Members of NASA’s independent panel of aerospace safety advisors raised concerns last week about quality control problems that “seemingly have plagued” Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule program, while urging NASA to closely monitor SpaceX’s plans to reuse Crew Dragon spaceships on astronaut flights to the International Space Station.

An unpiloted test flight of Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft in December ended prematurely after a programming error in the capsule’s mission elapsed timer caused the ship to burn too much fuel shortly after separating from its Atlas 5 rocket.

The unexpected fuel consumption left the Starliner capsule with insufficient propellant to complete its flight to the space station.

The Starliner landed safely in New Mexico two days later, but ground teams identified another software problem in a propulsion controller governing thrusters on the spacecraft’s service module, which jettisons from the Starliner crew module before re-entry into the atmosphere. Mission control uplinked a software patch shortly before re-entry, eliminating a risk that the mis-configured propulsion controller could have caused the jettisoned service module to ram into the crew module after separation.

There were also problems with the Starliner’s communications system during the unpiloted demonstration mission, known as the Orbital Flight Test, or OFT.

An independent review team that investigated the problems during the OFT mission issued 80 recommendations for Boeing and NASA engineers to address software issues, the communications problem, and management oversight shortfalls in oversight that contributed to the problems on last year’s test flight.

Donald McErlean, a seasoned aerospace industry consultant and member of NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel, said July 23 that Boeing is making progress toward resolving the technical problems. Boeing plans to fly a second, previously-unplanned Starliner Orbital Flight Test to the space station late this year, followed by a Crew Flight Test in the first half of 2021 with a three-person team of astronauts on-board.

“However, despite this progress, which is definite and in fact measurable, the panel continues to be concerned about quality control problems that seemingly have plagued the Boeing commercial crew program,” said McErlean, a former chief engineer for the U.S. Navy’s aviation programs.

Boeing performed a pad abort test of a Starliner crew capsule last November, the month before the Orbital Flight Test. One of the capsule’s three main parachutes did not deploy after an otherwise-successful test of the spacecraft’s abort engines, and Boeing traced that problem to a missing pin in the parachute’s rigging.

“We realize that the CCP (Commercial Crew Program) has been working with the safety and engineering communities to address these issues, but this is still an issue that the panel will continue to watch closely as OFT and later CFT are conducted,” McErlean said.

The panel recommended NASA’s Commercial Crew Program “maintain a balance” between setting and achieving schedule milestones and ensuring managers make appropriate technical decisions, according to McErlean.

Boeing developed the Starliner spacecraft under contract to NASA, which is seeking to end its sole reliance on Russian Soyuz crew capsules to ferry astronauts to and from the space station. NASA awarded Boeing a $4.2 billion contract and SpaceX received a $2.6 billion deal in 2014 to complete development of the Starliner and Crew Dragon spaceships.

The public-private partnerships were designed to end U.S. reliance on Russian Soyuz spacecraft for crew transportation to and from the space station.

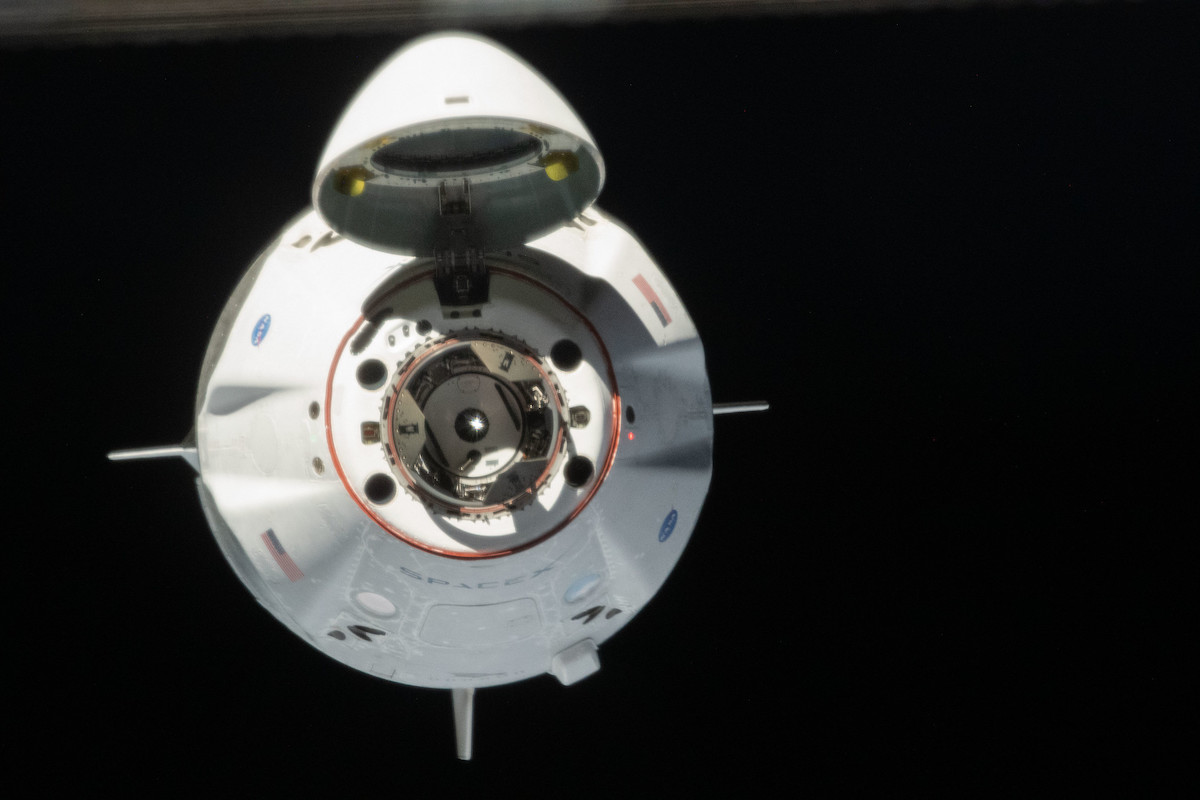

While Boeing still has at least two Starliner test flights — one without crew members and one with astronauts — before the capsule is declared operational, SpaceX is nearing the end of the Crew Dragon development program. The human-rated capsule launched with astronauts for the first time May 30 on the Demo-2 mission, and delivered NASA test pilots Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken to the International Space Station the next day.

Hurley and Behnken are scheduled to depart the station Aug. 1 and splash down off the Florida coast Aug. 2, completing a mission spanning more than two months. Once the Crew Dragon is back on Earth, SpaceX and NASA engineers plan to formally certify the SpaceX crew capsule for regular crew rotation missions to the space station, beginning with a launch as soon as late September from the Kennedy Space Center carrying four astronauts to the orbiting research complex for a six-month expedition.

The mission scheduled for launch in late September — known as Crew-1 — will be followed by at least five more operational Crew Dragon missions through 2024.

NASA last month said it will allow SpaceX to reuse Crew Dragon spacecraft and Falcon 9 boosters for NASA astronaut missions. NASA says SpaceX could begin reusing Crew Dragon vehicles and Falcon 9 first stages on crewed launches beginning with the second post-certification mission, or Crew-2.

The Crew-2 launch is scheduled in February 2021. The Crew-1 mission — SpaceX’s first operational astronaut flight — is slated to fly with a brand new Crew Dragon spacecraft and Falcon 9 rocket.

Each of SpaceX’s operational crew rotation flights to the space station will carry up to four astronauts, including space fliers from NASA and the space station’s international partners.

NASA has assigned astronauts Mike Hopkins, Victor Glover and Shannon Walker to the Crew-1 mission. Japanese astronaut Soichi Noguchi will join the U.S. astronauts on the Crew Dragon spacecraft.

“You are seeing the beginning of the rotational use of the commercial crew systems in transporting our astronauts to the ISS,” McErlean said.

In the safety panel’s July 23 public meeting, McErlean said SpaceX currently plans to refurbish and reuse the Crew Dragon spacecraft that is flying on the Demo-2 mission on the Crew-2 mission next year. That crew capsule was named Dragon Endeavour by Hurley and Behnken soon after their launch in May.

SpaceX also aims to reuse the Falcon 9 rocket booster assigned to the Crew-1 mission again on the Crew-2 launch next year, McErlean said.

“So in this case, Crew-2 will be fully utilizing the SpaceX reuse philosophy,” McErlean said. “Although reuse has been successful in prior launches, the use of previously-flown hardware for a human spaceflight mission is unique, and it will create some additional work for NASA, who must address the human certification requirements.”

Boeing also plans to reuse Starliner crew capsules on multiple flights. Unlike the Crew Dragon, which splashes down at sea, the Starliner parachutes to an airbag-cushioned touchdown on land.

McErlean, speaking for the safety advisory panel, said NASA must also keep up with SpaceX’s philosophy of “constantly evolving vehicle designs” with an “ongoing formal safety-related process” to ensure the modifications remain within the agency’s human-rating certification requirements.

“With the completion of the Demo-2 mission and appropriate vehicle changes driven by the data gathered during that mission, NASA will have a essentially concluded the required certification process for flying NASA personnel on SpaceX hardware,” McErlean said. “However, it is the panel’s opinion that given the SpaceX approach to hardware upgrades, NASA has to decide by what processes it will continue to monitor vehicle and system changes to ensure that those changes still remain within an appropriately certified safety posture for human spaceflight operations.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.