SpaceX scrubbed the first test launch of its huge new rocket Monday due to a frozen valve in the pressurization system on the 33-engine Super Heavy booster, delaying the widely-anticipated flight from South Texas until at least Thursday.

The company’s launch team fully loaded the 394-foot-tall (120-meter) rocket with more than 10 million pounds of methane and liquid oxygen propellants early Monday, but SpaceX engineers providing updates on a live webcast reported a problem with the first stage’s pressurization system around 17 minutes prior to a scheduled liftoff time of 8:20 a.m. CDT (9:20 a.m. EDT; 1320 UTC).

“A pressurant valve appears to be frozen, so unless it starts operating soon, no launch today,” tweeted Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder and CEO.

It turned out the valve problem was not resolved in time to proceed with liftoff from SpaceX’s Starbase launch complex in Cameron County, Texas. The rocket is the largest ever built, with 33 engines on a booster stage called Super Heavy, and six engines on the upper stage, known as Starship. The fully assembled rocket is also named Starship.

“The decision right now is that we are going to stop the launch for today,” said John Insprucker, a veteran SpaceX engineer speaking on the company’s live webcast. “We’re going to transition the launch attempt into a wet dress rehearsal.”

The propellant tanks on the Super Heavy booster and Starship upper stage need to be pressurized during the flight,

SpaceX continued loading super-cold methane and liquid oxygen into the rocket before the countdown stopped at T-minus 40 seconds, giving the launch team another chance to hone their procedures and verify all other launcher and ground systems were healthy.

“Learned a lot today, now offloading propellant, retrying in a few days,” Musk tweeted after SpaceX scrubbed the launch attempt.

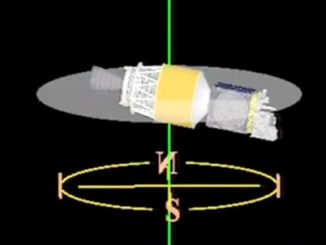

Starship uses an autogenous pressurization system in which heated oxygen and methane is routed back into the propellant tanks in a gaseous state to supply pressure, ensuring the liquid oxidizer and fuel smoothly flows into the Raptor engines. Musk said Sunday night that one challenge in the Starship design is making sure the pressurization gases do not get cold enough to liquify in the tanks.

SpaceX announced later Monday that the next launch attempt for the Starship test flight was scheduled for Thursday at 8:28 a.m. CDT (9:28 a.m. EDT; 1328 UTC), with a 62-minute launch window. It takes several days to replenish ground propellant tanks at Starbase, with numerous tanker trucks expected to deliver a fresh supply of methane, liquid oxygen, and liquid nitrogen to the launch base.

Musk said before the test flight there was a good chance of an abort on the first launch attempt.

“This is not like some sort of train leaving the station at precisely like 9:03 a.m. or something like that,” Musk said Sunday night in a pre-launch Twitter “Spaces” discussion with his subscribers. “It’s the first launch of a very complicated, gigantic rocket. … We’re going to be very careful, and if we see anything that gives us concern, we’ll postpone the launch.”

When it takes off, 33 Raptor engines will power the rocket off the pad with 16.7 million pounds of thrust at full throttle, according to SpaceX. That’s more than twice the thrust of NASA’s Saturn 5 moon rocket, and well over the power generated by NASA’s Space Launch System rocket for the Artemis moon program. It also surpasses the 10 million pounds of thrust from 30 engines that powered the Soviet Union’s N1 moon rocket on four failed launch attempts from 1969 through 1972.

On their first fully integrated test flight, the Super Heavy booster and Starship rocket, designed to eventually be fully reusable, will attempt to fly into space for the first time on an around-the world voyage culminating in the impact of the Starship vehicle in the Pacific Ocean north of Hawaii.

The Super Heavy booster, itself standing 226 feet (69 meters) tall, will provide the power needed to reach space in the first three minutes of the test flight. The Starship upper stage is designed to take over the mission at that point with six Raptor engines to accelerate to nearly orbital velocity before reaching a peak altitude of around 146 miles (235 kilometers).

SpaceX will attempt to reignite some of the Super Heavy booster’s 33 engines for two maneuvers to target a controlled vertical splashdown in the Gulf of Mexico around 20 miles (30 kilometers) east of the launch site. The Starship upper stage, protected by thermal protection system tiles, is supposed to re-enter the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean, but it won’t reignite its main engines, resulting in a hard impact in the sea.

The first test flight of the fully-assembled Starship rocket comes after a series of sub-scale lower-altitude atmospheric flight tests in 2019, 2020, and 2021. Those demonstrations primarily focused on testing Starship’s landing maneuver.

Once the rocket is proven, SpaceX wants to use the Starship vehicle to deploy the company’s Starlink internet satellites, flying heavier, next-generation versions of the broadband relay stations than the spacecraft now being launched by the smaller Falcon 9 rocket. An animation released from SpaceX showed the company’s concept for deploying Starlink satellites from a Starship vehicle in orbit, using a mechanism that works like a giant Pez dispenser.

SpaceX has also won a $2.9 billion contract with NASA to develop the Starship into a human-rated lander for the agency’s Artemis moon missions. A moon derivative of the Starship, assisted by Starship refueling tankers, will be utilized for a lunar landing with astronauts, an event NASA says could happen no earlier than 2025. SpaceX also has a deal with Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa to send a team of private citizens around the moon on a Starship flight.

Flights of the Starship beyond low Earth orbit will require the still-untested in-orbit refueling capability SpaceX is developing for the new-generation rocket.

There is no operational payload on the Starship’s first test flight in space. The rocket will not achieve orbit, and the vehicle’s payload bay door has been welded shut.

On future Starship flights, SpaceX plans to try catching the Super Heavy booster as it descends back to the launch pad, a breakthrough that would allow the company to reuse rockets faster than it can with the current generation of smaller Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets.

But the rocket for the first full-scale Starship test flight won’t be recovered for reuse.

“I would just like to set expectations low,” Musk said Sunday night. “If we get far enough away from the launch pad before something goes wrong, then I think I would consider that to be a success. Just don’t blow up the launch pad!”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.