STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS “SPACE PLACE” & USED WITH PERMISSION

NASA expects to spend some $5 billion underwriting development of commercial spacecraft built by Boeing and SpaceX to carry astronauts to and from the International Space Station, officials said Monday, ending sole reliance on the Russians for crew ferry flights and eventually lowering the average cost per seat to around $58 million.

Gwynne Shotwell, president and chief operating officer of Space Exploration Technologies, or SpaceX, said her company’s upgraded Dragon V2 ferry craft should be ready for an initial unpiloted flight to the space station in late 2016 with the first crewed flight, likely carrying a SpaceX test pilot and a NASA astronaut, in early 2017.

John Elbon, vice president and general manager of Boeing Space Exploration, said his company’s CST-100 spacecraft is expected to be ready for an uncrewed test flight in April 2017, followed by a crewed flight, with a Boeing pilot and a NASA astronaut, in the July 2017 timeframe.

Both companies must complete the crewed and uncrewed test flights before NASA certification, which will pave the way for the start of operational crew rotation and cargo delivery flights to the International Space Station later in 2017. Until then, NASA will continue to rely on Russia’s Soyuz spacecraft to carry U.S. and partner crew members to and from the lab complex.

“Commercial crew is incredibly important to the space station, it’s important to reduce the cost of transportation to low-Earth orbit so that NASA has within its budget the capability to develop means to explore beyond low-Earth orbit,” Elbon said during a news conference at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. “And importantly, I think, it’s beginning a whole new industry. … We’re making great progress on the program.”

Said Shotwell: “Our crew Dragon leverages the cargo capability that we’ve been flying successfully to the International Space Station. However, we understand, and we’ve been told, that crew is clearly different. So there are a number of upgrades that we’ve been working for the past few years to assure that this crew version of Dragon is as reliable as it can possibly be. Ultimately, we plan for it to be the most reliable spaceship flying crew ever.”

In the wake of the space shuttle’s retirement, NASA started a competition to build a commercial crewed spacecraft, with the first in a series of contracts intended to encourage innovative designs for reliable, affordable transportation to and from low-Earth orbit.

Last September, NASA announced that Boeing had won a $4.2 billion Commercial Crew Transportation Capability (CCtCAP) contract to continue development of the company’s CST-100 capsule while SpaceX would receive $2.6 billion to press ahead with work to perfect its futuristic Dragon crew craft.

A third competitor, Sierra Nevada, was left out, and the company filed a protest with the General Accountability Office, arguing its Dream Chaser spaceplane was unfairly passed over. But the GAO ruled earlier this month that NASA’s selection of Boeing and SpaceX was justified, clearing the space agency to proceed with the CCtCAP contracts.

SpaceX and Boeing hold contracts covering two test flights and two operational missions per company with options for additional operational missions between them.

Boeing’s CST-100 spacecraft is a state-of-the-art, reusable capsule incorporating weld-less fabrication, flight proven navigation software, powerful “pusher” escape rockets to propel the capsule away from a malfunctioning booster and a parachute-and-airbag landing system.

For NASA flights, the spacecraft will be used to carry four astronauts at a time to the space station, along with critical cargo. It will be launched atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket, one of the most reliable boosters in the U.S. inventory.

Elbon said construction has started on a launch pad crew access tower and work platforms needed to service CST-100s in a former shuttle processing hangar. A simulator will be installed at the Johnson Space Center in the same building that once housed shuttle flight simulators and Boeing is working out procedures to use NASA’s mission control center for ascent, rendezvous and re-entry.

“The flight software will be delivered later this summer, we’ll have the simulator running with the flight software and flight computers and 26 of the 34 flight displays,” Elbon said. “So there will be a real opportunity for the crew to interface with that software and understand how the vehicle’s going to operate.”

Boeing plans a launch pad abort test in February 2017 “where we’ll fully check out the abort system” before staging the first unpiloted test flight to the space station the following April. Elbon said Boeing should be ready for the first crewed test flight in July 2017. Assuming the test flights go well and NASA certifies the CST-100, Boeing expects to be ready for its first operational mission in December 2017.

SpaceX already flies to the space station under a $1.6 billion contract with NASA for a dozen uncrewed cargo flights using the company’s Dragon capsule and Falcon 9 rockets.

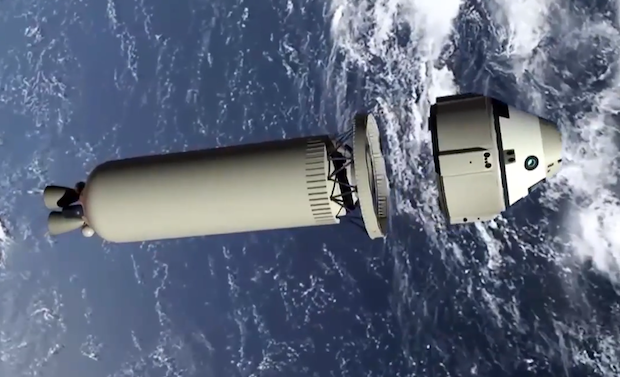

The crewed version of the spacecraft will be able to carry up to seven astronauts — typically four for station missions — and features futuristic pull-down flat-screen displays, a powerful escape rocket system and sophisticated computer control. As with the automated cargo ships, the crew capsules will be launched atop Falcon 9 boosters.

Shotwell said SpaceX is gearing up for a pad abort test in the next month or so when a Dragon spacecraft will be shot off the launch pad using its escape rockets to demonstrate the ability to pull a crew away from a catastrophic low-altitude booster malfunction. A second abort test will be carried out later this year to demonstrate escape during the most aerodynamically stressful regions of powered flight.

“The Integrated launch abort system is critically important to us, we think it gives incredible safety features for a full abort all the way through ascent,” Shotwell said. SpaceX founder and chief designer Elon Musk hopes to eventually use the abort system for rocket-powered landings at the end of a mission, but initial flights will splash down in the ocean much like Dragon cargo missions.

While SpaceX is a relative newcomer to the rocket industry, Shotwell said the company will have launched more than 50 Falcon 9 rockets by the time astronauts strap into a Dragon V2 for the first piloted test flight. She said SpaceX will install a simulator at the Johnson Space Center for crew training, but likely will monitor ascent, rendezvous and re-entry from the company’s Hawthorne, Calif., rocket plant where Dragon supply flights are managed.

“We anticipate doing our uncrewed mission to the International Space Station on this upgraded crew vehicle later in ’16, shortly followed thereafter with our crewed flight in early 2017, as shortly as we can make it and still maintain reliability and safety,” she said. “We certainly understand the incredible responsibility we’ve been given to build the systems necessary and capable of flying crew.”

Along with ferrying astronauts to and from the space station, the Boeing and SpaceX capsules also will be able to serve as lifeboats for station crew members, remaining attached to the station for more than 200 days at a stretch to give U.S. and partner astronauts a way home in an emergency.

The new spacecraft will be the first American vehicles to carry astronauts on NASA-sanctioned flights since the space shuttle’s last mission in 2011 and the first built under more commercially structured contracts intended to lower costs.

The CST-100 and upgraded Dragon also will end America’s reliance on Russian Soyuz spacecraft for access to the International Space Station. Under NASA’s latest contract with Roscosmos, the Russian federal space agency, U.S. seats cost around $70 million each. Kathy Lueders, manager of NASA’s commercial crew program, said the agency eventually will save, on average, more than $10 million a seat using U.S. spacecraft.

“Overall, when we go through the whole development activity … we’ll have invested about $5 billion,” she said. “In addition, when you look at pricing for the missions across the five years we have pricing for, we’re able to get an average seat cost of about $58 million per seat.”

But NASA’s use of Soyuz spacecraft will not end with the advent of U.S. space taxis.

Mike Suffredini, manager of the space station program at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, said in a Jan. 15 interview with CBS News that NASA still plans to use one seat per Soyuz for the duration of the station program. The Russians, likewise, will be able to launch a cosmonaut on each U.S.-sponsored flight.

Assuming both parties ultimately agree, “the Russians will fly twice a year, or whatever rate they need to do their job, and we will have a crew member on each of their flights,” Suffredini said. “We will fly ours at whatever rate we think we need to do our job and they will put a single crew member on it.”

During the news conference Monday, NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden said “I don’t ever want to have to write another check to (the Russian federal space agency) Roscosmos after 2017, hopefully. That’s why I’m looking to John and Gwynne to deliver. You’ve heard both of them say they think they’ll be flying by 2017. If we can make that date, I’m a happy camper.”

But NASA has to be prepared for contingencies and the commercial crew schedule is optimistic. Space station planners do not yet know for sure when a commercial ferry craft will begin operational missions and orders for Soyuz seats must be placed three years in advance.

“So I’m about to tell (Roscosmos) whether I want seats in 2018 right now, and we don’t have any more insights (into commercial crew progress) really than the proposals,” Suffredini said. “So we’ve got to go get some seats.”

Longer term, he said NASA plans to continue flying on Soyuz after Boeing and SpaceX begin operational missions, but under a barter arrangement of some sort.

“We’re assuming two Russian seats a year and we’re assuming two Russians will fly in our seats per year,” Suffredini said. “And it’ll just be a quid pro quo, we won’t ask for compensation.”