Fully recovered from a computer hiccup that disrupted science observations this weekend, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft will resume imaging of Pluto on Tuesday, a week before the plutonium-powered probe zooms less than 7,800 miles from the unexplored dwarf planet at the frontier of the solar system.

Officials said Monday the glitch that put New Horizons into safe mode Saturday will not impact the spacecraft’s flight plan leading up to the July 14 encounter with Pluto.

It was just a “speed bump” on the way to Pluto, said Alan Stern, New Horizons’ principal investigator at the Southwest Research Institute on Boulder, Colorado.

Stern said any adjustments to New Horizons’ upcoming operations, which were meticulously planned and tested, would be a “freshman mistake.”

Programmed commands installed in the probe’s computer will automatically kick off a series of plasma, spectral and imaging observations of Pluto, its moons and the environment around New Horizons at 12:34 p.m. EDT (1634 GMT) Tuesday, mission managers said.

New Horizons went into safe mode Saturday when the spacecraft’s systems became overloaded while attempting to simultaneously compress science data for eventual downlink to Earth and load a command sequence into the probe’s primary computer for the mission’s July 14 flyby of Pluto.

“We were doing multiple things on the processor, on the computer and on the spacecraft at the same time,” said Glen Fountain, New Horizons’ project manager at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

Ground controllers were trying to clear room on New Horizons’ solid-state recorders for fresh science data expected to be collected in the coming days. Some old data was still on the recorder, so scientists wanted to compress the information for storage until it can be sent back to Earth after the flyby.

The science data compression overlapped with the writing of future commands into the computer’s flash memory, and the spacecraft was overwhelmed.

“The computer was trying to do two things at the same time, and the two were more than the process could handle at one time, so the processor says, ‘I’m overloaded,’ and then the spacecraft did exactly what it was supposed to do,” Fountain said.

New Horizons switched to its backup computer, stopped ongoing science observations and radioed Earth for help. The fix turned out to be relatively straightforward, Fountain said, and engineers restored New Horizons to normal operations Sunday.

As a precaution, mission managers decided to hold off on resuming science observations until Tuesday. In the meantime, engineers have finished housekeeping measures to prepare for the final flyby sequence, which New Horizons will execute autonomously beginning Tuesday, according to Stern.

Stern said the final science sequence is now installed into New Horizons’ primary and backup computers, governing the craft’s every turn, switch and command until July 16, two days after the probe’s closest approach to Pluto. Controllers in Maryland also erased segments of the probe’s solid-state recorders to prepare for the glut of data coming in over the next nine days.

Officials are not concerned about a recurrence of the safe mode.

“These events that came together, both the compression of a lot of data and a burn to flash (memory), those two events will not happen concurrently again,” Fountain said. “In fact, we do not do another burn to flash through the encounter.”

Even if New Horizons runs into another computer error, code written in the command sequence will trigger an automatic reset without putting the spacecraft into safe mode, allowing science operations to resume within minutes without intervention from engineers on the ground.

New Horizons and Pluto are 3 billion miles from Earth, and it takes nearly 9 hours for radio signals to make the round-trip journey. The communications leg means there is little ground controllers can do in the most critical phase around closest approach, which is set for a few seconds before 7:50 a.m. EDT (1150 GMT) on July 14.

The New Horizons team lost about 30 science observations in the three-day interruption, including black-and-white and color imagery from the probe’s LORRI telescope and Ralph camera.

“When you rack that all up, (we lost) about 30 observations altogether, and that’s out of a total of 496 observations to be made between July 4 and end of close approach operations July 16,” Stern said. “That’s about 6 percent of the observations by count, but scientifically, we weight the observations by how close they are to the planet, so these observations very far away are not nearly as important as those in the Pluto system, where we’ll be about 100 times closer than we were back this weekend.”

When weighing the relative importance of the science, Stern said the lost observations account for far less than 1 percent of the mission’s total research output.

As of Monday, New Horizons was nearly 6 million miles from Pluto and closing at more than 8.5 miles per second. Much better views of Pluto are just around the corner, Stern said.

“We made a decision to sacrifice all of those (long-range science observations), and to not distract the team to try to get a few extra observations made at a great distance, and instead to focus entirely on spacecraft recovery, getting the flyby load up and verified, getting the checksums back to the ground, and then to do a fairly large number of preparatory operations that were required to set us up to transition to the flyby load,” Stern said.

“We made the decision, and I think it was a really good one, to focus … on the cake and not worry too much about the icing, which is these distant observations,” he said.

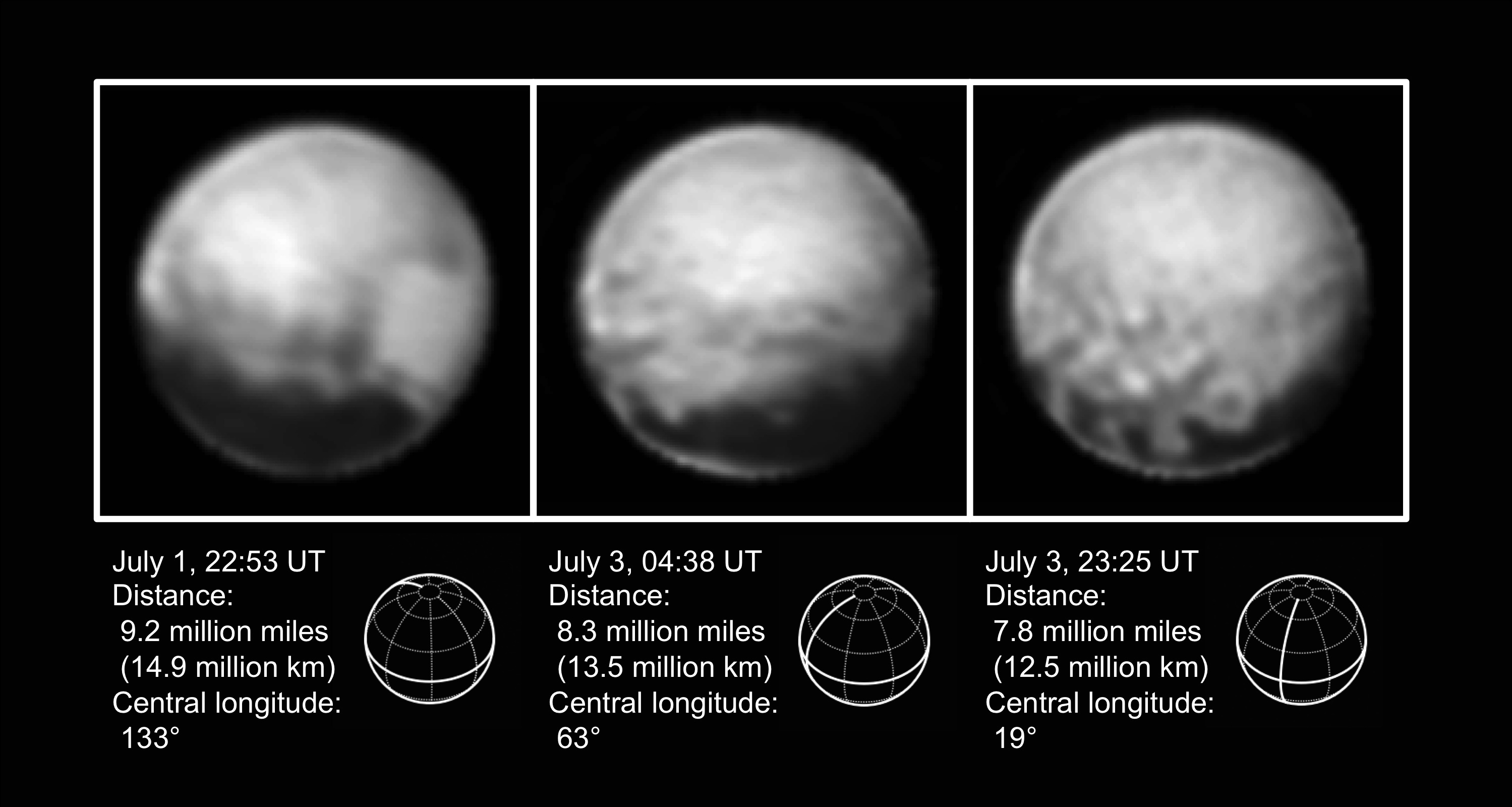

Scientists also unveiled fresh images of Pluto on Monday captured before this weekend’s computer glitch. New Horizons’ LORRI telescope took the three photos between July 1 and July 3, and NASA released a colorized version of a July 3 image using color data from the spacecraft’s Ralph camera taken earlier during the probe’s approach to Pluto.

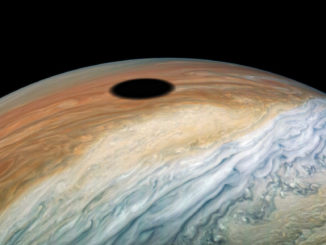

New Horizons is zipping toward Pluto from above the dwarf planet’s northern hemisphere, so Pluto’s equator appears near the bottom of the disk pictured in the imagery.

While the spacecraft will retain most of the data it collects inbound to Pluto for playback later, scientists have identified key spectral data and imagery to be downlinked to Earth daily through July 13.

“We spend most of the time collecting data, and then only a little bit of time sending data back,” Stern said. “What you will see every day is either images or spectra, or in some cases, other data types like the plasma data, coming to the ground day by day.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.