Updated after BEAM installation.

The International Space Station’s robotic arm, under the control of engineers on Earth, extracted an experimental inflatable habitat from the trunk of SpaceX’s Dragon supply ship Saturday and attached it to the orbiting complex.

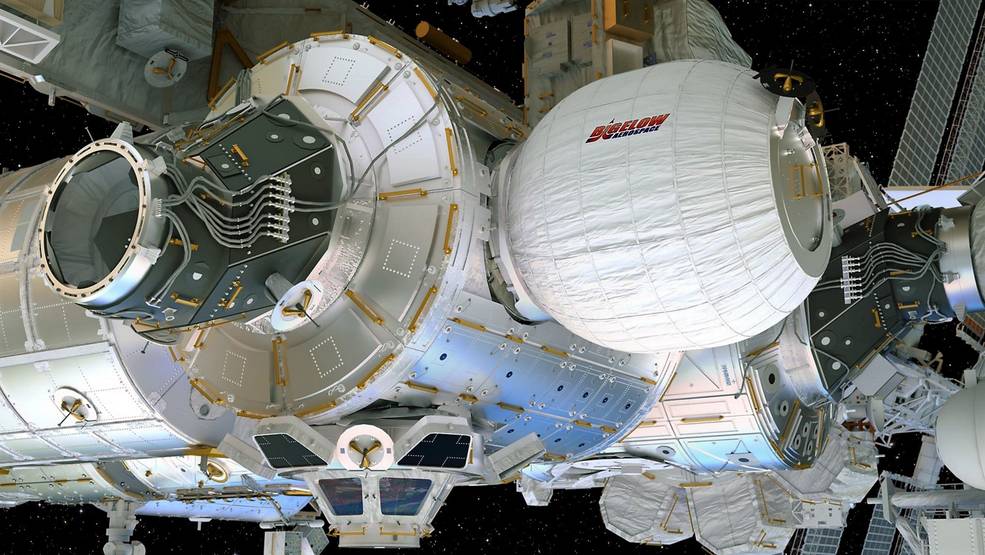

Made by Bigelow Aerospace, the new module will spend two years on the space station to prove the novel design’s worthiness for future commercial orbiting research labs and expeditions to deep space.

The Bigelow Expandable Activity Module, or BEAM, flew to the space station inside a SpaceX Dragon cargo craft last week. The flight was arranged between Bigelow and NASA, which is paying the Las Vegas-based company $17.8 million for the project.

Unlike the space station’s other modules, which are made of metal alloys, BEAM is made of reinforced fabric designed to be resistant to radiation and bombardment by tiny flecks of space junk and micrometeoroids.

One of the BEAM project’s objectives is to verify the inflatable module concept can withstand the rigors of spaceflight.

Engineers sent commands to unlatch BEAM from its mooring inside Dragon’s unpressurized trunk early Saturday, and the 58-foot robot arm, nicknamed Canadarm 2, removed the 3,115-pound (1,413-kilogram) module from the SpaceX supply ship around 2:15 a.m. EDT (0615 GMT).

The robotic arm maneuvered BEAM, which measures about about 5.7 feet (1.7 meters) long and nearly 7.8 feet (2.4 meters) in diameter in its stowed configuration, to a berthing port on the aft side of the the space station’s Tranquility module.

Berthing was complete at 5:36 a.m. EDT (0936 GMT), according to NASA spokesperson Dan Huot.

The module will be inflated around May 26, expanding to four times its current volume until it reaches the approximate dimensions of a family-sized tent. Space station managers want to wait to inflate BEAM until the research complex and its crew are in a quiet period without arriving or departing spacecraft.

Bigelow Aerospace intends to launch a module 20 times bigger to low Earth orbit in 2020 to form the centerpiece of a commercial human-tended space station for tourists and researchers to visit.

The habitat is made of a Vectran-like material, according to Lisa Kauke, BEAM’s deputy program manager at Bigelow Aerospace. NASA used similar materials in the airbags that cushioned the landings of NASA’s Mars Pathfinder, Spirit and Opportunity rovers.

After the module is inflated, astronauts will enter the habitat to install sensors to monitor conditions inside the module, tracking temperatures, radiation levels, and impacts from tiny micrometeoroids and space junk, according to Rajib Dasgupta, technical integration manager for the BEAM demonstration at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

The inflation dynamics are an unknown, officials said.

Sensors mounted on both sides of the module’s interface with the space station will measure how the deployment works.

“This type of architecture has never been flown before,” Robert Bigelow, founder of Bigelow Aerospace, said before last week’s launch of BEAM. “It has been bound up for over a year waiting for launch. We’re not 100 percent sure of its behavior. It is a testing station. That is the whole point here, in all respects.”

Bigelow Aerospace launched two small inflatable satellites in 2006 and 2007. Those missions, dubbed Genesis 1 and 2, performed beyond expectations, Kauke said.

“What we learned from both of those programs is that the technology works, and we proved our materials and our assembly processes,” Kauke said.

NASA and Bigelow are now demonstrating expandable module technologies for human spaceflight.

Inflatable structures have several benefits, chiefly the ability to launch modules inside the constrained size of existing rocket fairings. They are also lighter than conventional metallic modules.

Bill Gerstenmaier, chief of NASA’s human exploration and operations directorate, said last month that the space agency is eager to see the results of the BEAM demonstration.

“Does it meet all the things that it’s purported to meet? It’s supposed to have better micrometeoroid and debris protection, better thermal protection, better acoustics, and we’ll see if it has those,” Gerstenmaier said. “We’ll also understand how to use a fairly large volume, which we have not had experience with.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.