NASA has awarded Draper a $73 million contract to deliver science instruments to the far side of the moon on a commercial robotic lander in 2025, the eighth award through the agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program. Officials with the companies flying the first two CLPS missions, Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines, said recently their commercial landers are scheduled to launch late this year or early next year.

The CLPS program is intended to foster development of commercial capabilities to land on the moon, delivering science instruments and cargo in support of NASA’s Artemis program. The first seven CLPS mission task orders awarded by NASA are for landings on the near side of the moon or near the moon’s south pole, where the agency plans to send astronauts on human landing missions.

Draper is one of 14 companies eligible to receive individual mission contracts, or task orders, through NASA’s CLPS program. The task order awarded July 21 was the first received by Draper since NASA selected the first batch of CLPS contractors in 2018 to complete for moon missions.

Draper’s contract with NASA, valued at $73 million, covers the entire mission to the far side of the moon. As prime contractor, Draper is responsible for developing the lander system and procuring a launcher to send the spacecraft from Earth to the moon.

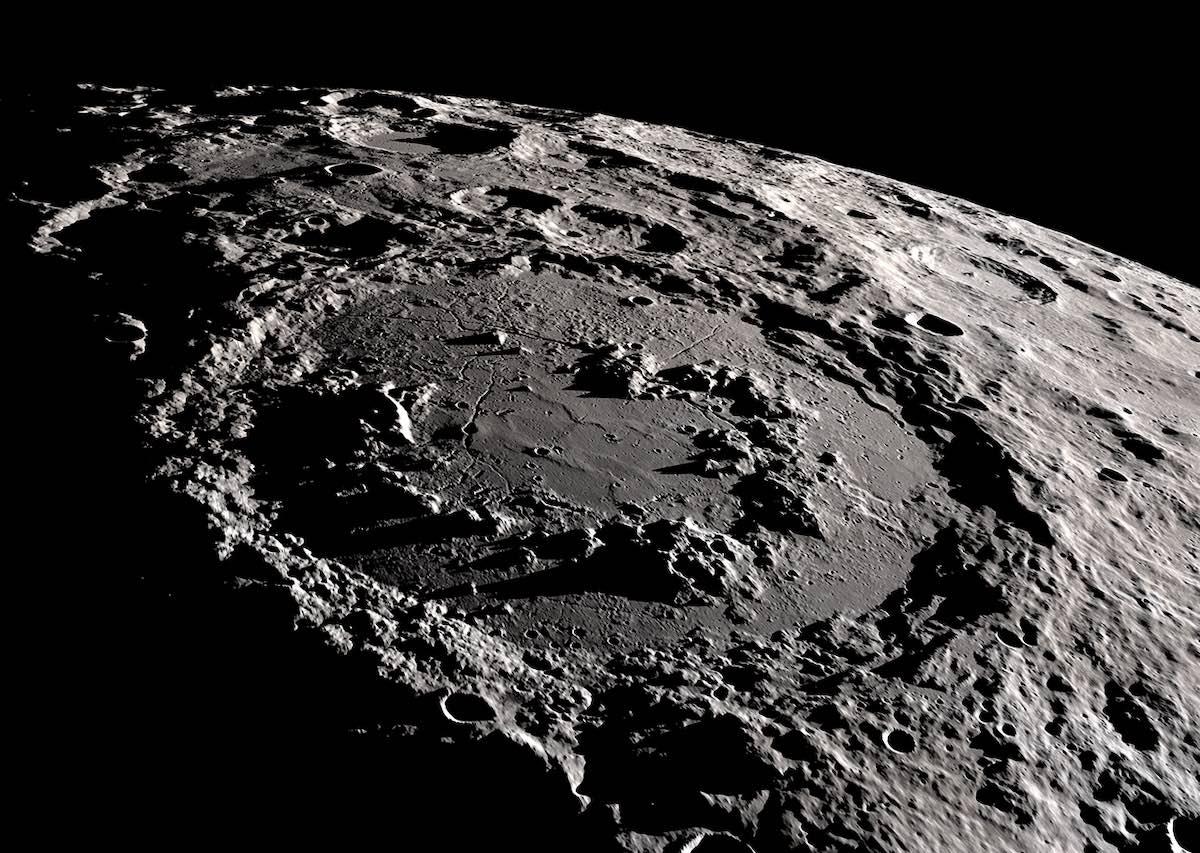

The SERIES-2 lander managed by Draper will attempt to land in Schrödinger Basin, a 200-mile-wide (320-kilometer) impact crater on the far side of the moon near the south pole. The only soft landing on the back side of the moon to date has been China’s Chang’e 4 mission, a robotic lander and rover that touched down on the lunar surface in January 2019.

“This lunar surface delivery to a geographic region on the moon that is not visible from Earth will allow science to be conducted at a location of interest but far from the first Artemis human landing missions,” said Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration in NASA’s science mission directorate. “Understanding geophysical activity on the far side of the moon will give us a deeper understanding of our solar system and provide information to help us prepare for Artemis astronaut missions to the lunar surface.”

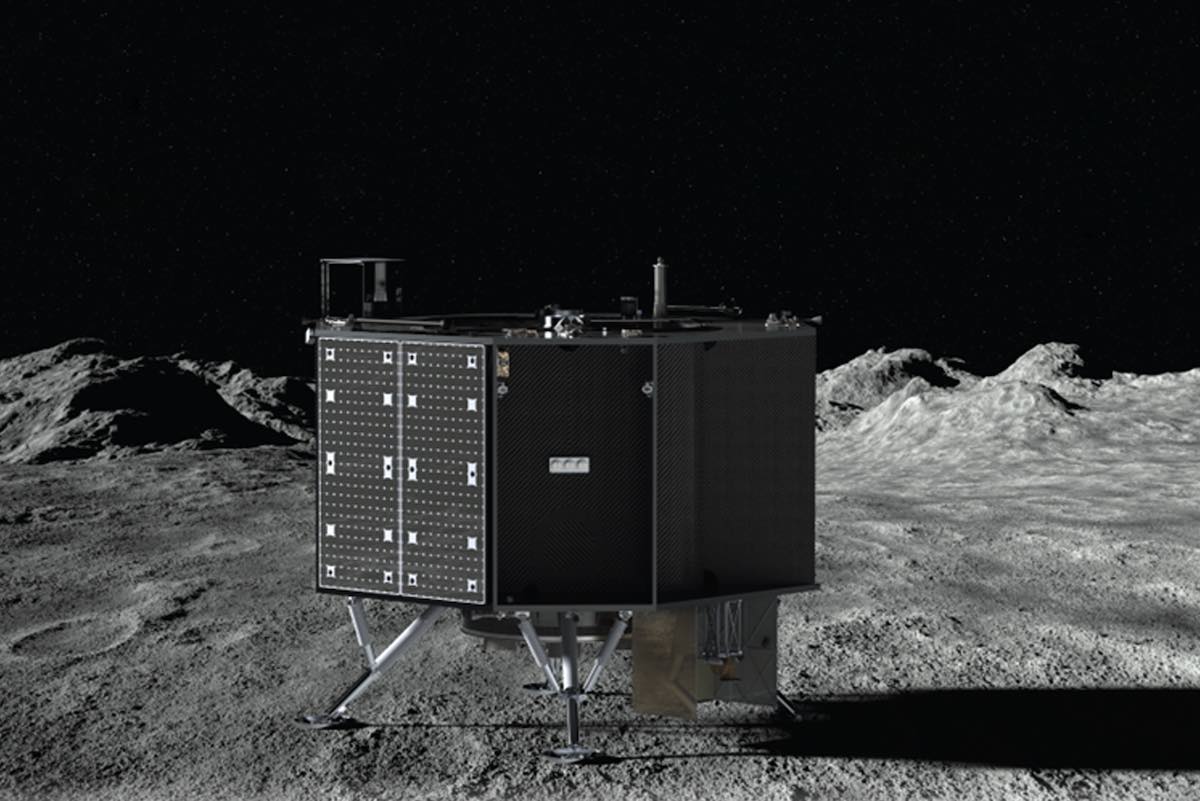

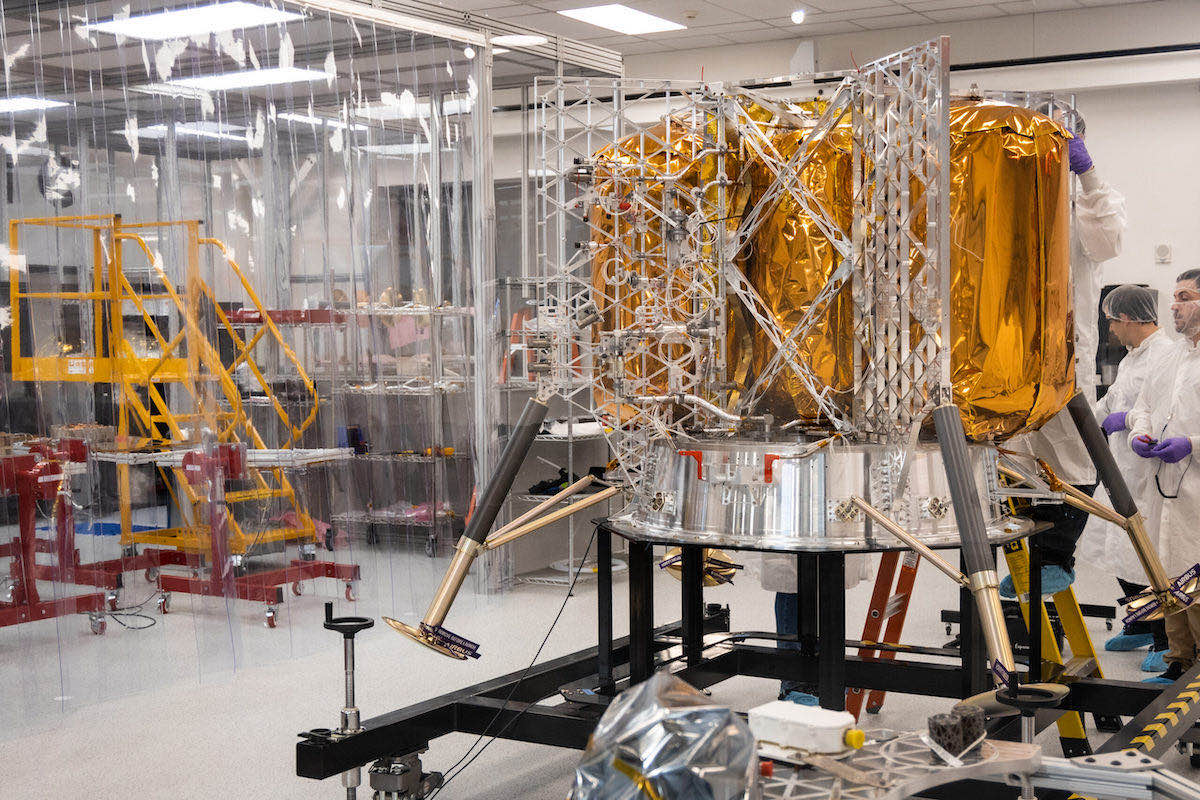

Draper is partnering with a company named ispace to design the SERIES-2 lander. Headquartered in Japan, ispace owns a U.S.-based division to build the SERIES-2 lander, which will stand about 11.5 fee (3.5 meters) tall and measure around 14 feet (4.2 meters) wide, including its landing legs.

Systima Technologies, a division of Karman Space and Defense, will lead manufacturing, assembly, integration, and testing of the lander. And General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems will integrate the mission’s scientific payloads. Draper, which developed guidance computers for NASA’s Apollo lunar program, said in a statement it will provide the descent guidance, navigation, and control system for the SERIES-2 lander, plus overall program management, systems engineering, integration and test services, and mission and quality assurance.

“Draper and its teammates are honored to be selected by NASA to deliver these important payloads to the lunar surface, paving the way for human and robotic exploration missions to follow. With our heritage in space exploration, originating with the Apollo program, and our deep roots and broad technology presence in the space sector, Draper is poised to ensure U.S. preeminence in the commercialization of cislunar space,” said Pete Paceley, Draper’s principal director of civil and commercial space systems.

In response to a question from Spaceflight Now, Paceley said Draper has decided on a launch provider for the CLPS mission, but needs to finish paperwork on the deal before announcing it publicly.

Schrödinger Basin is one of the youngest impact basins on the lunar surface with evidence of volcanic activity in the recent geological past. The impact that created the crater uplifted material from the deep crust and upper mantle of the moon, and the location was the site of a large volcanic eruption, according to NASA.

Draper’s lander will deliver three NASA-funded science instruments to the moon with a combined mass of about 209 pounds (65 kilograms). The payloads will collect NASA’s first seismic data from the far side of the moon, drill into the lunar crust to measure subsurface heat, measure the electrical conductivity of the moon’s interior, gather information on the magnetic field at the landing site, and study surface weathering.

Because the far side of the moon is hidden from Earth-based antennas, Draper’s industry team will dispatch two data relay satellites built by Blue Canyon Technologies to an orbit near the moon to link ground controllers and scientists with the lander on the lunar surface.

NASA’s first two CLPS missions are scheduled for launch late this year or early next year, industry officials said.

Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines won the first batch of CLPS task orders in May 2019, when the companies said they planned to land on the moon in 2021. Astrobotic’s Peregrine lander is now scheduled to launch at “the end of the year,” said Dan Hendrickson, Astrobotic’s vice president of business development, in a July 20 panel discussion at the NASA Exploration Science Forum.

Timothy Crain, chief technology officer at Intuitive Machines, said the company’s first mission its Nova-C lander is expected to be delayed from late this year into January. Astrobotic’s lander will launch on the inaugural flight of United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket, while Intuitive Machines will launch its mission on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

NASA has awarded three CLPS missions to Intuitive Machines, two to Astrobotic, one to Masten Space Systems, one to Firefly Aerospace, and now has issued one task order to Draper.

NASA and industry officials have emphasized the high-risk, high-reward nature of the CLPS program. Many of the companies in NASA’s CLPS contractor pool have little experience in spacecraft development or operations, and NASA officials have said some of the landings could fail.

Asked about his concerns about the future of the CLPS program, Shea Ferring, a vice president at Firefly, identified NASA’s resilience to failures.

“Are they going to stick with it if the first few missions have problems within the first year?” Ferring said. “This is going to be easy three to five years from now, but until we get to that point, it’s not going to be easy, and we need NASA to stick with it and to be, effectively, our anchor customer.”

“I think the the basic tech to land a robotic lander on the surface of the moon and have it survive for 14 Earth days is there,” Hendrickson said. “But the challenge is in making sure that we steel ourselves as a nation to stomach when we do have a bad day.”

Hendrickson compared the CLPS program to NASA’s commercial cargo program, which contracted with SpaceX and Northrop Grumman to deliver supplies to the International Space Station. Both companies suffered launch failures early in the program.

“The Commercial Resupply Services program had a couple of those in dramatic fashion, and yet they stayed the course, and they kept pushing and kept flying, and now it just happens all the time on a regular basis,” Hendrickson said. “And I think the same will happen for the moon. here may be some challenges along the way, and we need to stay the source to make sure that we’re still progressing.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.