Russia’s decision to partner with China on a planned lunar research station, and not join the U.S.-led Artemis moon program, was disappointing after more than two decades of cooperation on the International Space Station, says NASA’s top human spaceflight official.

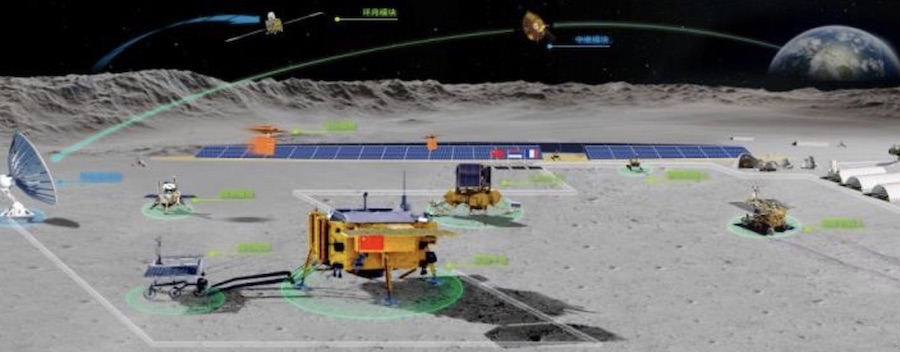

Russian and Chinese space officials signed a memorandum of understanding March 9 to partner on an International Lunar Research Station. The joint lunar program is “open to all interested countries and international partners,” the China National Administration said in a statement.

The concept pursued by China and Russia could include robotic and crewed elements on the moon’s surface, likely at the lunar south pole. The countries said the exploration program may also include a long-term science platform in orbit around the moon.

The International Lunar Research Station “will carry out multi-disciplinary and multi-objective scientific research activities such as the lunar exploration and utilization, lunar-based observation, basic scientific experiment and technical verification,” China’s space agency said.

Chinese and Russian officials said the countries will “jointly formulate a roadmap” for construction of the lunar research station, and closely collaborate on planning, demonstration, design, development, implementation, and operation of the outpost. They will also promote the project to “international space communities,” the space agencies said in a statement.

China has an advanced a lunar robotic exploration program. In 2019, China landed the first spacecraft on the far side of the moon, and the Chinese Chang’e 5 mission last year returned the first samples from the lunar surface since 1976, when Russian sent its last robotic mission to the moon.

Russia is developing a lander named Luna 25 that could launch to the moon before the end of this year, the first mission in a revival of Soviet-era Luna program. Two follow-up missions, Luna 26 and Luna 27, will orbit the moon and attempt a landing near the south pole. The Luna 27 lander, set for launch in 2025, will carry instruments from the European Space Agency, including a drill and a sophisticated mini-laboratory to analyze lunar soil in search of water ice.

European nations have agreed to fly experiments on Chinese lunar missions, too.

China’s next robotic lunar mission, Chang’e 6, is scheduled for launch in 2023 or 2024. Building on the Chang’e 5 mission last year, Chang’e 6’s objective will be to collect and return samples to Earth from a location near the moon’s south pole.

Around the same time, China plans to launch the Chang’e 7 mission, an ambitious multi-spacecraft expedition including a lunar orbiter, a lander, a rover, a “hopper” to fly across the lunar surface, and a communications relay satellite.

Before the end of the 2020s, China aims to launch another robotic mission named Chang’e 8 to a site near the lunar south pole. Chang’e 8 will test out technologies for in-space manufacturing and lunar resource harvesting that could be used by a crewed landing mission.

Chinese and Russian officials did not say last week when the International Lunar Research Station might be operational, but China has previously said it could be ready for crewed lunar landings in the 2030s.

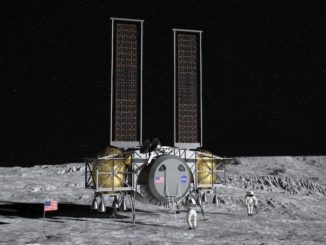

The International Lunar Research Station resembles NASA’s Artemis program, which will include an orbiting mini-space station near the moon called the Gateway, plus sustained crewed missions to the south pole of the moon. The goal of the Artemis program is to set up a permanent human presence at the moon and refine technologies needed for future voyages to Mars.

NASA has signed memorandums of understanding with ESA and the governments of Japan and Canada to work together on the Artemis missions. All are partners on the International Space Station in low Earth orbit, and will provide major elements of the Gateway space station.

“I think we were disappointed,” said Kathy Lueders, associate administrator for NASA’s human exploration and operations mission directorate. “I think the International Space Station has been really a great international collaboration, but one of our great partnerships has been with our Russian counterparts.”

The International Space Station is expected to remain operational through the late 2020s, when NASA hopes a commercial company will be ready with a privately-owned research outpost in low Earth orbit. If that happens, NASA and other government space agencies could buy access to the commercial space station for astronauts and science experiments, rather than operating the entire research complex.

Russia has “been a partner that’s done things very, very differently, and we’ve learned a ton from them,” Lueders said last month, when Russia announced its intention to partner with China. “We have honestly learned a ton. We tend to kind of be finesse engineers, and they just are robust … So we’ve learned from the partnership with them, and we were hoping to continue that partnership around the lunar surface.

“We understand now that they have different priorities, and currently they have said that this is not a partnership that is aligned with that they’re thinking. But I’m hoping, over time, we bind future partnerships.

“I feel very strongly that NASA is way for us … to be able to create ties that bind us through good times and bad times. So I hope to find some more ways to be able to help us bridge across nations and be able to work together in peaceful ways going forward,” Lueders said.

“The cooperation between NASA, Roscosmos, and other space agencies has been instrumental in the long-term success of the International Space Station,” said Monica Witt, a NASA spokesperson. “We are eager to extend the relationships and lessons learned from the ISS as we build the Gateway, which will form the cornerstone of sustainable lunar operations while demonstrating key technologies and processes for a historic human mission to Mars.

“While Roscosmos has informed NASA that it does not wish to be part of the Gateway partnership at this time, they did offer to continue exploring interoperability and we welcome such a discussion,” Witt said in a written statement.

NASA wanted Russia to build an airlock to support spacewalks by astronauts outside the Gateway. Witt said NASA still plans to add an airlock to the Gateway in 2028, and said the agency “will be pursuing other options for the provider of the airlock.”

The U.S. space agency has also established agreements known as the Artemis Accords, which set out principles for exploration and expectations for norms of behavior in space. The principles include peaceful exploration, transparency, interoperability, emergency assistance, the registration of artificial space objects, and public release of scientific data.

Early signatories of the Artemis Accords include the United States, Australia, Canada, Japan, Luxembourg, Italy, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, and the United Arab Emirates.

Russia has not signaled any intention to sign the accords. NASA is legally barred from bilateral partnerships with China in space exploration.

NASA plans to use a mix of launches using the agency’s new heavy-lift Space Launch System rocket, commercial rockets, the Orion crew capsule, and privately-developed, government-funded lunar landers for the Artemis missions.

Russia is NASA’s largest partner on the International Space Station, a partnership cemented in 1993 agreement after the end of the Cold War. But fractures between the two partners are growing as diplomatic relations have soured in recent years.

Last October, the head of Roscosmos — Russia’s space agency — said the Artemis program is “too U.S.-centric.”

“Our American partners are actively promoting it,” said Dmitry Rogozin, director general of Roscosmos, in a virtual International Astronautical Congress panel in October. “In our view, lunar Gateway, in its current form, is too U.S.-centric.”

“Russia is likely to refrain from participating in it on a large scale,” Rogozin said of the Gateway.

Rogozin said last year that Roscosmos wants to ensure its next-generation Orel crew spacecraft can dock with the Gateway. The Orel spacecraft is in development to replace Russia’s Soyuz crew capsule, and will be designed to carry astronauts into low Earth orbit and destinations beyond.

The Orel spacecraft “is designed for future national manned missions, and should the need arise, it can also be used for the benefit of our partners as a backup option to launch astronauts into space or bring them back from orbit,” Rogozin said.

China is also developing a next-generation crew capsule capable of bringing astronauts home from the moon.

“Talking about our program, it’s a national program, first and foremost. The United States, together with its partners, is pursuing its Artemis program,” Rogozin said. “Even if Russia does not take the opportunity to participate in the Artemis program, that does not necessarily mean that our craft should not be adapted to dock with each other.”

In a tweet Monday, Rogozin wrote: “The plans of Russia and China on the moon are open to broad international participation. This is not about confrontation, but about cooperation in the exploration of the moon.”

Mark Kirasich, NASA’s deputy associate administrator for advanced exploration systems, said last month that the U.S. space agency will continue working with Russia on technical standards to ensure U.S. and Russian spacecraft will be capable of docking in space.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.