NASA is modifying plans to send astronauts back to the moon in 2024 by taking the Gateway — a mini-space station to be assembled in lunar orbit — out of the critical path in favor of a simplified architecture, according to the agency’s chief of human spaceflight.

Doug Loverro, who took over as head of NASA’s human spaceflight directorate last year, said Friday the agency is seeking to minimize risks in achieving the schedule for a 2024 moon landing set by the Trump administration last year. NASA was previously aiming to return astronauts to the lunar surface in 2028.

While Loverro said NASA is “anxious” to build a lasting, sustainable human presence at the moon, the accelerated schedule required agency officials to be more “scrupulous” in their planning.

“If it’s not mandatory, it’s not necessary,” Loverro said Friday in a meeting of the NASA Advisory Council’s science committee. “How do we go ahead and eliminate risk? How do we go ahead and burn down risk? How do we make sure we decouple sustainability and speed? How do we do all of those things, and then what does the program look like?

“And I have to tell you it doesn’t look like the program that we were trying to make happen before I got here,” Loverro said. “That’s not a dig on anybody who was here beforehand. That’s a stark recognition that when our (objective) was moved from 2028 to 2024, we were not as precise and careful to re-look at all of our plans with those colored glasses in mind to say we have got to change things, even though we’ve been planning on something for a long time. To truly get the new objectives done, things have got to change.”

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine named Loverro, an experienced manager of national security space programs, as head of the space agency’s human exploration and operations directorate in October. Loverro replaced Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA’s longtime human spaceflight chief who Bridenstine removed from the position last July.

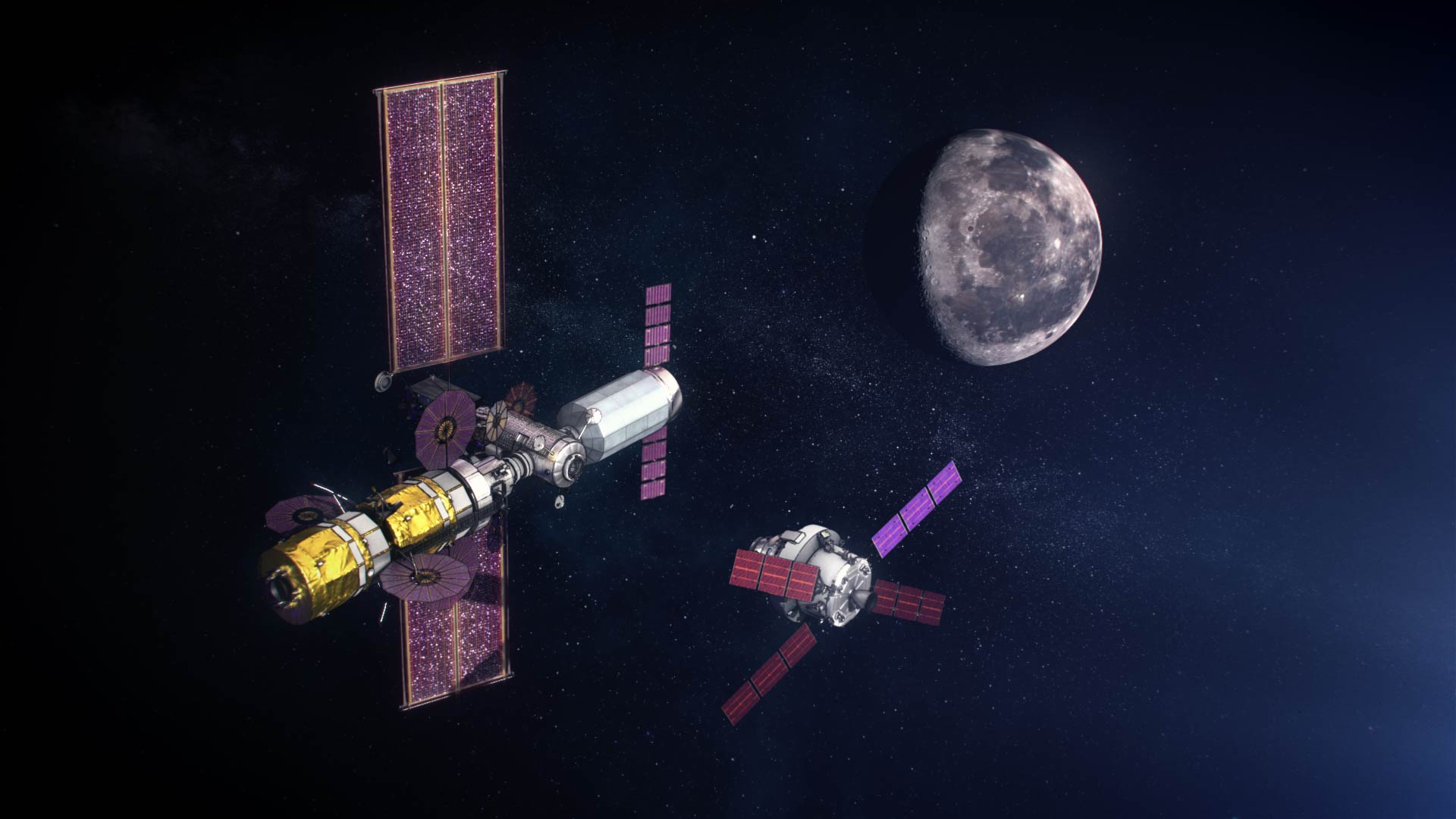

One of the changes Loverro has made is to take the Gateway out of the critical path for the 2024 moon landing, a central goal of NASA’s Artemis program.

NASA formulated plans for the Gateway before Vice President Mike Pence announced the 2024 moon landing schedule last March. Loverro said the Gateway remains important for developing a sustainable lunar exploration program, with a series of crewed missions to the moon’s surface, accompanied by robotic landers and cargo deliveries.

With the new schedule, NASA has four-and-a-half years to develop a human-rated lunar lander. In the Apollo program, it took six-and-a-half years from the time NASA signed the lunar lander contract until the Apollo 11 landing in July 1969, Loverro said.

“So a lot of what we’re doing is trying to look at what are all the risks that can get in our way in our four-and-a-half-year schedule, and how do we go ahead and pull them all early in the program, or eliminate them from the program altogether, by going ahead and making wise technical and programmatic choices,” Loverro said.

One of those risks involves the Gateway, he said.

“By taking Gateway out of the critical path for a lunar landing in ’24, I believe what we have done is create a far batter Gateway program out of it,” Loverro said.

Space agencies in Europe, Canada, Japan and Russia have proposed elements to join the Gateway, which will be assembled in an elliptical, or egg-shaped, orbit around the moon.

NASA’s most recent schedule for building the Gateway called for a launching the facility’s power and propulsion module, to be built by Maxar Technologies, on a commercial launch vehicle at the end of 2022.

A pressurized habitation element built by Northrop Grumman would launch on another commercial rocket in late 2023, giving the Gateway a minimal capability to host astronauts on the Artemis 3 mission on the way to the lunar surface. Elements of a commercially-built lunar lander would launch on multiple rockets in 2024 for robotic assembly at the Gateway, followed by the arrival of the Artemis 3 crew on an Orion spacecraft.

The piloted Orion capsule is designed to launch on top of NASA’s Space Launch System, a heavy-lift rocket scheduled to launch next year on a test flight without astronauts. Another SLS/Orion launch in 2023 would carry astronauts around the moon and back to Earth on the Artemis 2 mission, setting the stage for a lunar landing attempt on the Artemis 3 flight in 2024.

Contributions from international partners, such as a Canadian robotic arm and a European communications and refueling module, would not arrive at the Gateway until after the 2024 moon landing attempt.

“I will share with you that one of the critical portions of Gateway is the international cooperation that we have in Gateway,” Loverro said Friday. “Come Monday, I will tell them we have made that decision to take that out of the critical path. Many of them were worried … Does that mean that you’re not committed to Gateway? The answer is absolutely, positively no. We are committed to Gateway.”

Loverro said the decision will ensure that any delays on the Gateway program do not impact the 2024 moon landing schedule.

He said the Gateway has a “high possibility” of delays, citing challenges developing an advanced high-power solar electric propulsion system for the Gateway’s power and propulsion element.

“From a physics perspective, I can guarantee you we do not need it (Gateway) for this launch,” Loverro said.

He added that “decoupling” the Gateway from Artemis 3 schedule will “shore up” the program because NASA managers will not be forced to remove technologies and capabilities from the orbiting lunar station to keep it on track to support a 2024 moon landing.

“If it (Gateway) gets behind schedule, no problem,” Loverro said. “You can still maintain it being there. All of my international partners were dependent on it being there by 2026. Not a single international partner was ready to do anything on Gateway until 2026, so we now can tell them 100 percent, positively, it will be there because we’ve changed that program to a much more what I would call a stolid accomplishable schedule.”

Loverro later said that NASA is making changes to the Gateway program to reduce its costs, helping ensure the Gateway does not compete for limited funding with the agency’s drive to develop a human-rated lunar lander.

“Frankly, had we not done that simplification, I was going to have to cancel Gateway because I couldn’t afford it,” he said. “But by simplifying it and taking it out of the critical path, I can now keep it on track.”

In his discussion Friday with members of the NASA Advisory Council science committee, Loverro stressed several times that NASA remains committed to the Gateway.

“I do fundamentally believe you cannot do sustainable presence on the moon without Gateway,” he said. “You need an assembly point in the low gravity well of a near rectilinear halo orbit. You need an assembly place to go ahead and bring down the equipment that will be necessary for extended lunar durations.

“So there’s no question that Gateway is part of that plan, and I think what we’re doing with Gateway makes sure that it does not get threatened by future cuts — or future budget overruns, more likely — on human landers, or Space Launch Systems, and Orion capsules, and those kind of things,” Loverro said.

Loverro also suggested that NASA may also change the architecture for the Artemis program’s lunar lander development.

“Program risk is driven by which things you haven’t done in space before that you cool have to do in this mission,” he said.

Last year, NASA requested proposals from industry to develop a commercial lunar lander. The space agency envisioned a lander with two or three elements — such as an ascent module, a descent platform and a propulsive transfer section — that could be launched separately on commercial rockets into orbit around the moon.

The elements of the lander could dock together in lunar orbit, perhaps at the Gateway, to await arrival of the Artemis 3 crew on the Orion capsule.

Blue Origin, Boeing and Dynetics have confirmed they proposed human-rated lunar lander concepts to NASA. SpaceX is also widely believed to have submitted a proposal, although the company has not confirmed it.

Blue Origin’s lunar lander would come in three pieces: A descent module built by Blue Origin, an ascent stage provided by Lockheed Martin, and a transfer element from Northrop Grumman.

In contrast, Boeing proposed a fully integrated lander that could launch on NASA’s Space Launch System. Boeing is also prime contractor for the SLS core stage.

Loverro said Friday that NASA is seeking to minimize technical and programmatic risks to achieve a crewed moon landing in 2024. He cited as a programmatic risk NASA’s plans to launch the pieces of a lunar lander on separate rockets to meet up at the moon.

“We’ve never done that before, so we would like to try to avoid doing things we’ve never done before,” he said.

“Basically, of 34 critical operations that are necessary to get to the moon, about 25 of them have never happened until the final mission Artemis 3 gets to the moon,” Loverro said of NASA’s current Artemis plan. “That makes no sense. You should be able to go ahead and that take that risk out by looking at some of those critical operations and making them happen earlier in the program, in some of your test program.”

When Loverro took over NASA’s human spaceflight directorate last year, Bridenstine charged him to review the agency’s Artemis program, including the schedules for major missions.

Loverro said Friday that details of the new plan will be revealed in the “near future.”

“We will obviously roll out that plan when we have it all locked into stone in the budget and in policy,” Loverro said.

Although changes to other parts of the Artemis program appear imminent, Loverro said the Space Launch System — a rocket already more than two years behind schedule and billions of dollars over budget — remains “mandatory” to achieve a crewed lunar landing in 2024.

“The Orion spacecraft is 27 metric tons with the service module … The only existing launch vehicle that it can get to translunar injection on is an SLS,” Loverro said. “I know. I’ve run the numbers on every other existing launch vehicle. I’ve had people do the analysis of where can I put it in orbit, how can I get things done? There is just no way to get to the moon without SLS.

“I know that’s going to be the case from now through 2024 because we’ve looked at all of the schedules of all the other rockets that people are trying to develop. And in my mind, it’s likely to be the case at least through most of this decade.”

Loverro said the U.S. commercial launch industry is “incredibly robust and is going to produce things that are going to go ahead and water all of our eyes, just the way SpaceX does every time they land a booster.”

He did not mention SpaceX’s Starship vehicle, which the company is designing to carry heavy cargo and people into orbit, and eventually to the moon, Mars and other deep space destinations.

“I want to help those folks succeed, but I don’t know any way I can do the mission I’ve been asked to do right now without SLS or a transporter … So I’m stuck with SLS,” Loverro said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.