other side of the window, it picks back up again. It comes all the way back and then some. In that middle timeframe, there is a decline and it will be split between multiple providers now that we have them and have competition.”

The Pentagon is legally required to ensure its satellites have redundant means to launch into orbit, a risk mitigation measure crafted to keep missions flying even if one rocket is grounded.

The Atlas 5, Delta 4 and Falcon 9 all have near-flawless flight records to date.

Boeing and Lockheed Martin developed the Delta 4 and Atlas 5 rocket fleets to answer the military’s requirement, and the companies merged their launcher divisions to form ULA in 2006.

With the Falcon 9 about to give the Pentagon another launch option, ULA plans to retire the basic single-core version of the Delta 4 rocket in 2019 because the company says it is too expensive to compete with the Falcon 9 rocket built by SpaceX, which officials expect to be certified by the Air Force to win national security launch contracts by June.

ULA says the Atlas 5 rocket — while still more expensive than SpaceX’s launcher — could compete with SpaceX for military satellite launches because it is cheaper than the Delta 4 and can lift heavier spacecraft into orbit than the Falcon 9.

Bruno says the Atlas 5, Falcon 9 and the triple-core heavy-lift version of the Delta 4, which ULA plans to keep operational into the early 2020s, can handle all of the military’s launch requirements after 2019 until the Vulcan is certified.

But there is a wrinkle in ULA’s strategy.

Legislation passed by Congress last year forbids the Pentagon from launching national security satellites with rockets powered by Russian engines beyond ULA’s RD-180 procurement agreements already in place.

ULA and Air Force officials have argued for the restriction on Russian engines to be relaxed, fearing the law would leave the Pentagon hamstrung in its launcher procurements.

SpaceX is developing its own bulked-up launcher called the Falcon Heavy, which is scheduled to launch from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida for the first time later this year. SpaceX has signaled its intent to work with the Air Force to certify the Falcon Heavy, giving the California-based space transportation firm access to a larger slice of the launch market than reachable with the smaller Falcon 9.

The Air Force and SpaceX have not disclosed a timetable for Falcon Heavy’s certification, but Shotwell said in March the process should go quicker than the two-year review needed for the military to sign off on the Falcon 9.

The Falcon Heavy’s certification plan calls for the rocket to complete three successful launches, including two consecutive successful flights, before getting clearance for national security satellite launches, according to a report published by Space News.

The dearth of national security payloads, the availability of new launchers, and the Vulcan’s lack of Air Force certification will compel ULA to find other customers for the new rocket, at least at first.

“We are definitely going to be filling back in with civil missions for NASA,” Bruno said. “We already do NASA’s most challenging science missions like New Horizons and Solar Probe Plus, but also commercial crew and commercial cargo, where we have entered those two markets and are providing flights over the next coming years.

“And we will be doing commercial which is primarily commercial telecommunications and some commercial Earth observation as well,” Bruno said.

The Atlas 5 rocket’s high price and busy manifest means it only occasionally launches with commercial payloads, with most of the international contracts in recent years going to SpaceX or Arianespace.

ULA boss Bruno says the first step to return to the commercial marketplace is being competitive on price, not a strong point for Atlas and Delta rockets in recent years.

“First, you’ve got to have that competitive price offering — that $100 million mark, if you will,” Bruno said. “But we’re also going to be introducing some innovations in the way people can come to us to purchase the launch services and the amount of time they have to set back from that launch.

“Even in the commercial industry, people are ordering their launch services a couple of years out,” Bruno said. “That’s a challenge for commercial telecom providers.”

The wait for a launch slot can be a revenue loser for a commercial communications company, which must coordinate the procurement of a launcher and spacecraft platform to be ready at the same time, all while selling transponder capacity on the satellite to end users.

“What I want to do is shorten that span,” Bruno said. “I want to make it more affordable. I want make it much easier for them to purchase it and to do the trades that they have to do, and then I want to shorten the spans so they don’t have to order things quite so long in advance. All of that will help us be competitive in the commercial market and then also be available to all the other customers as well.”

ULA says the lower-end model of the Atlas 5 rocket sells for about $164 million, and a heavy-duty model of the Delta 4 rocket goes for nearly $400 million. Bruno’s goal is to offer a barebones Vulcan rocket for as little as half of today’s price for a basic Atlas 5 rocket. ULA could add up to six strap-on boosters to send up heavier satellites at a higher price.

The Vulcan will eventually be able to dispatch all classes of spacecraft, according to ULA.

SpaceX advertises the Falcon 9 rocket for $61 million on its website. The larger Falcon Heavy booster in development is listed at $90 million for missions lofting up to 6.4 metric tons (14,100 pounds) into geostationary transfer orbit, the drop-off point for most communications satellites.

SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell told lawmakers in March that those prices would go up to $80 million to $90 million for an Air Force launch on a Falcon 9 rocket due to extra requirements levied by the military. Falcon Heavy launch may cost the Air Force up to $160 million when carrying a national security payload, she said.

The prices assume the Falcon and Vulcan rockets remain expendable.

SpaceX has unsuccessfully tried to recover its Falcon 9 first stage boosters on a landing platform at sea, but the company is optimistic it can debug the rocket and achieve a smooth touchdown on one of its upcoming launches.

ULA wants to capture the Vulcan rocket’s discarded main engines with a parachute and helicopter, but Bruno said the reuse innovation would not be tested until the 2020s.

Another key player in the commercial launch market beginning in 2020 will be Arianespace’s new Ariane 6 rocket. Its designers say the larger of its the Ariane 6’s two configurations — comparable to a mid-range Vulcan and more capable than a Falcon 9 — will sell for 90 million euros, or about $96 million at current exchange rates.

Stephane Israel, Arianespace’s chairman and CEO, said in a December interview that the new Ariane 6 rocket will need to fly 11 times per year to financially break even. The European Space Agency has guaranteed that European governments will purchase at least five Ariane 6 launches per year, leaving the rest of the manifest to be filled with commercial flights.

SpaceX officials have not publicly disclosed their breakeven numbers.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.