Back on Earth after a whirlwind journey 20,000 miles around the world, an experimental re-entry demonstrator is on the way to Europe for post-flight inspections aimed at gathering design inputs for future reusable space vehicles.

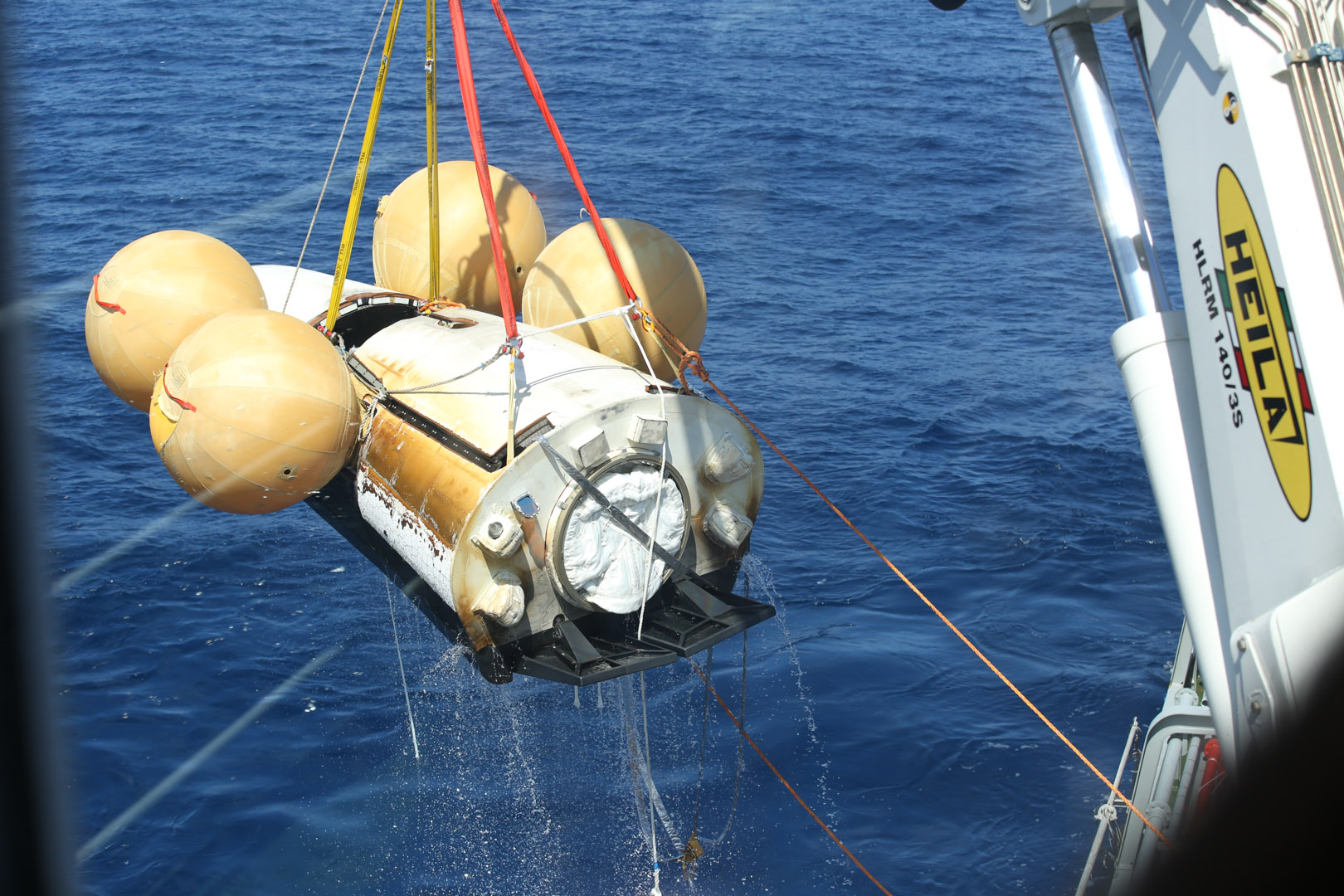

The spacecraft splashed down in the equatorial Pacific Ocean west of the Galapagos Islands after a 100-minute test flight Wednesday. Four airbags inflated to keep the space plane from sinking as divers deployed from an Italian recovery vessel in Zodiac boats speeding toward the splashdown site.

A few hours later, a crane on the Nos Aries ship lifted the 16-foot-long (5-meter) Intermediate Experimental Vehicle from the ocean and placed it on the vessel’s deck.

The IXV launched from the European-run spaceport in French Guiana aboard a Vega rocket at 1340 GMT (8:40 a.m. EST) and reached a maximum altitude of 256 miles (413 kilometers) before descending back into Earth’s atmosphere at nearly 16,800 mph (7.5 kilometers per second), using four rear-mounted rocket thrusters and two maneuvering flaps to steer toward its target landing zone.

Officials said the craft had a nearly on-target splashdown after using aerodynamic resistance, S-turn banking maneuvers and a series of parachutes to slow from hypersonic speed to a gentle landing velocity of about 15 mph (7 meters per second).

Technicians clad in protective hazardous material suits from the European Space Agency and Thales Alenia Space, which built the IXV re-entry demonstrator, planned to decontaminate the spacecraft’s hydrazine fuel tank after the recovery operation.

The Nos Aries is sailing back to port in Genoa, Italy, where it is due to arrive in March. The IXV will be transported from Genoa to an ESA test center in the Netherlands, where engineers will disassemble the spacecraft and see how it weathered the brief test flight.

The ship will traverse the Panama Canal, where it will drop off most of the recovery team to fly back to Europe.

Before it splashed down, the IXV radioed recorded data from more than 300 sensors on the spacecraft to an antenna on the Nos Aries ship. With the successful recovery of the spacecraft, engineers can physically examine its condition.

“From Genoa, the IXV will be transported to the ESTEC site in Holland at Noordwijk, where it will be stored,” said Roberto Provera, director of human spaceflight and transportation programs at Thales Alenia Space. “Before storage, we will analyze all the results. We will have the data recorded on-board, and we will have to analyze the materials on the vehicle to have a first look at the various components to see how they reacted to the flight.”

Giorgio Tumino, ESA’s IXV program manager, said in an interview before the flight that one of the objectives is to evaluate the reusability of critical parts of the spacecraft.

“One of the mission objectives, which is an important one, is to assess the reusability of the avionics, the structural components, and so on,” Tumino said. “We want to monitor the environment inside and outside.”

The IXV — a lifting body design — was expected to encounter temperatures near 3,100 degrees Fahrenheit (about 1,700 degrees Celsius) during the hottest part of re-entry. The craft’s nose and flaps saw the most extreme temperatures.

“The IXV landing — the advantage of this is that we had a far more accurate re-entry than we had with a capsule, and it also means that we’re moving a step toward the reutilization of re-entry bodies,” said Jean-Jacques Dordain, ESA’s director general. “That is something that’s vital for the future of space activities.”

The IXV program’s budget was 150 million euros — around $170 million. The cost of the Vega launcher — around 40 million euros ($45 million) — is counted separately. Italy led the development of both the IXV and the Vega programs.

The initial results from Wednesday’s test flight will be announced in the second quarter of this year, officials said.

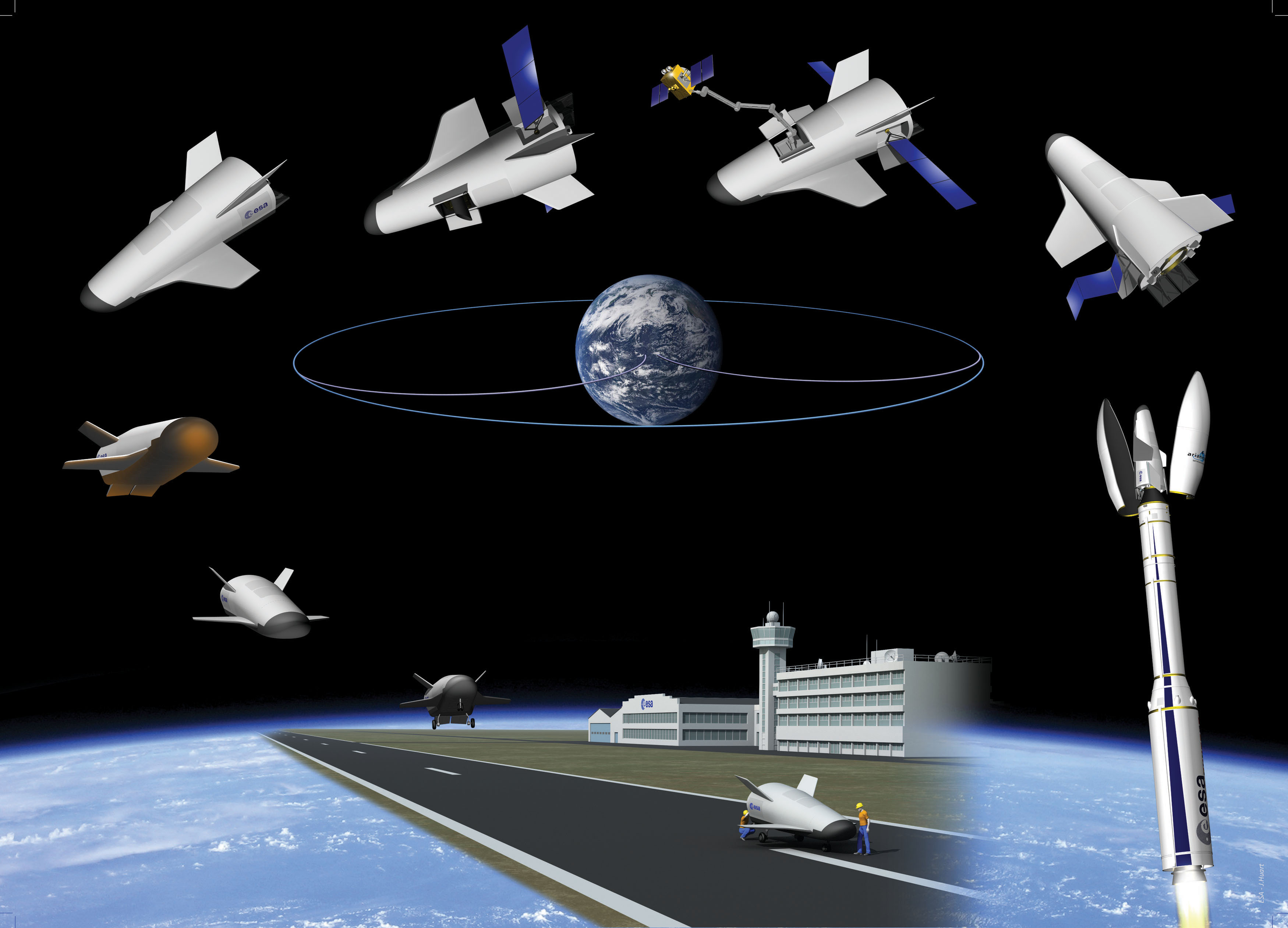

Lessons learned from the IXV test flight will feed into the design of a future European space plane.

ESA member states approved limited funding for the Program for Reusable In-orbit Demonstrator for Europe, or PRIDE, at a ministerial-level meeting in December.

The budget supports design studies and early definition of the PRIDE space plane, which is envisioned to roughly the same size and shape as the IXV testbed flown Wednesday. It will also blast off on Europe’s Vega rocket, but the future craft will enter Earth orbit, perform a mission, then return to Earth for landing on a runway.

But the program needs a boost in funding in coming years to keep to a schedule for a first flight by 2020.

“Re-entry form low Earth orbit is key for a lot of applications in space transportation, from cargo to crew transportation, to servicing the space station, to Earth observation, to have quick access to orbit and quick retrieval for satellite servicing,” Provera said. “We dream of a space plane in the future. It will take some time to develop, but I think with this flight we could make a break on this path.

“PRIDE will be the second step,” Provera said. “I think there are many other technologies to prove before going for an operational system, like with orbital maneuver capabilities, precise landing, and so on … Hopefully, we will have it flying in three or four years, so the lessons learned from IXV will not be lost.”

The IXV flight could also help engineers working on concepts for reusable launcher stages that fly back back to Earth after completing their missions.

The lifting body’s maneuvering systems — thrusters and flaps — are derived from technologies used on Europe’s Ariane 5 and Vega launchers.

“We have built a lot on our launcher technology,” Tumino said. “t was very important because we could also use the mission to create reusable launcher technology, and the thruster is one of these technologies.

“The flaps are the second thing we have inherited from our launcher technologies,” Tumino said. “These are electromechanical actuators, the same actuators used on Vega for the thrust vector control to steer the nozzle. We had to do some modification, but its basically 80 to 90 percent the same technology.”

The IXV is blanketed in black ceramic thermal protection panels bolted to the IXV’s belly, and cork-based and silicon-based light-colored materials on the spacecraft’s top and sides.

“If you need to return to the ground, you need all of what we are doing with IXV,” Tumino said. “I’m talking about in Europe — the U.S. has had this basic know-how for years … Re-entry vehicles and launchers operate in air, so they use similiar disciplines. For example, aerodynamics and aerothermal dynamics in launchers and re-entry systems is the same, thermal protection is a common problem, and guidance navigation and control is a common problem, which is different from satellites orbiting in space having nothing to do with the atmosphere.”

Europe’s next-generation launcher — the Ariane 6 — is an expendable rocket. But two ESA member states — France and Germany — are working on future launcher concepts that could be reusable.

“The IXV return demonstration is a fundamental element on any future activity that Europe might undertake to bring back launcher stages to the ground,” Tumino said. “Whether this is a first stage or an upper stage, we will see because the discussion is just starting. Even for a lower stage, there is an extreme need to have thermal protection.”

European space officials are often asked about their reusable rocket plans after SpaceX — the U.S. launch company founded by Elon Musk — began experimenting with unprecedented flyback maneuvers in a bid to land a booster stage at sea.

SpaceX’s efforts are widely viewed to be responsible for renewed talks of the benefits — and, as many competitors often point out, the treacherous economics — of a reusable launcher.

Musk has argued that recycling rocket stages only makes sense if the reuse is “rapid and complete,” offering a vision for launchers that can be landed, refueled and flown again.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.