NASA’s powerful new Space Launch System moon rocket was hauled from its launch pad back to the Vehicle Assembly Building at the Kennedy Space Center Saturday for final repairs, testing and closeouts, moving closer to liftoff later this summer after completing a fueling demonstration last month.

The 322-foot-tall (98-meter) moon rocket rolled off its posts at pad 39B at 4:12 a.m. (0812 GMT) Saturday, about five hours behind schedule to allow time for extra inspections. A diesel-powered crawler-transporter carried the Space Launch System rocket down the ramp and along the rock-covered crawlerway on the 4.2-mile (6.8-kilometer) journey back to the Vehicle Assembly Building.

The launcher rolled into High Bay 3 of the iconic assembly hangar around 2 p.m. EDT (1800 GMT), and was secured inside the VAB about a half-hour later.

The return of the SLS moon rocket to the Vehicle Assembly Building moves the Artemis 1 mission a step closer to launch on a test flight around the moon. After a decade in development costing more than $20 billion, the Artemis 1 mission will mark the first flight of the huge SLS moon rocket, sending an Orion crew capsule on a course to orbit the moon.

The test flight will not carry astronauts, but will be the first launch of a human-rated rocket and spacecraft to the moon since the Apollo program. If the Artemis 1 flight goes according to plan, NASA intends for the next SLS/Orion mission — Artemis 2 — to carry a crew of around on a loop around the far side of the moon and back to Earth in 2024, marking the first astronaut voyage to the moon since 1972.

Future Artemis missions will incorporate a commercial crew lander to ferry astronauts between the Orion spacecraft in lunar orbit and the surface of the moon.

NASA’s launch team fully loaded the moon rocket with cryogenic liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants during a practice countdown June 20, accomplishing a major test objective managers wanted to complete before proceeding with final launch preps.

A series of practice countdown runs in April were plagued by technical problems that prevented the full fueling of the rocket.

The June 20 countdown rehearsal was not free of trouble. Engineers detected a hydrogen leak in a quick-disconnect fitting near the bottom of the rocket’s core stage, in a line that dumps excess hydrogen overboard from the system to thermally condition the four RS-25 main engines for ignition.

The launch team overcame the problem and continued the countdown to T-minus 29 seconds, about 20 seconds before the time engineers wanted to reach in the dress rehearsal. One of the final test objectives not accomplished June 20 was a hot-fire of hydraulic pumps powering the steering mechanisms on the rocket’s two solid-fueled boosters, which provide 80% of the steering control for the first two minutes of launch.

NASA ground teams successfully activated the hydraulic power units during a separate test June 25, paving the way for crews to prep the rocket for rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building.

The return to the rocket hangar was supposed to begin late Thursday, but NASA pushed back the move by a day to complete work on the slope of the crawler way leading to the launch pad. Teams completed grating, or sifting, the crawlerway using heavy equipment before going ahead with rollback Friday night.

The crawler reached a top speed of nearly 1 mph during the trip back to the VAB. The combined stack of the SLS moon rocket, its mobile launch platform, and the crawler vehicle weighs about 21.4 million pounds.

NASA’s ground team briefly stopped the crawler and the SLS moon rocket outside the VAB around midday Saturday, allowing time for the crew access arm on the mobile launcher tower to move into position next to the Orion crew capsule on top of the vehicle.

The access arm is retracted against the mobile launcher tower while it is in motion, and can’t be extended once the rocket is inside the assembly building.

With the arm extended, the crawler continued moving through the vertical door of High Bay 3. The transporter’s jacking and leveling system lowered the mobile launch platform onto pedestals inside the VAB to complete the journey from pad 39B.

The space agency has not formally set a target launch date for the first SLS moon rocket, but officials are aiming to have the launcher ready to blast off on the Artemis 1 test flight in late August or early September, when the alignment of the moon, the sun, and the Earth will enable the mission to meet all its objectives.

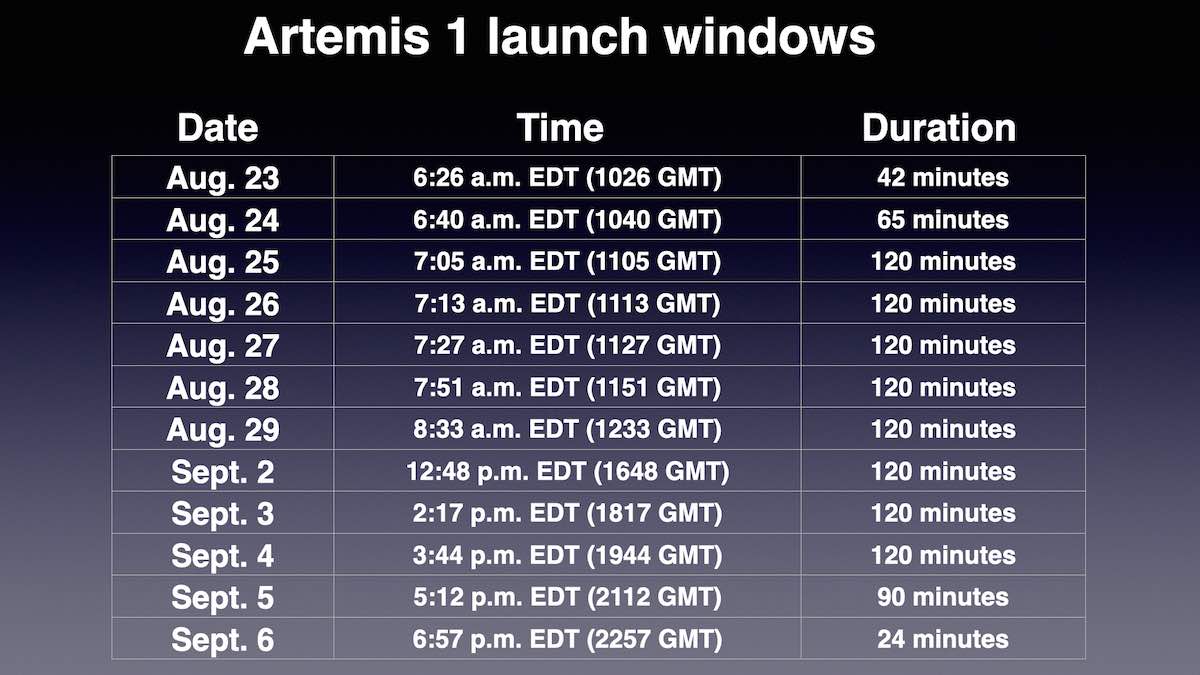

A launch period opens Aug. 23 and runs until Sept. 6. NASA has another launch period available beginning Sept. 19 and extending until Oct. 4, followed by three more two-week launch periods through the end of the year. Depending on when the Artemis 1 mission takes off, the Orion test flight could last roughly 26 days or as long as 42 day. The mission duration hinges on the location of the moon relative to Earth, allowing the Orion spacecraft to complete a half-orbit or one-and-a-half distant orbits around the moon.

The launch periods are constrained by a number of considerations, including the position of the moon in its orbit around Earth, limits on how long the Orion spacecraft can fly in shadow without direct sunlight on its solar arrays, and re-entry and splashdown rules, including a requirement for a daytime return to Earth to aid in recovery operations in the Pacific Ocean.

The launch windows for the Aug. 23-Sept. 6 window are posted below. Aug. 30, Aug. 31, and Sept. 1 not viable launch dates because not all of the launch window constraints are met for those days.

Once the rocket is back inside the assembly building, workers will extend 10 sets of access platforms to reach various levels of the launch vehicle, and erect an access stand to reach the leaky hydrogen line.

Aside from already-planned work to ready the rocket for launch, technicians will repair the leaky hydrogen connector discovered during the fueling demonstration last month. Workers will replace Teflon seals on quick-disconnect fittings in the tail service mast umbilical, the connection that routes cryogenic propellants between the mobile launch platform and the SLS core stage.

Officials believe one of those seals loosened in the 4-inch quick-disconnect that started leaking during the June 20 countdown rehearsal. Phil Weber, an integration manager on the Artemis ground operations team, said last week that workers will also likely change out a similar seal on a larger 8-inch propellant fill and drain line as a pre-emptive measure.

Other work inside the VAB will include changing out an avionics box on the SLS upper stage, and a software load on the upper stage computer. The ground crew will also stow final equipment inside the pressurized cabin on the Orion spacecraft, and install flight batteries on the core stage, boosters, and second stage, according to Cliff Lanham, the Artemis 1 flow director on NASA’s ground operations team at Kennedy.

“Then, ultimately, we want to do our flight termination system testing, and once that’s complete, we’ll be able to perform our final inspections on all the volumes of the vehicle and do our closeouts,” Lanham said in a June 24 press briefing.

The flight termination system consists of pyrotechnic charges on the rocket that would be fired to destroy the vehicle if it veered off course and threatened populated areas.

The ground crew inside the VAB will arm the flight termination system and perform an end-to-end test, demonstrating the ability of the Space Force’s range safety team to send a destruct command to the SLS moon rocket. The flight termination system is only certified for 20 days after completion of the test, and the rocket would need to be hauled back to the VAB to revalidate the destruct mechanisms.

According to Lanham, work on the SLS moon rocket inside the Vehicle Assembly Building will take about six to eight weeks.

Weber said the ground crew will be “hustling” to roll the rocket back to pad 39B after the flight termination system check. The rocket will need to spend 10 to 14 days on the pad before the first launch attempt, and the schedule currently shows the Artemis 1 team could fit in three launch attempts before the 20-day flight termination system certification clock expires.

NASA officials are expected to set a target launch date as soon as next week.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.