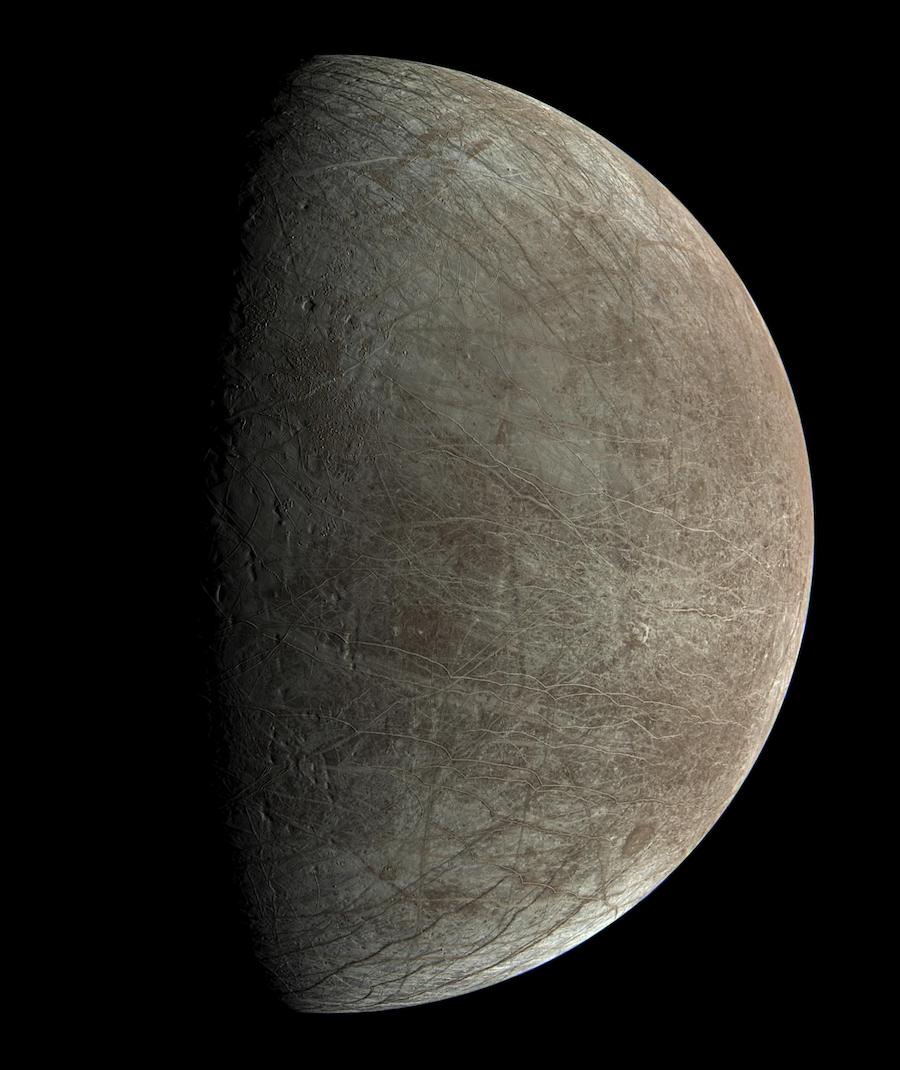

Continuing to gather bonus science data in an extended mission around Jupiter, NASA’s Juno spacecraft recorded sharp views of the icy moon Europa Sept. 29 as the solar-powered probe raced by at a relative velocity of nearly 53,000 mph (85,000 kilometers per hour).

Juno’s flyby of Europa was the closest visit of a spacecraft to Europa since Jan. 3, 2000, when NASA’s Galileo spacecraft flew 218 miles (351 kilometers) from the moon’s icy surface. Juno’s flyby Sept. 29 reached a distance of 218 miles from Europa.

Europa, slightly smaller than Earth’s moon, is covered in a global ice shell on top of an ocean of salty water that may be habitable. NASA is building the Europa Clipper spacecraft for launch in 2024 on a mission dedicated to studying Jupiter’s icy moon, and to search for evidence that Europa harbors the ingredients for life.

Europa Clipper will make nearly 50 flybys of Europa after reaching Jupiter in 2030, traveling as close as 16 miles (25 kilometers) from Europa’s frozen crust. But the Juno spacecraft had just two hours to capture data Sept. 29.

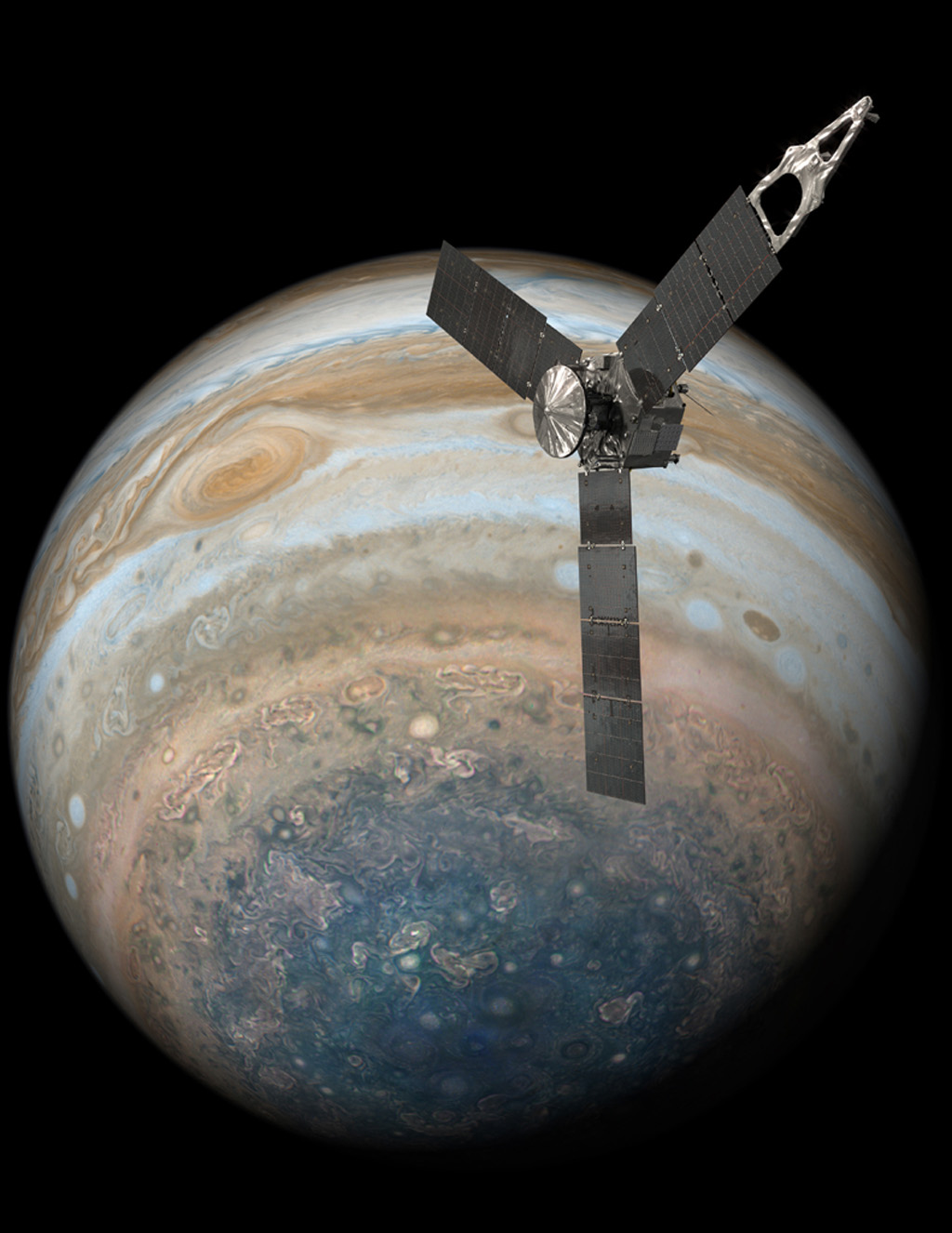

Juno was designed to collect data on Jupiter itself, focusing its science instruments on the giant planet’s atmosphere, magnetic field, and internal structure. Juno was also the first spacecraft to image the poles of Jupiter after entering orbit around the planet on July 4, 2016. The robotic mission launched Aug. 5, 2011, from Cape Canaveral aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket.

NASA approved an extension of the Juno mission in early 2021, allowing the spacecraft — if it remains healthy — to continue its exploration around the solar system’s largest planet through September 2025.

Jupiter’s asymmetric gravity field is gradually perturbing Juno’s trajectory and pulling the closest point of the spacecraft’s elongated orbit northward over time. The shift in Juno’s orbit will allow the spacecraft to get a better view of Jupiter’s North Pole, and also enables flybys of Ganymede, Europa, and Io, three of the planet’s largest moons.

Juno flew by Ganymede on June 7, 2021, and is on track for two encounters with the volcanic moon Io on Dec. 30, 2023, and Feb. 3, 2024.

The spacecraft’s orbit is growing shorter with each flyby. The pull of gravity from Ganymede shortened Juno’s orbit from 53 to 43 days last year, and Europa’s gravity tightened Juno’s orbital period around Jupiter to 38 days. The Io flybys in 2023 and 2024 will pull the Juno spacecraft into a smaller orbit with a period of 33 days.

“Juno started out completely focused on Jupiter,” said Scott Bolton, Juno’s principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “The team is really excited that during our extended mission, we expanded our investigation to include three of the four Galilean satellites and Jupiter’s rings.

“With this flyby of Europa, Juno has now seen close-ups of two of the most interesting moons of Jupiter, and their ice shell crusts look very different from each other. In 2023, Io, the most volcanic body in the solar system, will join the club,” Bolton said in a statement.

Juno’s nine scientific instruments include a microwave radiometer for atmospheric soundings, ultraviolet and infrared spectrometers, particle detectors, a magnetometer, and a radio and plasma waves experiment. The Jupiter orbiter also carries a color camera known as JunoCam, which collects image data for processing and analysis by an army of citizen scientists around the world.

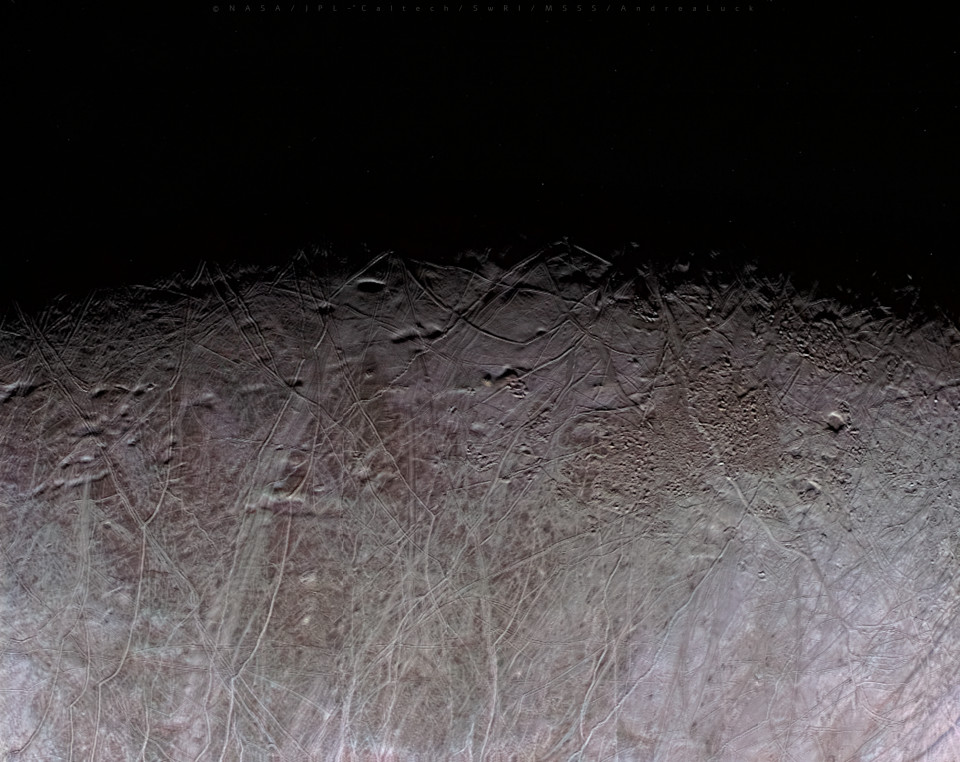

JunoCam captured images of Europa doing the Sept. 29 flyby, while the spacecraft’s other instruments were tuned to look for particles lofted from Europa in possible eruptions through fractures in the moon’s global ice sheet. Signs of recurring eruptions from Europa were detected by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Juno’s microwave radiometer was expected to probe the thickness of Europa’s global ice shell. And the spacecraft’s spectrometers were to map concentrations of water ice, carbon dioxide and organic molecules across about 40 percent of Europa’s surface.

“The science team will be comparing the full set of images obtained by Juno with images from previous missions, looking to see if Europa’s surface features have changed over the past two decades,” said Candy Hansen, a Juno co-investigator who leads planning for the JunoCam camera at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona. “The JunoCam images will fill in the current geologic map, replacing existing low-resolution coverage of the area.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.