With a commitment from the Obama administration finally in hand after more than a decade of studies and concept papers, NASA expects to give the green light this year for development of a robotic probe to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa that could launch as soon as 2022.

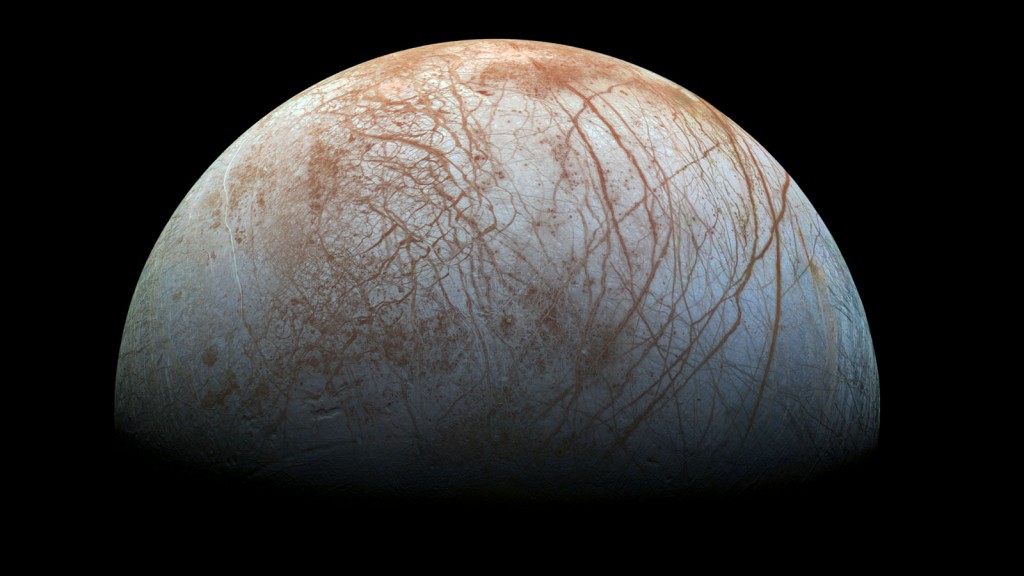

“It’s a tremendous opportunity for us to be able to look at a potentially habitable world around a giant planet,” said Jim Green, director of NASA’s planetary science division.

One concept led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory is the favorite to win NASA’s backing.

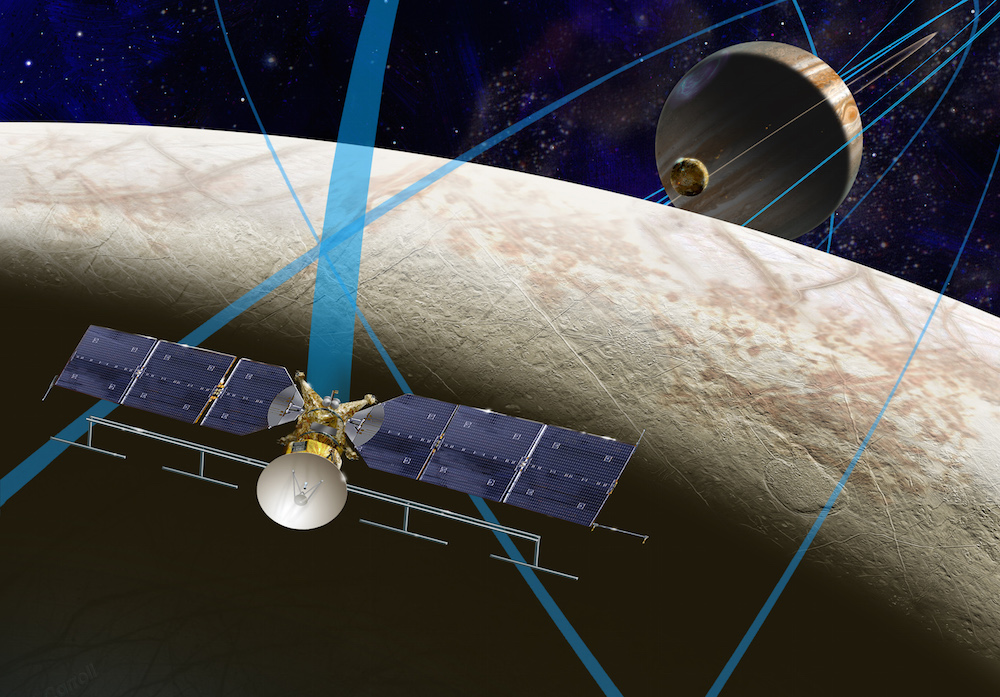

The Europa Clipper mission came out of a multi-year study to slash the cost of a mission to study the enigmatic moon, eventually settling on a projected price tag near $2 billion — excluding launch costs — less than half the estimated cost of a Europa probe published in a decadal survey report by the National Research Council in 2011.

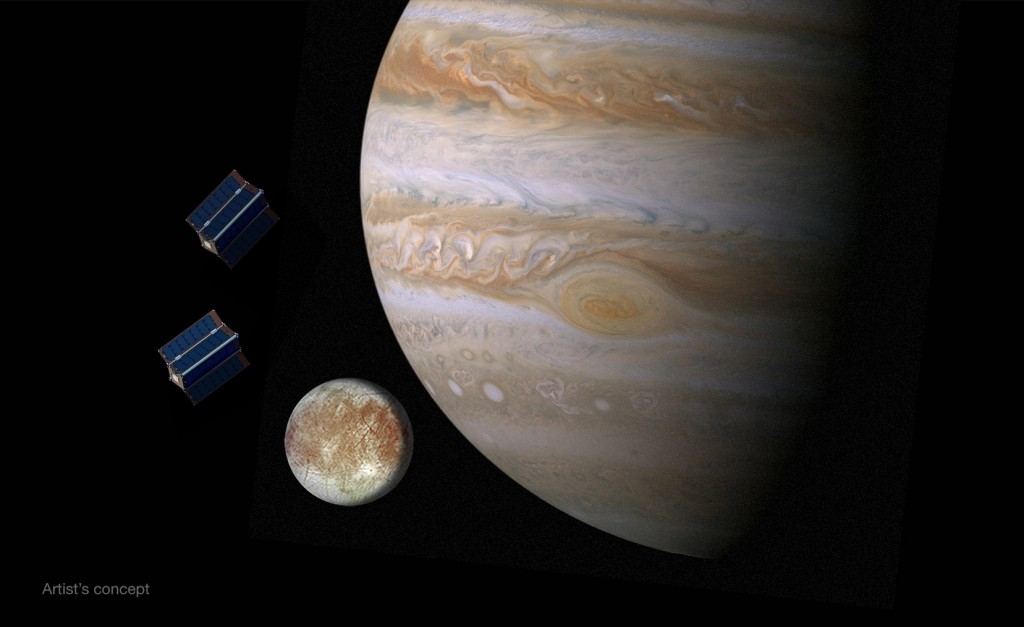

Scientists and engineers found savings in switching the probe from a nuclear-powered design to a solar power source and crafting a mission to fly by Europa dozens of times instead of entering orbit around the icy moon.

Officials say the Europa Clipper concept may need some tweaks, but it gives NASA a good starting point for development expected to start after it wins programmatic approval in a milestone expected as soon as mid-2015.

The milestone, known as Key Decision Point A (KDP-A) in NASA’s parlance, will mark the start of full-scale development of the Europa probe. Decisions on scientific instrumentation, mission design, a launch vehicle and launch date, and international partnerships will follow.

“Europa Clipper has had quite an important evolution,” Green said in a Feb. 19 meeting of NASA’s Outer Planets Assessment Group. “It is a proof of concept that says we can do it, and it’s not a $4 billion mission as we studied and discussed at the decadal, so it has made major progress.”

Barry Goldstein, who leads the Europa Clipper studies as pre-project manager at JPL, said the mission passed a major hurdle in September, when reviewers deemed the concept mature enough for consideration in NASA’s mission portfolio.

Congress has backed the Europa mission with $255 million over the last three years, an order of magnitude more than the White House requested over the same period.

“Given the fact that we have this funding, we’re proceeding on this path and not slowing down,” Goldstein told the OPAG meeting Feb. 19.

The Obama administration is asking Congress for $30 million — enough to formally turn on development of a Europa mission — in fiscal year 2016, which begins Oct. 1.

“Congress has been quite generous,” Green said, adding the funding approved by lawmakers the last three years gives the Europa project a “really rich start” compared to the beginnings of most of NASA’s other robotic science missions.

“It is highly unsuual that the mission concepts that enter (formulation and development) are as mature as we have in looking at Europa,” Green said.

NASA plans to take the first step at selecting instruments to fly on the Europa mission in April, when the space agency will award funding to the top-rated science teams to refine their proposals and reduce the risks of developing the sensors.

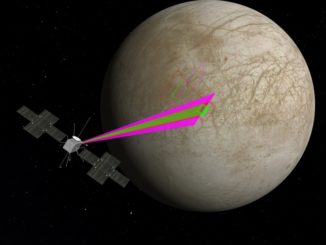

Final instrument decisions are expected in 2016, giving NASA time to evaluate what set of sensors should be flown to Europa in hopes of probing the ocean thought to lie below the moon’s global ice sheet. The mission could also sample watery plumes that may exist over Europa’s south pole, where a flyby probe could dash through material lofted from below the surface.

Scientists announced in 2013 that the Hubble Space Telescope detected evidence for the plumes, thrusting a mission to Europa back on the science community’s agenda after being overshadowed by NASA’s push toward Mars.

Follow-up observations by Hubble are planned to try and confirm the plume detection.

“I can’t overemphasize the importance of the Hubble observations (of the plumes) that allowed us to renew the conversation about Europa being an active world,” Green said.

While Green said the Europa Clipper study has “popped to the top” of the Europa mission concepts considered by NASA, the design could require some fine-tuning to accommodate all the objectives the agency wants to accomplish.

“Perhaps additional instruments need to be brought on to investigate the plume,” Green said, adding that NASA is examining ideas to deploy CubeSats or drop a lander or impactor to Europe’s surface.

Green said NASA has asked the European Space Agency if it is interested in contributing to the Europa mission.

ESA plans to launch its own probe to Jupiter in 2022 to conduct multiple flybys of the giant planet’s moons Ganymede, Callisto and Europa before eventually looping into orbit around Ganymede.

While ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, or JUICE, mission will fly by Europa twice, NASA’s Europa Clipper concept could zip past it 45 times.

ESA participated in NASA’s last flagship-class mission to the outer solar system. The European-built Huygens lander accompanied the Cassini spacecraft to Saturn, then parachuted to a landing on the moon Titan in 2005.

NASA and ESA planned to partner on a joint mission to the Jupiter comprising two spacecraft, one to orbit Europa and another to circle Ganymede. But budget limitations kept the U.S. space agency from going forward with its part of the mission, which had a projected cost of nearly $5 billion.

ESA moved forward with the European-led JUICE mission, and NASA went back to the drawing board before eventually coming up with the Europa Clipper proposal.

“ESA’s really been our best partner,” Green said. “They’ve been fabulous working with us. We’ve had ups and downs in the past, but all seems to be forgiven and we’re right back together. I want to give them an opportunity to be part of this mission. We shouldn’t let that go, and we have to let that evolve.

“There are a number of concepts that we’ve asked them to look at, and they’ve started to look at them,” Green said.

NASA is officially targeting launch of the Europa probe in the mid-2020s, but Goldstein said the Europa Clipper concept is far enough along to potentially be ready for flight by June 2022, when the positions of Earth and Jupiter make the journey possible.

“We’re a mission that will launch some time in the early-to-mid-2020s,” Goldstein said. “Our best case scenario is launching in an opportunity that opens up in May to June of 2022, and we’re holding that.”

Goldstein said engineers have studied launching Europa Clipper on NASA’s Space Launch System — a behemoth rocket designed to launch astronauts into deep space — or the most powerful version of United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5 rocket with five strap-on solid rocket boosters.

The mission concept review board in September concluded the SLS launch option was “far superior” to other alternatives because it would allow the probe to fly directly to Jupiter in less than two years. Launching on a smaller rocket would require gravity assist flybys of Venus and Earth, adding three-and-a-half years to the voyage.

But lifting off aboard the SLS would be more costly — the Europa Clipper study assumed $500 million — and NASA would have to insert the Europa launch into the heavy-lift rocket’s manifest between launches with crews.

The Europa Clipper team opted to go with a solar-powered design instead of using a plutonium power generator, a decision Goldstein said saves money and still leaves plenty of margin for growth if the spacecraft needs more electricity or gets bigger.

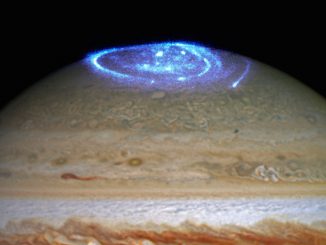

Goldstein said the Europa team is following the progress of NASA’s Juno mission, which is fitted with solar panels and on the way to Jupiter, with arrival in orbit set for July 2016. Juno will study Jupiter’s magnetic field and internal structure, and the probe will set a record for the most distant mission to rely on solar energy.

Solar cells at Jupiter’s distance from the sun produce a fraction of the electricity as they do at Earth.

Officials are still evaluating whether it will be better to use solar cells flown on Juno or switch to a more high-tech design to give out more power.

“We can either cash that in with less area for the (solar) arrays or more power for the system, to be determined at this point,” Goldstein said. “But we’re not counting on that new technology. We wanted existence proof to show that we had what we needed to make the jump away from (nuclear power).”

Officials hope to decide between the old or new solar cell technology by the middle of 2015, then NASA could begin buying test and flight units as part of the mission’s long-lead purchases, according to Goldstein.

Other upcoming milestones include the build-up of a testbed to test the spacecraft’s avionics, and tests of components for the mission’s thermal control system.

“We don’t have significant engineering risks on the baseline engineering subsystems,” Goldstein said.

But Europa Clipper’s instrument package, expected to include spectrometers, cameras, an ice-penetrating radar and potential daughter probes, could have a tough time handling the harsh radiation environment at Jupiter.

“When the instruments are selected, they are subjected to a much more harsh environment than the rest of the engineering system,” Goldstein said. “Where I think our biggest challenges are going to be is in the sensors and the other elements that are not cocooned inside the vault that we’ve created in this architecture. I’m really worried about the challenges the instruments are going to have in development.”

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.