South Korea’s first moon orbiter launched Thursday from Cape Canaveral on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, heading off on a mission to survey potential lunar landing sites and search for water ice hidden inside shadowed craters near the moon’s poles.

The Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter, or KPLO, spacecraft launched on top of a Falcon 9 rocket at 7:08:48 p.m. EDT (2308:48 GMT) Thursday from pad 40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida.

The launch of the KPLO mission occurred 12 hours and 39 minutes after an Atlas 5 rocket from SpaceX rival United Launch Alliance departed a separate launch pad at Cape Canaveral with a U.S. military missile warning satellite.

The last time there was such a short span between two orbital-class rockets lifting off from Cape Canaveral was on Sept. 7 and 8, 1967, when a Thor Delta G rocket and an Atlas Centaur rocket launched less than 10 hours apart. The Thor Delta G rocket launched a recoverable spacecraft called Biosatellite 2 with a host of biological research experiments, and the Atlas Centaur sent NASA’s Surveyor 5 lander to the moon.

A moon mission made up the second half of Thursday’s doubleheader, too.

The KPLO mission is a pathfinder, or precursor, for South Korea’s future ambitions in space exploration, which include a robotic landing on the moon in the early 2030s. South Korea has also signed up to join the NASA-led Artemis Accords, and could contribute to the U.S. space agency’s human lunar exploration program.

The KPLO mission is also named Danuri, a combination of the words “dal” and “nurida” in Korean, meaning “enjoy the moon.”

“The basic idea of this mission is technological development and demonstration,” said Eunhyeuk Kim, the mission’s project scientist from the Korea Aerospace Research Institute, or KARI. “Also, using the science instruments, we are hoping to get some useful data on the lunar surface.”

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket deployed the 1,495-pound (678-kilogram) KPLO spacecraft about 40 minutes after liftoff, after using two burns of its upper stage engine to accelerate the probe on a trajectory to take it beyond the moon. The Falcon 9’s first stage booster, flying for the sixth time, aced its landing on a drone ship holding position in the Atlantic Ocean east of Cape Canaveral.

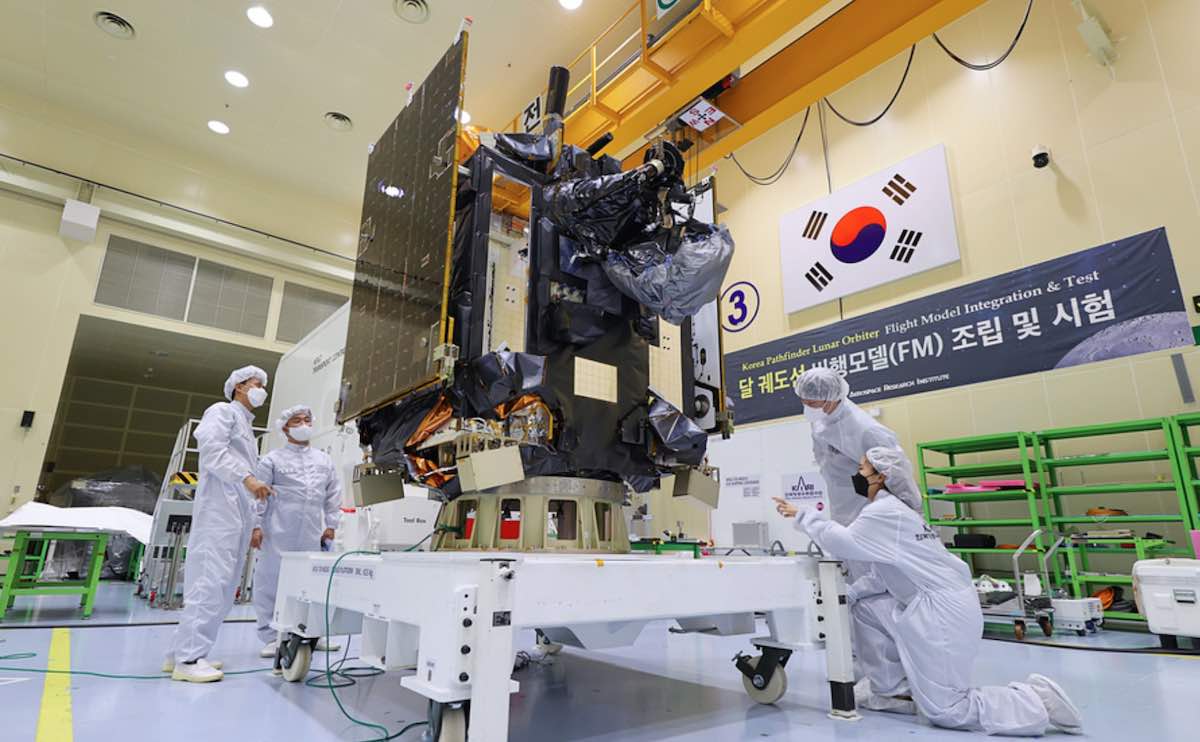

Ground controllers at KARI, South Korea’s space agency, received the first signals from the spacecraft through a ground station around 92 minutes after liftoff. The spacecraft extended its power-generating solar panels, with a wingspan of more than 20 feet (6.3 meters), and engineers confirmed the probe was “operating normally.”

The KPLO mission carries six science instruments and technology demonstration payloads.

KPLO will test a new South Korean spacecraft platform designed for deep space operations, along with new communication, control, and navigation capabilities, including the validation of an “interplanetary internet” connection using a disruption tolerant network.

The launch of the KPLO mission, or Danuri, comes less than two months after South Korea successfully flew its first all-domestic launcher into low Earth orbit. The South Korean rocket, called the Nuri, successfully launched on its orbital test flight June 21.

“The Danuri is the first lunar orbiter that Korea has built, and along with the development of the Nuri, it will be possible to raise Korea’s international status in the space field and provide an opportunity to take off as a space power,” said Oh Tae-Seog, South Korea’s vice minister of science, information, and communications technology.

“The technology acquired through the development of Nuri and the scientific data obtained through the operation of the mission of Danuri are expected to greatly contribute to lunar science research in Korea in the future, as well as raise public interest in space development,” he said.

The mission’s scientific objectives include mapping the lunar surface to help select future landing sites, surveying resources like water ice on the moon, and probing the radiation environment near the moon.

KPLO cost about $180 million to develop, according to KARI. The Falcon 9 rocket launched the KPLO spacecraft toward the moon on a low-energy, fuel-efficient ballistic lunar transfer trajectory, a path being pioneered by NASA’s small CAPSTONE spacecraft, a tech demo mission that launched in June on a Rocket Lab mission and is scheduled to slip into orbit around the moon in November.

Instead of reaching the moon in a few days, like NASA’s Apollo missions, KPLO will take about four months to complete the journey.

KPLO’s arrival date at the moon is fixed on Dec. 16. The Falcon 9 propelled the spacecraft on a trajectory that will take it close to the L1 Lagrange point, a gravitationally-stable location nearly a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from the daytime side of the Earth, some four times farther than the moon.

A course correction burn is scheduled for Sept. 2 on the spacecraft’s outbound journey from Earth.

Gravitational forces will naturally pull the spacecraft back toward the Earth and the moon, where the Korean probe will be captured in orbit Dec. 16. A series of propulsive maneuvers with the spacecraft’s thrusters will steer KPLO into a circular low-altitude orbit about 60 miles (100 kilometers) from the lunar surface by New Year’s Eve.

After a month of commissioning and tests, the spacecraft’s year-long primary science mission should begin around Feb. 1. If the orbiter has enough fuel, mission managers could consider an extended mission beginning in 2024, Kim said.

One of the payloads on the KPLO, or Danuri, mission is a U.S.-built instrument named ShadowCam.

Derived from the main camera on NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, ShadowCam will peer inside dark craters near the moon’s poles, where previous missions detected evidence of water ice deposits. The NASA-funded ShadowCam instrument is hundreds of times more sensitive than LRO’s camera, allowing it to collect high-resolution, high signal-to-noise imagery of the insides of always-dark craters using reflected light.

Prasun Mahanti, the deputy principal investigator for the ShadowCam instrument at Arizona State University, said the camera will help scientists understand the unexplored depths of the permanently shadowed craters in the lunar poles, “regions that never receive direct sunlight and often are extremely cold.”

NASA is also providing tracking and communications support for the KPLO mission through its Deep Space Network antennas in California, Spain, and Australia. KARI, South Korea’s space agency, also has its own deep space communications antenna, but it doesn’t offer the continuous coverage of NASA’s worldwide network.

South Korea began developing the KPLO mission in 2016 for a planned launch in 2020, but officials delayed the mission after the spacecraft grew above its original launch weight, and engineers needed more time to complete detailed design work.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.