U.S. military radars have little trouble tracking the flux of CubeSats filling orbital traffic lanes, diminishing worries that new commercial CubeSat constellations could generate collision hazards in space, according to a report issued by NASA last week.

But 46 of the 231 CubeSats successfully launched from 2000 through the end of 2014 — about one in five — will remain in orbit more than a quarter-century. Space debris experts and most big international satellite operators have agreed to re-position spacecraft in low Earth orbit at low enough altitudes to naturally re-enter the atmosphere within 25 years at the end of their lives.

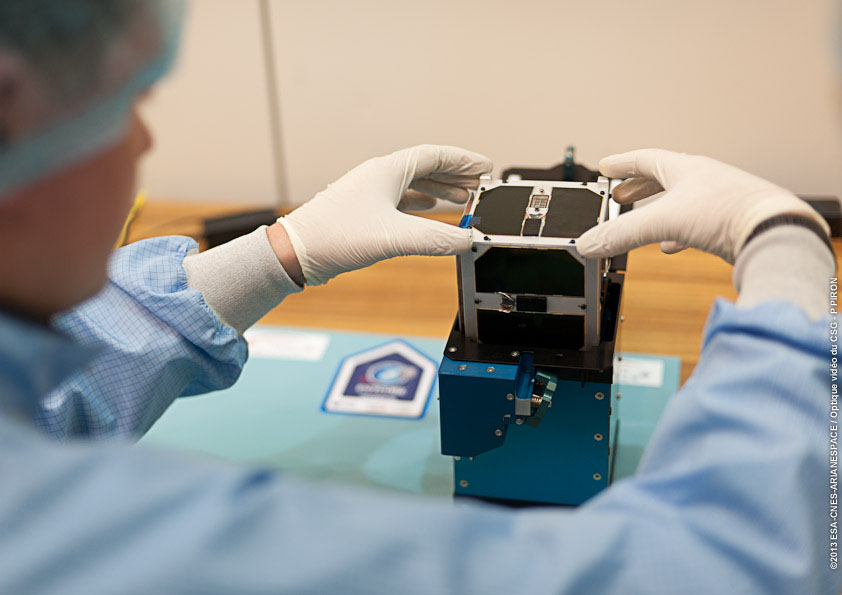

Most CubeSats range between the size of a Rubik’s cube and a shoebox, and all of the small satellites based on the CubeSat design have been tracked and catalogued by the U.S. military’s Joint Space Operations Center, according to a report issued July 22 by NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office.

Launches of large clusters of CubeSats in recent years, along with industry plans to deploy hundreds more, have raised concerns about the tiny satellites contributing to the orbital debris problem in low Earth orbit.

U.S. Air Force officials say the military tracks approximately 23,000 objects in space, most of which are derelict rocket stages, decommissioned spacecraft, or smaller fragments. CubeSats are a small fraction of the objects orbiting Earth, but unlike older pieces of space junk, the pace of deployment of future CubeSats is expected to increase.

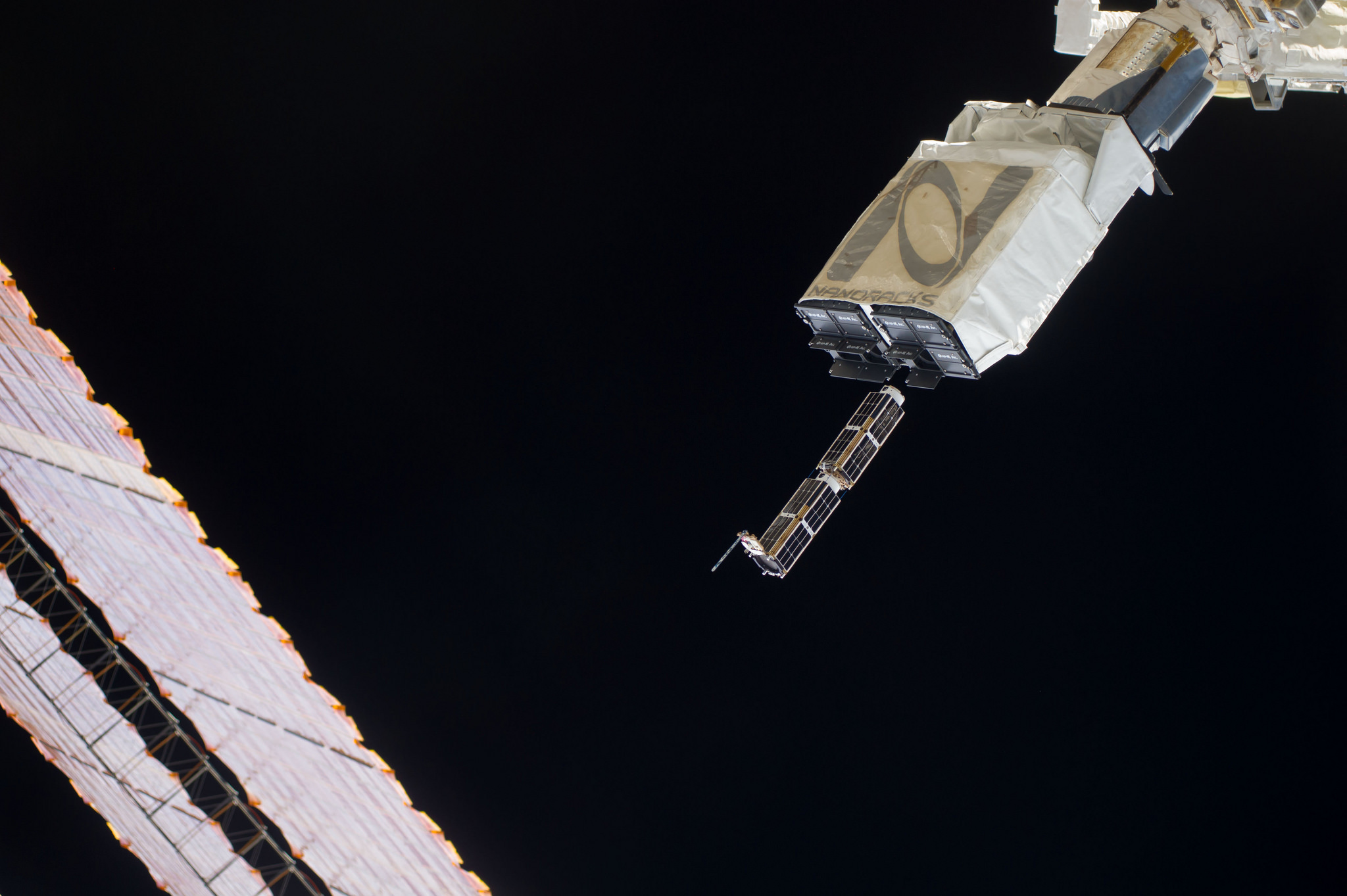

CubeSats launched inside pressurized cargo vessels and released outside the International Space Station are of little concern to space debris experts. The space station orbits at an altitude of about 260 miles, or 420 kilometers, where aerodynamic drag from the outer wisps of Earth’s atmosphere often brings CubeSats down within months.

For CubeSats sent to higher altitudes, the orbital lifetime is much longer, and most are not equipped with rocket thrusters to move out of the way of other satellites or lower their orbits at end-of-life.

The altitude cutoff for a 25-year lifetime is between 600 and 700 kilometers (373 to 435 miles), according to NASA’s orbital debris report.

“At higher altitudes, all CubeSats display longer on-orbit lifetimes and non-compliant residence times,” NASA officials wrote. “Lower altitude deployments, such as those from the ISS, are projected to be compliant.”

CubeSat operators who may prefer low-altitude orbits often find themselves at the mercy of larger satellite owners, such as government agencies. That is because nearly all CubeSats ride into space aboard powerful rockets as secondary passengers, meaning they must go to the same orbital destination as the primary payload.

In some cases, the only option for a CubeSat owner is to launch into a higher orbit outside the bounds of the 25-year lifetime rule.

Several companies are developing so-called “nano-launchers” designed to carry up small satellites on dedicated flights, sending them into whatever orbit they desire, but none of the lightweight boosters are flying yet.

One company operating a large fleet of CubeSats in low Earth orbit is Planet Labs, a San Francisco-based firm using the diminutive spacecraft to takes pictures of Earth from space.

Planet Labs now has more than 30 active satellites in orbit, with plans for a fleet of 125 CubeSat-based spacecraft in the next few years, enough to map the planet at least once every day.

“The community’s comfort with (CubeSats populating low Earth orbit) has been growing, I think,” said Chris Boshuizen, Planet Labs’ co-founder and chief technology officer. “We obviously need to set very firm codes of conduct to ensure that the commons of space is respected, and everyone is a responsible actor. Here at Planets Labs, we realize that being the first to do this, we have to set the best example of what best practices are, and we don’t want to be the company to mess it up for everybody.”

Planet Labs sends up most of its existing CubeSats to the space station aboard commercial resupply ships.

“We have very strict debris mitigation policies,” Boshuizen said in an interview with Spaceflight Now in June. “Our principal response to that is to launch into very low orbits that self-clean, which is why we use the ISS for a lot of our demonstrations.”

Boshuizen said Planet Labs sends its own satellite navigation data generated aboard the company’s spacecraft to the U.S. military and other satellite operators.

“I think this free sharing of information creates a culture that says it is OK to share, and that the needs of the community to know where everything is outweigh the needs for privacy,” Boshuizen said last month.

When Planet Labs engineers believe they settled on a suitable design for a full-up Earth-imaging constellation — they are rapidly finishing new CubeSat iterations every few months — the company will turn toward launching more of its satellites into sun-synchronous orbits, a type of orbit more suitable for Earth observation than the space station.

“Ideally, we want to launch our operational fleet into a very low sun-synchronous orbit, around 450 to 500 kilometers (280 to 310 miles),” Boshuizen said. “At 650 kilometers (404 miles), you’re compliant with the 25-to-30 year de-orbit rule. From 700 kilometers (435 miles) and up, you’re not compliant anymore, so we certainly would never launch any higher than that.”

Planet Labs has another reason for wanting to go lower: Its satellites get sharper views of Earth from lower orbits.

“At 500 kilometers (310 miles), you’re more like 4-to-7 years until de-orbit, so that’s our way of playing it very safe,” Boshuizen said. “Of course, resolution is linearly proportional with altitude, so the images are 30 percent sharper at 500 kilometers than 650 kilometers.”

Another Bay Area startup named Spire plans to field more than 100 CubeSats in orbits between 500 and 700 kilometers by 2017 to gather data on atmospheric temperature, pressures and humidity by monitoring radio signals from GPS navigation satellites.

Spire’s commercial weather satellite fleet will also track maritime traffic from orbit. It is hoping to sell data to companies and governments around the world.

Spire says it will minimize the impact of its satellites on the orbital debris environment through selecting safe orbits and designing CubeSats with short lifetimes.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.