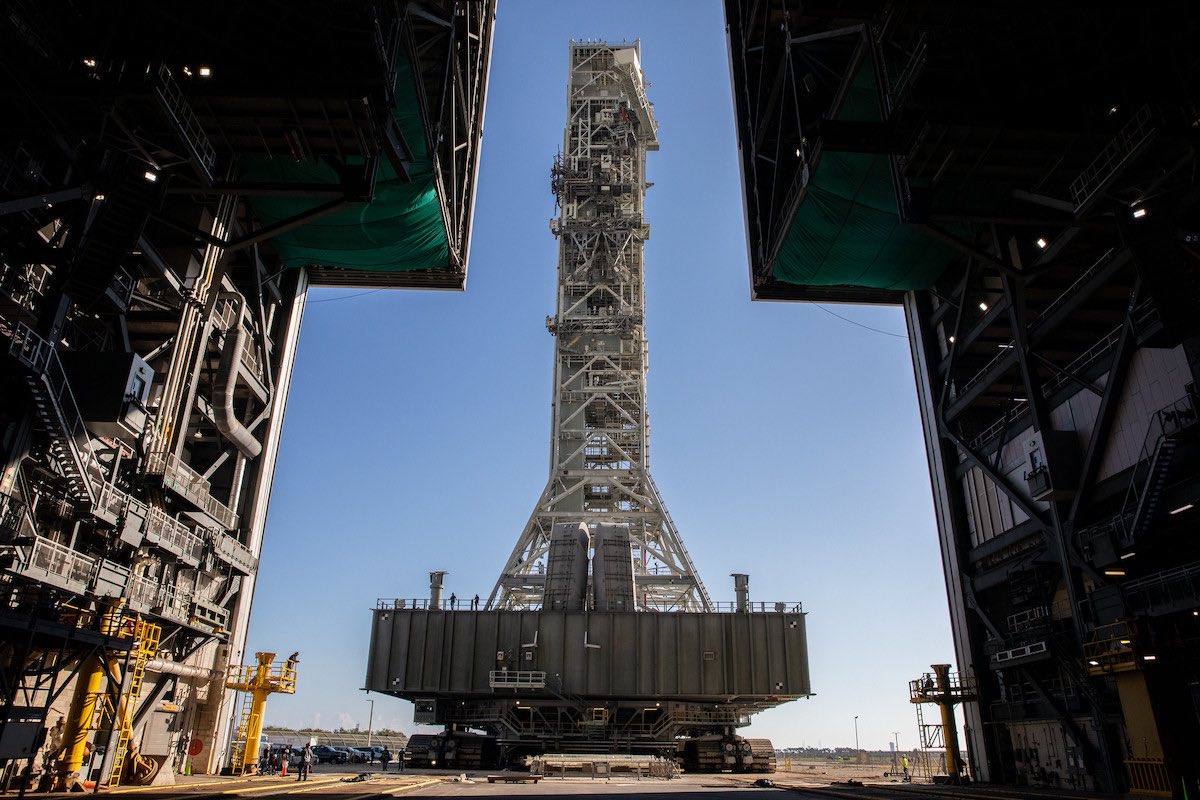

The mobile launch platform for NASA’s Space Launch System moon rocket rolled back into the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center Friday for inspections and repairs after liftoff of the Artemis 1 moon mission last month, setting the stage for upgrades to the 380-foot-tall structure before the first crewed Artemis moon flight scheduled for 2024.

NASA’s Artemis 2 mission will carry three U.S. astronauts and one Canadian on a loop around the back side of the moon, a 10-day test-flight that will send humans farther from Earth than ever before. Additional Artemis mission later in the 2020s will target landings on the moon’s surface and build an outpost called the Gateway in lunar orbit.

The Artemis 1 test flight launched Nov. 16 from pad 39B at Kennedy Space Center, sending NASA’s unpiloted Orion crew capsule on a path toward the moon aboard the first SLS moon rocket, a giant 322-foot-tall (98-meter) vehicle developed to propel astronauts into deep space. The Orion spacecraft reached the moon Nov. 21 and entered a distant orbit, then whipped by the moon again Dec. 5 to head for splashdown Sunday in the Pacific Ocean.

While the Artemis 1 mission has, so far, been a big success for NASA, ground crews at Kennedy are already starting preparations for Artemis 2.

Inspections of the SLS Mobile Launcher after liftoff of Artemis 1 last month showed relatively minor damage to the platform and its tower, which stands some 380 feet (115 meters) off the ground. Most of the damage was predicted, but teams discovered the blast of the rocket’s 8.8 million pounds of thrust blew the doors off elevators that run up and down the structure. That wasn’t expected, and caused it to take somewhat longer for technicians to complete their initial evaluation of the Mobile Launcher’s condition after the Nov. 16 blastoff.

Mike Sarafin, NASA’s Artemis 1 mission manager, said in a press conference that the steel structure of the Mobile Launcher weathered the rocket’s fury well. There was some expected damage to “soft goods” — like seals, gaskets, and hoses — on the umbilical arms that disconnected from the rocket at liftoff. But the umbilical arms themselves also held up during the launch.

“We did anticipate some amount of damage, and they are finding some amount of damage,” Sarafin said.

Vast volumes of water flowed onto the deck of the Mobile Launcher platform during engine ignition and liftoff, dampening the sound energy and overpressure as the rocket’s powerful solid rocket boosters fired off to send the vehicle off of the pad.

With inspections complete at the pad, ground teams at Kennedy moved the diesel-powered crawler-transporter underneath the Mobile Launcher earlier this week and began moving it off of pad 39B Thursday morning for the 4.2-mile (6.8-kilometer) journey to the Vehicle Assembly Building, where crews stacked the SLS moon rocket before the Artemis 1 launch.

The crawler parked outside the doors of the VAB on Thursday afternoon, then rolled into High Bay 3 inside the cavernous hangar Friday.

Contractor teams inside the VAB will spend a few weeks inspecting and repairing damage to the Mobile Launcher, then the crawler will move the structure to a park site north of the assembly building in January to start upgrades needed for Artemis 2.

One of the most signifiant upgrades will be the addition of an egress system that would whisk astronauts away from the launch pad in pre-launch emergency. Technicians will install pre-fabricated platforms some 300 feet up the Mobile Launcher tower. The platforms will support four baskets designed to slide down cables to reach ground level at the pad perimeter.

The emergency egress system for the Artemis launches is similar to the slidewire baskets used on the space shuttle program. SpaceX also has a similar egress system at pad 39A for astronaut launches on the Falcon 9 rocket and Crew Dragon spacecraft, and United Launch Alliance has a zipline-like system to quickly get astronauts off the pad during launches of Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule.

“One of the big things we’re doing from a ground systems standpoint is we’re adding crew emergency egress on the Mobile Launcher,” said Jeremy Parsons, deputy manager of NASA’s exploration ground systems program at Kennedy. “At the park site, what we’re going to do is we’re adding a series of a platform for emergency egress,” Parsons said.

“We already have all the major items fabricated, and we’re waiting on the Mobile Launcher to show up to begin work,” Parsons said. “So we’re feeling pretty good there.”

The cables that connect the Mobile Launcher’s egress platforms to the ground will be lifted onto the tower after it arrives at the launch pad, then hoists will raise the four slidewire baskets onto the tower in the run-up to launch day.

Another modification to the Mobile Launcher involves a change to the sound suppression and ignition overpressure water system. Technicians put in new water nozzles to change how the water flows onto the launch platform.

After teams finish work at the park site, the crawler will move the 11 million-pound Mobile Launcher back to pad 39B for verification and validation testing of the new emergency egress system and the new sound suppression water nozzles. The activities at the pad, scheduled for later in 2023, will include the hoisting of the slidewire cables and baskets onto the Mobile Launcher tower, and sound suppression water flow tests.

When the Mobile Launcher is back at pad 39B, ground teams will also run tests with a new 1.4 million-gallon liquid hydrogen storage tank at the seaside launch complex. The new liquid hydrogen tank adds to the fuel storage capacity at the pad to enable more launch opportunities for the Artemis 2 mission and future Artemis flights.

The space shuttle-era liquid hydrogen tank at the pad only contained enough fuel to support one SLS launch attempt. Tanker trucks needed to replenish the hydrogen tank after each fueling of the rocket, meaning Artemis 1 launch attempts had to be at least two days apart.

“We built a new hydrogen sphere that’s got over 1.4 million gallons,” Parsons said. “That will allow us to get more back-to-back launch attempts, which is a huge capability when we’ve got smaller (launch) windows and things like that.”

During an SLS countdown, super-cold liquid hydrogen flows from the ground storage tank through cross-country transfer lines and through the base of the Mobile Launcher, then into the core stage tank through a tail service mast umbilical. NASA found the hydrogen umbilical connection was leaky during the Artemis 1 launch campaign, but the launch team adjusted the loading procedure to reduce pressure on the umbilical seal. The changes eliminated any unsafe hydrogen leaks during the Artemis 1 launch countdown Nov. 16.

Validation testing with the new liquid hydrogen storage tank and the Mobile Launcher will help engineers “make sure we’re getting the right pressures, flow rates, no issues with manifolding, and things along those lines,” Parsons said.

“And then really a big piece of it will be testing our emergency egress system, making sure we’re hitting all of the expected loads onto that system, and then really kind of figuring out also how long that takes to set up, so we can plan our pad flows appropriately,” Parsons said.

There also be swing tests of the crew access arm on the Mobile Launcher to ensure it can move at faster speeds, which could be required in the event of a launch pad emergency with astronauts on the Orion crew capsule. The crew access arm is the walkway that astronauts and ground teams use to board the Orion spacecraft.

Then the Mobile Launcher will roll back to the Vehicle Assembly Building for more verification and validating tests before stacking of the Space Launch System for Artemis 2 gets underway.

Assembly the SLS moon rocket will begin with stacking of the two solid rocket boosters. The five pre-fueled segments of each booster will be delivered to Kennedy next year on railcars from Northrop Grumman’s booster factory in Utah.

Then the core stage will be positioned between the boosters. Boeing, the SLS core stage contractor, is finishing work on the Artemis 2 core stage at a factory in New Orleans before shipping the rocket to the Florida launch base. An upper stage and Orion crew capsule will be lifted on top of the core stage to finish the build-up of the Artemis 2 moon rocket before its launch set for 2024.

The Artemis 2 mission will use the same version of the Space Launch System, called Block 1, as Artemis 1. The Artemis 3 mission, scheduled for no earlier than 2025, will mark the first lunar landing of the Artemis moon program, and will be the final flight of the SLS Block 1 rocket configuration.

NASA and Boeing are developing a larger four-engine Exploration Upper Stage to replace the single-engine upper stage used on the SLS Block 1 rocket. The new Space Launch System configuration, called Block 1B, is taller and will need a new Mobile Launcher for the Artemis 4 mission.

Bechtel won a NASA contract to build the new Mobile Launcher, called ML-2, in 2019, but the project has suffered delays and cost overruns. A report by NASA’s inspector general in June blamed Bechtel for most of the problems with the ML-2 project. The inspector general reported Bechtel underestimated the overall scope and complexity of designing and building ML-2.

In a Senate hearing in May, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said Bechtel underbid on the ML-2 contract. Instead of costing $383 million, as originally projected, Bechtel estimates ML-2 is now expected to run $960 million before its completion in late 2025, according to NASA’s inspector general. But independent reviewers have concluded ML-2 could cost nearly $1.5 billion and may not be ready until late 2027.

Parsons said the readiness of ML-2, and not the development of the new upper stage, is currently in the critical path for the Artemis 4 launch. He said Bechtel is completing the design of the new Mobile Launcher, with steel fabrication due to begin in 2023.

“In terms of when we deliver (ML-2), we’re post-2025 right now,” he said. “Right now Mobile Launcher 2 is the critical path for Artemis 4. That’s something that we’re working the schedule very intensively on, adding shifts, looking at what we can compress, and things along those lines.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.