STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

Four veteran astronauts have been selected to train for launch aboard new commercial crew capsules being built by Boeing and SpaceX that are intended to ferry astronauts to and from the International Space Station starting in 2017, NASA announced Thursday.

Station veteran Sunita Williams, along with shuttle veterans Robert Behnken, Eric Boe and Douglas Hurley, will work with both companies as they develop the new ferry ships and will be candidates for initial test flights.

“It’s really been the dream of all of us to participate in the test of a new vehicle, and a vehicle like a spacecraft is probably the gem, if you will, of a career,” Behnken said. “I would have been embarrassed as a test pilot school graduate to not have jumped at the opportunity, if it was offered to me, to fly a new spacecraft. Hopefully, I’ll get that chance soon.”

Said Hurley: “To be part of a new test program … is extremely exciting. The challenge from a test pilot perspective is great, and I’m just looking forward to (getting) from today all the way up to the space station.”

Boeing holds a $4.2 billion NASA contract to develop its CST-100 capsule, a spacecraft designed to carry at least four astronauts. The CST-100 will be launched atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket.

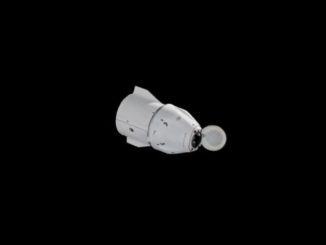

SpaceX holds a $2.6 billion contract to build a human-rated version of the Dragon capsule currently used to carry cargo to the space station. Like the CST-100, the piloted version of the Dragon will carry a crew of at least four but will fly atop the company’s Falcon 9 rocket.

The contracts call for at least one piloted test flight with at least one NASA astronaut on board “to verify the fully-integrated rocket and spacecraft system can launch, maneuver in orbit and dock to the space station, as well as validate all systems perform as expected,” NASA said in a statement.

Boeing is expected to send a company pilot aloft with a NASA crewmate for the CST-100’s first test flight. Company officials have not said who might be on board, but many believe it likely will be Chris Ferguson, commander of the final shuttle mission, who now spearheads Boeing’s commercial crew program.

It’s not yet clear whether SpaceX plans to fly a company employee or whether the first piloted test flight of a human-rated Dragon will include two of the NASA astronauts named Thursday.

All four astronauts have extensive flight test experience. Williams, a Naval Academy graduate and military helicopter pilot, has logged more than 3,000 hours flying more than 30 different types of aircraft. She also logged 322 days aboard the International Space Station during two long-duration stays, including more than 50 hours of spacewalk time.

Hurley is a former Marine colonel with more than 4,500 hours flying time in a variety of high-performance aircraft. He spent more than 28 days in space during two shuttle flights and flew with Ferguson as pilot of the final shuttle mission in 2011.

Boe is an Air Force colonel with 5,000 hours flying time and nearly a month in space during two shuttle flights. Behnken, also an Air Force colonel, served as NASA’s chief astronaut for the past three years. He is a veteran flight test engineer with 1,300 hours of flight time and 29 days in space on two shuttle missions. He also logged more than 37 hours of spacewalk time helping build the International Space Station.

“It’s really critical for the United States to regain its own launch capability, and the commercial crew program will allow us to do that,” Williams said. “We’re going to be able to (launch) Americans and our international partners from the U.S. to the International Space Station. That’s going to allow us to further our abilities, advance our technology so we can build the next generation of spacecraft for the next generation of space explorers.”

NASA began planning for commercial crew ships in the wake of the Obama administration’s 2010 decision to focus the space agency on deep space exploration and to turn “routine” flights to low-Earth orbit over to private industry.

Eight companies competed in initial development contracts and in the end, Boeing and SpaceX were chosen to build and launch the CST-100 and Dragon commercial ferry craft.

Boeing plans an unpiloted test flight in early 2017, followed by a pad abort test to demonstrate the ability of its on-board propulsion to pull the craft away from a malfunctioning booster. Assuming all that goes well, the first piloted test flight will come in late 2017.

SpaceX already has carried out a successful pad abort test and plans an unpiloted test flight in late 2016, followed by an in-flight abort test. The first crewed flight of a Dragon capsule is expected sometime in 2017.

But those schedules depend on funding, and committees in the House and Senate have voted to cut next year’s budget for the commercial crew program. The Obama administration asked for $1.2 billion, but the Senate has indicated it wants to cut $325 million while the House has weighed in with a proposal to reduce funding by $225 million.

NASA managers have repeatedly said any such shortfall would delay the initial flights, extending U.S. reliance on Russian Soyuz spacecraft for rides to and from the space station. In a blog post, NASA Administrator Charles Bolden said initial commercial crew flights already have been delayed by earlier cuts.

“Had we received everything (the Obama administration) asked for, we’d be preparing to send these astronauts to space on commercial carriers as soon as this year,” he said. “As it stands, we’re currently working toward launching in 2017, and today’s announcement allows our astronauts to begin training for these flights starting now.”

Bolden said more than 350 U.S. companies in 36 states are working on the commercial crew program and “every dollar we invest … is a dollar we invest in ourselves, rather than in the Russian economy.”

“Our plans to return launches to American soil also make fiscal sense,” he continued. “It currently costs $76 million per astronaut to fly on a Russian spacecraft. On an American-owned spacecraft, the average cost will be $58 million per astronaut. What’s more, each mission will carry four crew members instead of three, along with (220 pounds) of materials to support the important science and research we conduct on the ISS.”