SpaceX continued launching satellites for the Starlink internet network Friday, sending a Falcon 9 rocket aloft from Cape Canaveral with 56 more older-generation broadband spacecraft as ground teams troubleshoot problems with a batch of upgraded Starlinks launched last month.

The 56 satellites were packed on top of the 229-foot-tall (70-meter) Falcon 9 rocket for liftoff at 11:43:10 a.m. EDT (1543:10 UTC) Friday from pad 40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. Riding 1.7 million pounds of ground-shaking thrust from nine kerosene-fueled Merlin main engines, the Falcon 9 accelerated faster than the speed of sound in about a minute as it raced through a sunny sky heading downrange toward the southeast from Cape Canaveral.

Following a now-familiar routine, first stage of the rocket shut down its nine engines two-and-a-half minutes after liftoff, then dropped away to begin an arc toward SpaceX’s landing platform, or drone ship, positioned about 410 miles (660 kilometers) southeast of Cape Canaveral, or northeast of the Bahamas. The rocket, numbered B1067 in SpaceX’s inventory, reignited a subset of its engines to slow down for re-entry and landing, then settled onto the deck of the floating platform about eight-and-a-half minutes into the mission.

The recovery team will bring the rocket, now a veteran of 10 flights to space, back to Cape Canaveral for refurbishment ahead of a future mission. A separate SpaceX team in the Atlantic was on station to retrieve the two halves of the rocket’s payload fairing, or nose cone, after they parachuted into the sea.

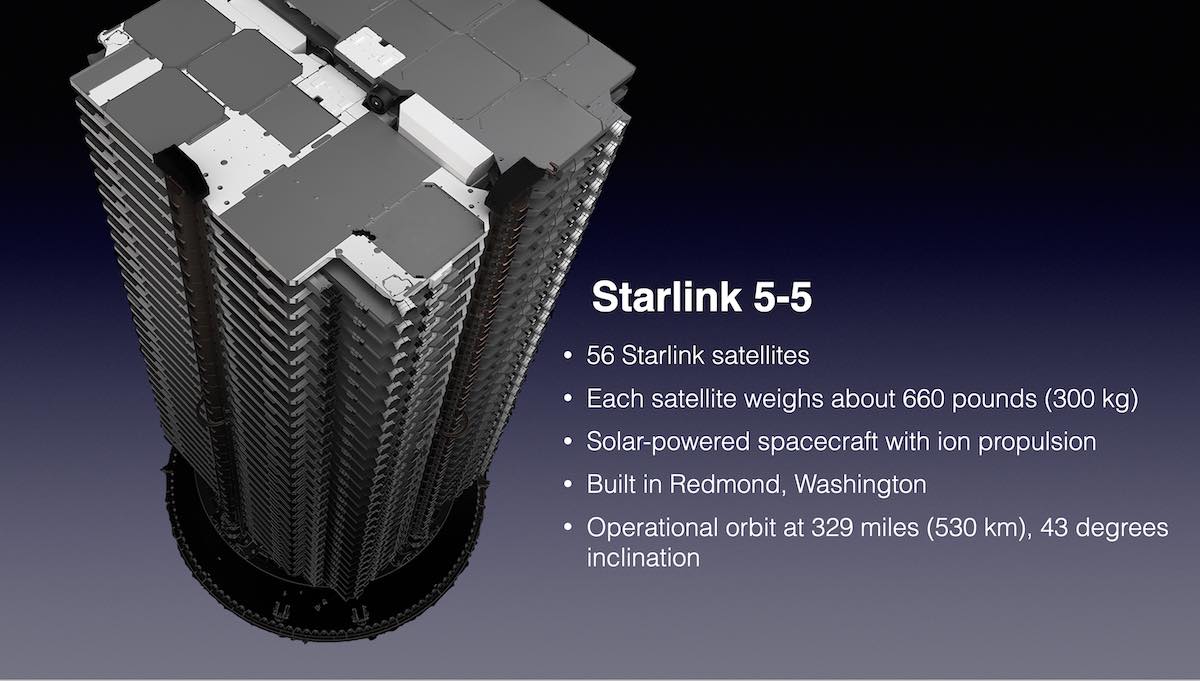

The Falcon 9’s second stage fired its single engine two times to inject the 56 Starlink satellites into an orbit about 200 miles (300 kilometers) above Earth, at an inclination of 43 degrees to the equator. SpaceX confirmed the successful deployment of the 56 spacecraft a little more than an hour into the mission.

The 56 spacecraft on Friday’s launch totaled about more than 17.4 metric tons, or more than 38,000 pounds, tying the record for the heaviest payload ever flown on a SpaceX rocket with a previous Starlink launch in January. The company’s engineers have experimented with engine throttle settings, fuel efficiencies, and another minor upgrades to stretch the Falcon 9’s lift capability.

Another Falcon 9 launch set for Wednesday from Cape Canaveral will also carry more than 50 Starlink internet satellites.

Liftoff of a Falcon 9 rocket with 56 more Starlink internet satellites, kicking off SpaceX’s 20th launch of the year. https://t.co/biik6N2uq6 pic.twitter.com/0t6MpaqR8h

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) March 24, 2023

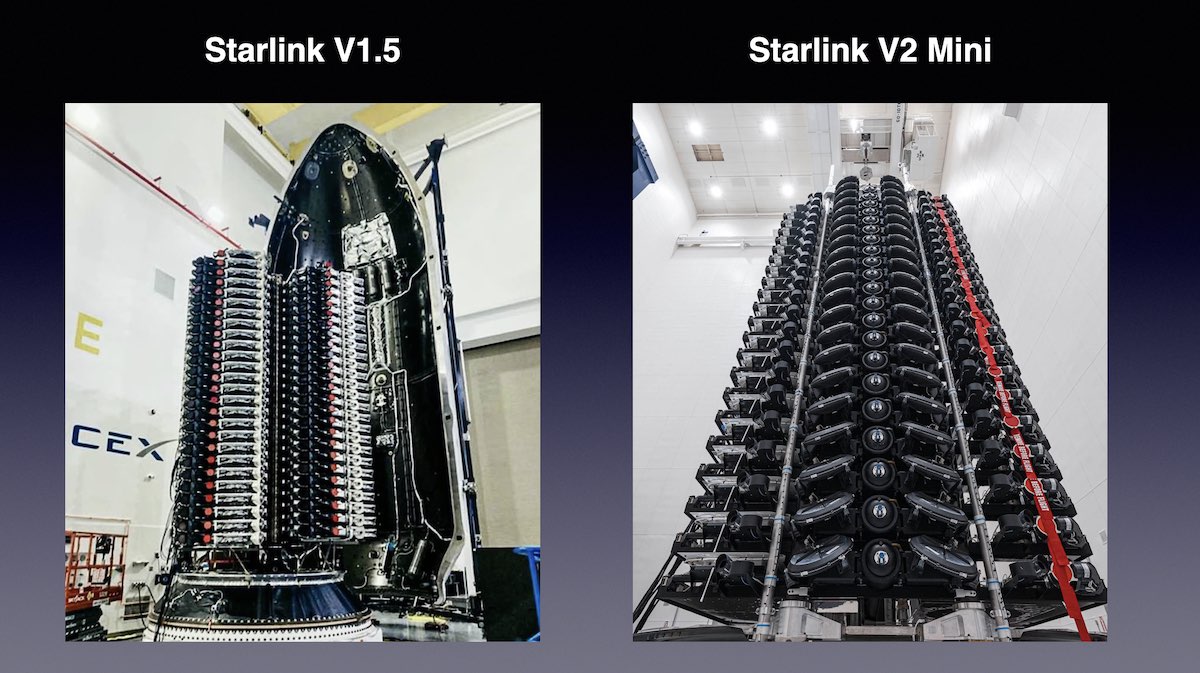

Friday’s launch and the SpaceX mission next week were originally slated to loft more batches of SpaceX’s larger, second-generation Starlink satellites. The second-generation “Starlink V2 Mini” satellites are fitted with improved phased array antennas and have four times the communications capacity of earlier generations of Starlink satellites, known as Version 1.5, SpaceX said.

The first group of 21 upgraded Starlink V2 Mini satellites launched Feb. 27 on a Falcon 9 rocket, which released the spacecraft into orbit at an altitude of about 230 miles (370 kilometers). Publicly-available orbital data showed the satellites raised their altitude to nearly 240 miles (about 380 kilometers), but the spacecraft began gradually descending in mid-March.

Starlink satellites typically activate their thrusters to begin maneuvering from their initial orbit, where they are deployed by the Falcon 9 rocket, to higher operating altitudes more than 300 miles above Earth. The stall in orbit-raising raised questions among some observers about the status of the new Starlink V2 Mini satellites.

“Lot of new technology in Starlink V2, so we’re experiencing some issues, as expected,” Musk tweeted Wednesday. He added that some of the Starlink V2 Minis satellites could be deorbited, while others will be “tested thoroughly” before boosting above the altitude of the International Space Station, which flies at 260 miles (420 kilometers) altitude.

The Falcon 9 launch Friday and the next flight from Florida on Wednesday were originally supposed to carry upgraded Starlink V2 Mini satellites, but SpaceX has swapped out those stacks of second-generation satellites for groupings of older Starlink V1.5 spacecraft. SpaceX has not confirmed if the problems with the first 21 Starlink V2 Mini satellites were the reason for the payload swaps on the next two Falcon 9 missions.

Friday’s launch was designated Starlink 5-5 in SpaceX’s launch sequence, and the mission set for March 29 is named Starlink 5-10. The launches carry batches of older-design satellites into orbits that are part of the Starlink second-generation, or Gen2, constellation, which will ultimately be primarily populated by Starlink V2 Mini satellites and a larger spacecraft platform called Starlink V2 sized to launch on SpaceX’s enormous future Super Heavy booster and Starship rocket.

The Starship has nearly 10 times the payload lift capability of a Falcon 9 rocket, with greater volume for satellites, too.

According to Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist and expert tracker of spaceflight activity, SpaceX has launched 4,161 Starlink satellites to date, and 3,858 of the spacecraft are currently in orbit, including the 56 new satellites deployed Friday. The rest were prototypes, failed spacecraft, or satellites intentionally commanded to re-enter the atmosphere and burn up.

McDowell said it wasn’t surprising that SpaceX encountered difficulties activating the new Starlink V2 Mini satellites.

“You’re launching a new design of satellite,” he said. “It is really not uncommon for the early weeks of flying a new satellite to discover, ‘Oh, we’ve got some teething problems, we’ve got to debug some stuff before we can really commission the satellite.'”

Another change on the upgraded Starlink V2 Mini satellite design is in the propulsion system. The new satellites are propelled by an argon-fueled electric thruster system, capable of producing 2.4 times the thrust with 1.5 times the specific impulse, or fuel efficiency, of the krypton-fueled ion thrusters on the first generation of Starlink satellites.

Each Starlink V2 Mini satellite weighs about 1,760 pounds (800 kilograms) at launch, nearly three times heavier than the older Starlink satellites. The are also bigger in size, with a spacecraft body more than 13 feet (4.1 meters) wide, filling more of the Falcon 9 rocket’s payload fairing during launch, according to regulatory filings with the Federal Communications Commission.

The larger, heavier satellite platform means a Falcon 9 rocket can only launch about 21 Starlink V2 Mini payloads at a time, compared to more than 50 Starlink V1.5s on a single Falcon 9 launch.

“The V2 Minis, they’re not a completely clean sheet design from V1.5, but there’s a lot of new stuff on them, so we shouldn’t be too surprised that they’ve got some teething problems,” McDowell said.

This 10X time-lapse replay shows SpaceX’s Falcon 9 booster soaring high above the Atlantic Ocean near the Bahamas after blasting off from Cape Canaveral today.

The 15-story-tall reusable booster landed on a drone ship to wrap up its 10th flight to space.https://t.co/biik6N2uq6 pic.twitter.com/80f0Pg9Rge

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) March 24, 2023

The Starlink V2 satellites will be capable of transmitting signals directly to cell phones, a step forward in connectivity from space that other companies are also pursuing. The V2 Mini satellites introduce E-band for backhaul links with gateway stations.

“This means Starlink can provide more bandwidth with increased reliability and connect millions of more people around the world with high-speed internet,” SpaceX said before the first launch of Starlink V2 Mini satellites last month.

The two deployable solar panels on each Starlink V2 Mini satellite span about 100 feet (30 meters) tip-to-tip. The previous generation of Starlink V1.5 satellites each have a single solar array wing, with each spacecraft measuring about 36 feet (11 meters) end-to-end once the solar panel is extended.

The enhancements give the Starlink V2 Mini satellites a total surface area of 1,248 square feet, or 116 square meters, more than four times that of a Starlink V1.5 satellite.

The FCC granted SpaceX approval Dec. 1 to launch up to 7,500 of its planned 29,988-spacecraft Starlink Gen2 constellation, which will spread out into slightly different orbits than the original Starlink fleet. The regulatory agency deferred a decision on the remaining satellites SpaceX proposed for Gen2.

SpaceX began launching older-generation Starlink V1.5 satellites into the Gen2 constellation on Dec. 28.

The FCC previously authorized SpaceX to launch and operate roughly 4,400 first-generation Ka-band and Ku-band Starlink spacecraft that SpaceX has been launching since 2019.

The Gen2 satellites could improve Starlink coverage over lower latitude regions, and help alleviate pressure on the network from growing consumer uptake. SpaceX says the network has more than 1 million active subscribers, mostly households in areas where conventional fiber connectivity is unavailable, unreliable, or expensive.

The Starlink spacecraft beam broadband internet signals to consumers around the world, connectivity that is now available on all seven continents.

Jonathan Hofeller, SpaceX’s vice president of Starlink commercial sales, said earlier this month the company is producing about six satellites per day at a Starlink factory near Seattle.

The launch Friday was the 20th mission of the year for SpaceX, putting the company on a pace for approximately 88 Falcon rocket flights in 2023. The company started the year aiming to launch 100 Falcon rockets, not counting the planned debut of the much larger Starship rocket.

Aside from the Starlink mission next week from Cape Canaveral, SpaceX is gearing up to launch a Falcon 9 rocket Thursday from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California with a cluster of small satellites for the U.S. military’s Space Development Agency.

Up to six Falcon 9 rockets and one Falcon Heavy rocket — made by combining three Falcon 9 first stage cores together — are on SpaceX’s launch schedule in April.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.