On its second test flight Tuesday, Astra’s privately-developed small satellite launcher ran out of fuel seconds before reaching the velocity needed to enter orbit but exceeded the company’s expectations with an otherwise-successful climb into space from Kodiak Island, Alaska.

Astra officials said Tuesday the rocket “performed flawlessly” for roughly eight minutes, successfully demonstrating the launcher’s first stage burn, stage separation, payload fairing jettison, and second stage ignition milestones on the ascent into space.

The second stage engine shut down prematurely after exhausting its kerosene fuel supply, leaving the rocket just shy of the velocity required to reach orbit around Earth, Astra said.

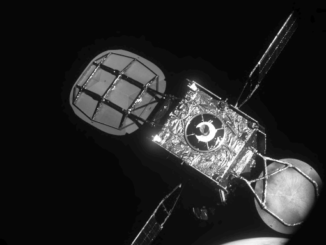

Astra shared images captured by the rocket after it reached space, showing the curvature of the Earth and scattered clouds hanging over the deep blue Pacific Ocean. The company said the rocket flew to a maximum altitude of about 242 miles, or 390 kilometers, and reached a top speed of around 16,100 mph (7.2 kilometers per second).

“This far exceeded our team’s expectations,” said Chris Kemp, co-founder and CEO of Astra, based in Alameda, California.

If the second stage engine had fired its full duration — just 12 to 15 seconds longer, Kemp said — the rocket would have gained another 1,000 mph in velocity and entered a stable orbit, according to Astra.

Astra says the second stage’s early cutoff can be fixed with a tweak to the upper stage Aether engine’s propellant mixture ratio, which governs how much kerosene fuel it consumes relative to liquid oxygen, the rocket’s oxidizer.

“We now have flight data, so we can tune the mixture between the fuel and the liquid oxygen, so there’s no residual liquid oxygen in the next flight,” Kemp said. “So this system works … From all the preliminary data we’ve looked at, the system performed flawlessly.”

The upper stage engine shut down in a controlled fashion after depleting its fuel, and had the mixture ratio been correct, the rocket would have reached orbit, Kemp said.

A quick video recap of our 8.5-minute flight to space today! pic.twitter.com/gvElF4fbAZ

— Astra (@Astra) December 16, 2020

Astra’s Rocket 3.2 vehicle — the company’s second rocket to attempt an orbital flight — took off from the Pacific Spaceport Complex at Kodiak Island, Alaska, at 3:55 p.m. EST (11:55 a.m. Alaska time; 2055 GMT) Tuesday.

Five kerosene-fueled Delphin engines, developed in-house at Astra, powered the 38-foot-tall (11.6-meter) rocket through a blanket of clouds with 32,500 pounds of thrust.

Astra set measured objectives for the test flight, the second of three demonstration launches the company has said it expected to need to reach orbit.

The first stage’s five engines fired for 2 minutes, 22 seconds, and the rocket jettisoned its clamshell-like payload fairing three seconds later. The stages separated next, followed by ignition of the second stage engine 2 minutes, 33 seconds, into the flight.

“This is where I believe most of the team would have called it a day and felt we had a very successful flight because it would have meant that the first stage of the rocket was ‘de-risked’ and we could turn all of our attention of our third and final flight to the upper stage,” Kemp said. “But the rocket continued to perform.”

After shutting down its upper stage engine, the rocket simulated procedures to deploy a payload into space. There were no satellites aboard the test flight Tuesday, and the rocket re-entered the atmosphere and burned up.

Engineers will analyze data from Tuesday’s flight over the coming weeks, but Kemp said Astra is on pace to perform its next launch — with Rocket 3.3 — from Alaska in early 2021. He added that Astra does not expect to change any hardware or software code on the next rocket, but can resolve the mixture ratio problem with adjustments in software parameters.

“We expected to have a really successful first stage flight and have something go wrong with the second stage, to be honest with you,” Kemp said in a conference call with reporters Tuesday. “We now have some tuning to do and another rocket ready to go here at Astra — Rocket 3.3 — and we are intending to put a payload on this rocket and fly it.”

Kemp said Astra’s approach to rocket development — using rapid design cycles and a series of test flights — has proven successful with the better-than-expected outcome of Tuesday’s launch.

“There are some things that we can’t test on the ground, and (one) is an optimization of the mixture control ratio on the upper stage,” Kemp said. “It’s only something that you can test in flight. So we got the data we need to make the optimizations necessary to get that mixture control ratio correct on the next flight.

“That’s great news from our perspective,” Kemp said. “It proves our why iterating and getting to space sooner is the better approach.”

Astra was established in 2016 to mass-produce rockets at relatively low cost, giving military, government, and commercial customers a more affordable option to launch small satellites. Its competitors in the small satellite launch market include Rocket Lab, which has been in commercial service for several years, and Virgin Orbit, which plans its second orbital launch attempt in January after its air-dropped rocket failed just after engine ignition on its inaugural test flight in May.

Numerous other companies, such as Firefly Aerospace and Relativity Space, plan to launch their small satellite launchers for the first time in the next couple of years.

“This today demonstrates that this is the right strategy for space: iterating, learning as quickly as possible, incorporating the learnings into the next release, and iterating quickly,” Kemp said Tuesday. “So we intend to continue to iterate with Rocket 3.3, 3.4, 3.5, and beyond, increasing performance, decreasing cost and ultimately delivering our customers’ payloads to space at a fraction of the cost that has ever been accomplished before.”

Astra’s first orbital launch attempt Sept. 11 ended 30 seconds after takeoff when a guidance system problem caused the rocket to drift off course. In response, the rocket’s engines were commanded to shut down and the vehicle fell back to the spaceport on Kodiak Island.

The company says its rocket and the vehicle’s ground infrastructure can be shipped to launch sites around the world and set up in a few days with small team. At Kodiak, Astra’s launch site is a bare concrete pad before the company’s hardware begins arriving before each flight.

A crew of five set up the mobile launch pad and Rocket 3.2 at Kodiak over several days, Kemp said, but Astra had to send a backup team to finish the job after a member of the primary crew tested positive for COVID-19. That forced the first team to quarantine in their hotel.

“I think this a huge testament to the automation, the refinement, that has gone into this system over the past couple of years since we first started building and launching orbital rockets, that we are now at a point that just five people can go up and set up the entire launch system, launch site, and rocket, and launch it in just a couple of days,” Kemp said.

A control team working from Astra’s headquarters in California oversees the final launch countdown.

Astra currently has around 100 employees, and the company says it has raised $100 million to date from private investors. Buying the full capacity on a launch of an Astra rocket will cost about $2.5 million, the company says, less than the price of a dedicated flight on any other orbital-class rocket.

Kemp declined to give a number on the amount of payload mass Rocket 3.2 could have delivered to orbit, but Astra officials said earlier this year that Rocket 3.1 — which launched in September — was designed to carry up to 55 pounds (25 kilograms) of cargo into orbit.

Astra says it has a roadmap for more capable rockets, eventually aiming to build a launch vehicle to deploy a satellite with a mass up to 330 pounds (150 kilograms).

“At some point, we will make some number of identical copies of this rocket,” Kemp said. “And I think that’ll come in the next six months or so, where we really just turn production on and we make a dozen or so identical carbon copies of the same rocket.

“We continue to have a roadmap ahead of us where ultimately, over the next couple of years, we are going to continue to increase the performance and decrease the cost of the rocket, where we’re able to fly large numbers of small satellites very competitively with larger rockets.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.