A spherical U.S. Navy spacecraft the size of a beach ball spring-ejected from a new satellite deployer outside the International Space Station last week, debuting a fresh way for low-budget space missions to reach orbit.

The satellite — named SpinSat and developed by the Naval Research Laboratory — will test out new electrically-controlled micro-thrusters, help refine the military’s ability to track objects in space, and acquire data on the density of the tenuous upper layers of Earth’s atmosphere.

SpinSat’s deployment from the space station Friday was the first time a satellite was released from a new mechanism designed to accommodate spacecraft weighing up to 100 kilograms, or about 220 pounds.

The space station already has a deployer for tiny CubeSat satellites, which weigh less than 10 pounds.

The debut of a new deployer known as the Space Station Integrated Kinetic Launcher for Orbital Payload Systems (SSIKLOPS) allows the complex to serve as a launch platform for larger, more capable satellites.

The deployer is nicknamed Cyclops and measures about the size of a living room coffee table. NASA partnered with the U.S. Air Force’s Space Test Program to develop the system, which launched with the SpinSat spacecraft on a SpaceX Dragon supply ship in September.

Officials say the Cyclops deployer will offer small satellite owners a cost-effective — and safer — way to launch their spacecraft into orbit. Spacecraft intended for deployment from the space station could blast off comfortably packed inside the pressurized cabin of one of the research lab’s cargo vehicles, then astronauts would unpack the satellite, attach it to the deployer inside the station, then use an airlock to send the apparatus outside into the vacuum of space.

But using the space station as a launching point puts strict limits on a satellite’s operating orbit.

The outpost circles Earth at an altitude of about 260 miles, and its orbit is tilted at an angle of 51.6 degrees to the equator. Engineers say a satellite released from the space station is likely to re-enter the atmosphere and burn up within several months to a couple of years unless it carries rocket thrusters to maintain its orbit.

Friday’s deployment of SpinSat provided a “proof of concept” exercise to demonstrate how the Cyclops system works.

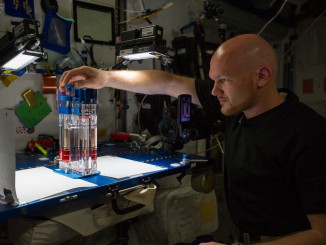

Astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Terry Virts attached SpinSat to the deployer, slid the device through an airlock and positioned the device outside the space station’s Japanese Kibo laboratory module.

A Japanese robotic arm grabbed the deployer and moved it to the correct location for SpinSat’s release.

We deployed a satellite today! Here's SPINSAT leaving the airlock pic.twitter.com/BCfZagKvnN

— Terry W. Virts (@AstroTerry) November 28, 2014

The 22-inch-diameter, 126-pound SpinSat spacecraft carries 72 tiny solid-fueled rocket thrusters. Engineers hope to test the the rocket jets and adjust their thrust levels by fluctuating the electrical current reaching the thrusters.

The thrusters could be used to control the spin or orientation of future small satellites.

Officials plan to track SpinSat’s orbit and spin rate using lasers. The satellite is covered in reflectors to bounce laser light beams back to receivers on the ground, helping engineers determine which way the spacecraft is pointing.

The next satellite planned to deploy from the space station’s Cyclops system is Lonestar 2, a tandem spacecraft from the University of Texas and Texas A&M University scheduled for liftoff early next year.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.