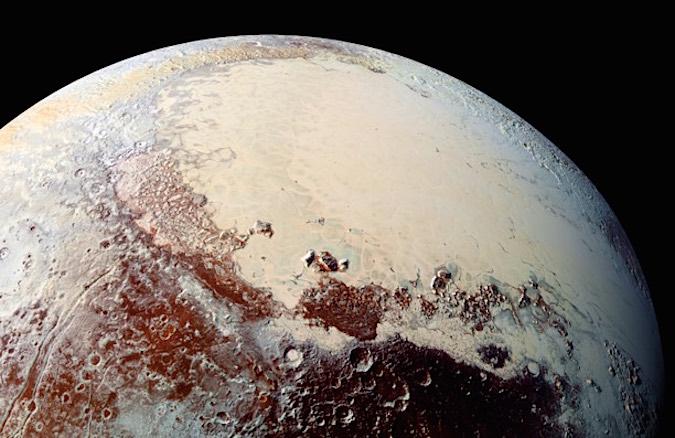

Scientists believe they can explain how an ocean of water is lurking beneath an ice sheet inside Pluto’s prominent heart-shaped region, an iconic frozen landscape discovered during the New Horizons spacecraft’s flyby last year.

A slushy buried sea under the icy plains of Sputnik Planitia would help counterbalance the gravitational weight of the dwarf planet’s largest moon Charon, which stays fixed above the opposite side of Pluto, researchers reported last week in the journal Nature.

Fed by computer model results and observations from New Horizons, the studies also present evidence that Pluto rolled over in the aftermath of a cataclysmic collision with a comet or another icy object that carved out the basin that became Sputnik Planitia, a 600-mile-wide (1,000-kilometer) feature that forms the left half of Pluto’s bright heart.

It turns out a mass of ice that filled Sputnik Planitia could have pulled Pluto off balance, re-orienting the dwarf planet to have the subsurface ocean facing almost perfectly away from Charon.

“The New Horizons data say it’s not only opposite Charon, but it’s really close to being almost exactly opposite,” said Richard Binzel, a co-investigator on the New Horizons mission from MIT. “So we asked, what’s the chance of that randomly happening? And it’s less than 5 percent that it would be so perfectly opposite. And then the question becomes, what was it that caused this alignment?”

It may be counterintuitive to think of Sputnik Planitia, a low-elevation plain surrounded by craggy mountain ranges, as a bulging bulk of mass capable of balancing the strong tidal tug from Charon.

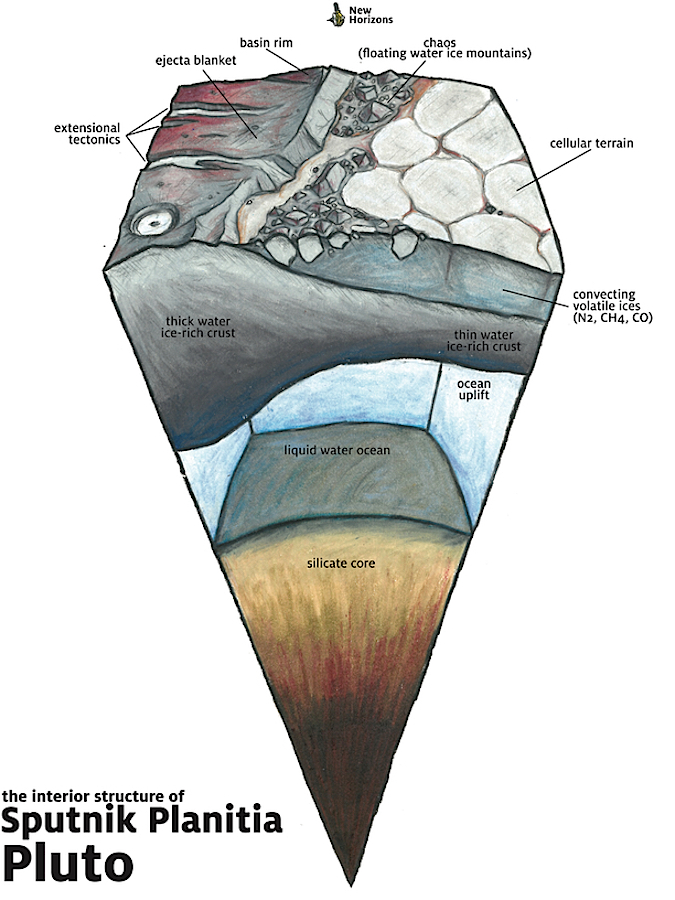

“It’s a big, elliptical hole in the ground, so the extra weight must be hiding somewhere beneath the surface. And an ocean is a natural way to get that,” said Francis Nimmo, professor of Earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Nimmo was the lead author of a paper published Nov. 16 in Nature describing the new findings.

The impact that formed Sputnik Planitia triggered an upwelling of water that pushed up against a weakened top layer of icy crust, Nimmo writes.

“At that point, there is no extra mass at Sputnik Planitia,” Nimmo said in a press release from UC Santa Cruz. “What happens then is the ice shell gets cold and strong, and the basin fills with nitrogen ice. That nitrogen represents the excess mass.”

Pluto takes 248 Earth years to complete one trip around the sun in its distant, oblong orbit. That makes the dwarf planet’s seasons last more than a half-century, and because Pluto spins on its side, its poles experience decades of direct sunlight and complete darkness each orbit, creating dramatic temperature extremes.

Pluto’s equatorial regions, including Sputnik Planitia, have more consistent temperatures, as low as minus 400 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 240 degrees Celsius, cold enough to freeze nitrogen.

As the seasons change on Pluto, nitrogen frozen on the surface heats up to become vapor, then travels through Pluto’s tenuous atmosphere and falls as snow on Sputnik Planitia, adding more mass to the region.

“Each time Pluto goes around the sun, a bit of nitrogen accumulates in the heart,” said James Keane, a doctoral student at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory who wrote a separate paper published in Nature last week outlining how Pluto rolled into its current orientation after the creation of Sputnik Planitia.

“Once enough ice has piled up, maybe a hundred meters (330 feet) thick, it starts to overwhelm the planet’s shape, which dictates the planet’s orientation,” Keane said in a story posted on the University of Arizona’s website. “And if you have an excess of mass in one spot on the planet, it wants to go to the equator. Eventually, over millions of years, it will drag the whole planet over.”

The fresh deposits of nitrogen snow and convective heat from the deep interior create fissures and cracks — fault lines — in the ice in Pluto’s heart.

Scientists lean toward the presence of an underground ocean to fully account for the mass clumped at Sputnik Planitia. Without an ocean there, the mass needed to align Sputnik Planitia with the location of Charon would require an “implausibly thick” layer of nitrogen ice more than 25 miles (40 kilometers) thick, Nimmo wrote in Nature.

“We tried to think of other ways to get a positive gravity anomaly, and none of them look as likely as a subsurface ocean,” Nimmo said.

So what is Pluto’s hypothesized ocean like?

“Pluto is small enough that it’s just about almost cooled off but still has a little heat, and it’s about 2 percent the heat budget of the Earth, in terms of how much energy is coming out,” Binzel said in a story posted on MIT’s website. “So we calculated Pluto’s size with its interior heat flow, and found that underneath Sputnik Planitia, at those temperatures and pressures, you could have a zone of water-ice that could be at least viscous. It’s not a liquid, flowing ocean, but maybe slushy. And we found this explanation was the only way to put the puzzle together that seems to make any sense.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.