The European Space Agency revealed plans Thursday to build and launch a joint space weather research satellite with China and announced three finalists for Europe’s next standalone science mission.

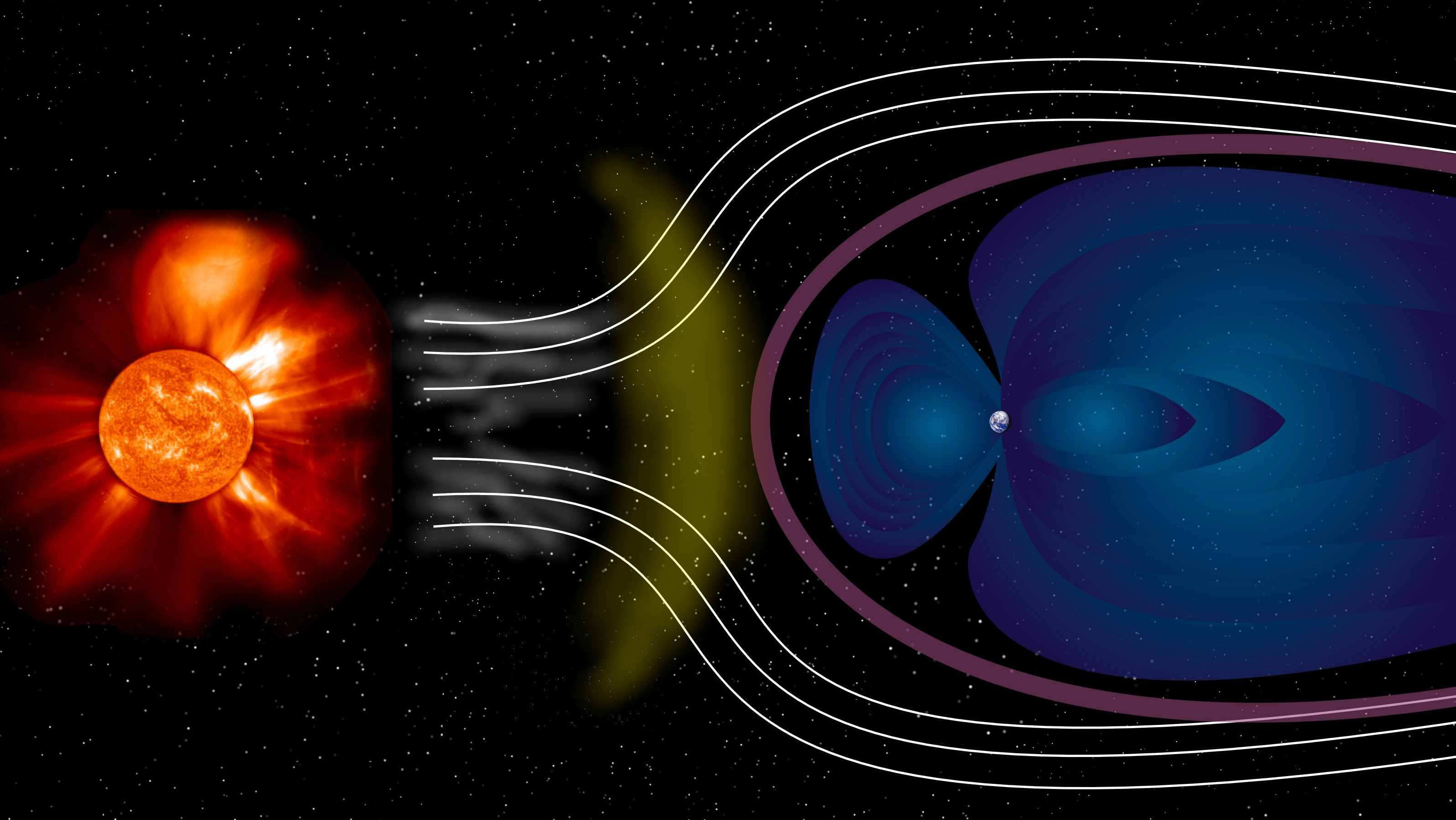

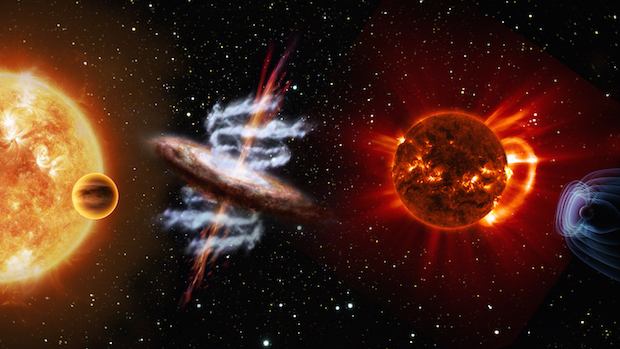

European and Chinese scientists recommended development of a spacecraft to monitor the interaction between the sun’s supersonic solar wind and Earth’s magnetosphere — a magnetic bubble that blocks dangerous radiation from reaching the planet’s surface.

The interplay between the solar wind and the magnetosphere drives space weather, which generates the colorful auroral displays over Earth’s poles and can interfere with satellites, radio communications and electrical grids.

The Solar Wind Magnetosphere Ionosphere Link Explorer, or SMILE, mission should be ready for launch in 2021.

“The goal of SMILE is to take the first pictures and movies of the Earth’s magnetosphere: the protective ‘bubble’ that the Earth’s magnetic field forms around us in space,” said Jonathan Eastwood, a collaborator on the SMILE project from Imperial College London. “Understanding how the magnetosphere works is crucial for forecasting ‘space weather’ which can affect human activity and technology both in space and on the ground.”

A mission concept presented to ESA called for a European-built spacecraft to blast off aboard a Chinese Long March 2C rocket into a high-inclination elliptical orbit ranging up to 80,000 miles above Earth at its farthest point.

SMILE’s unique orbit and sensor suite will allow the mission to undertake simultaneous monitoring of the content of the solar wind, its collision with Earth’s magnetosphere, and bursts of global auroras in day and night.

“Getting a global view for the first time in this way will transform our understanding of how the magnetosphere works,” Eastwood said in a press release.

SMILE is led by scientists at University College London and the Chinese National Space Science Center.

ESA and the China Academy of Sciences crafted a framework for a joint mission in 2014.

It follows Double Star, the first collaborative science project between Europe and China. Two Double Star satellites launched in 2003 and 2004 on a mission similar to SMILE, focusing on the response of Earth’s magnetosphere to solar activity.

The proposed SMILE spacecraft will carry X-ray and ultraviolet imagers to observe the boundaries of the Earth’s magnetosphere and auroral bands over the planet’s polar regions, and a particle detector and magnetometer to measure plasma streaming from the sun in the solar wind and track changes in the magnetic field around the satellite.

“SMILE will investigate the sun’s interaction with the Earth’s magnetic environment in a unique manner, never attempted before: using the novel approach of imaging in X-ray, whilst measuring the UV aurora and the properties of the solar wind at the same time,” said Graziella Branduardi-Raymont, co-leader of the SMILE project at UCL. “SMILE will give us the opportunity to understand the processes from beginning to end and predict the effects of space weather events in a way unmatched so far.”

Previous space weather research probes have recorded conditions around the spacecraft, a type of data scientists call in situ observations. SMILE is different because it will build on a recent discovery that the magnetosphere emits X-rays, which allows instruments to get a more comprehensive picture, scientists said.

SMILE’s instrument payload would be primarily built in Britain, Canada and China. Scientists in Finland and the United States are also participating.

The mission’s projected cost is 92 million euros, or $103 million at current exchange rates. ESA and China are expected to contribute equal funding to the project.

Top scientific advisors in Europe and China picked SMILE from 13 proposals submitted by joint Chinese-European science teams for missions focusing on astrophysics, heliophysics and fundamental physics, according to ESA.

The ranking of the SMILE mission above the competing proposals starts a six-month study of the mission prior to its formal selection by European and Chinese authorities in November.

Two more years of detailed analyses will follow before officials approve full development and construction of SMILE in 2017 ahead of its planned launch in 2021.

In a separate announcement Thursday, ESA unveiled its top three picks for a new “medium-class” science mission due for launch in 2025.

The three candidate missions — ARIEL, THOR and XIPE — were culled from a list of 27 proposals. They will now undergo thorough evaluations before ESA officials decide on one project to proceed toward launch.

One of the finalists will become the fourth medium-class mission in ESA’s Cosmic Vision program, which divides future European astrophysics and interplanetary probes into small, medium and large projects.

ESA set a rigid cost cap of 450 million euros — about $500 million — for the mid-range space mission. Scientists said the cost limit kept interplanetary missions out of the running in this selection round.

If approved for flight, the UK-led ARIEL observatory would use a 2.9-foot (90-centimeter) infrared telescope to analyze the atmospheres of around 500 known planets circling other stars.

A scientific consortium headquartered in Sweden proposed the THOR mission, which would address unanswered questions about the turbulent processes that heat up and accelerate plasma around the Earth, the sun and other stars.

XIPE is an X-ray observatory designed to detect emissions from supernovas, galaxy jets, black holes and neutron stars. XIPE would be the first space mission with the sensitivity to detect the polarization of X-ray sources, according to ESA.

The first three medium-class Cosmic Vision projects are the Solar Orbiter probe set for launch in 2018, the Euclid mission to explore the role of dark energy in the universe beginning in 2020, and the PLATO planet-hunting telescope scheduled to fly in 2024.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.